Published Posts

Top 5 Things Local Historians Are Getting Wrong

We've identified a short list of issues with doing local history, from trivia peddling, nostalgia pimping, permitting undocumented history, fixated obsessions with the past, and aversions to digital media. We also weigh in on local history musems' provincialism, poverty mindset, and feigning interest in serious oral history work.

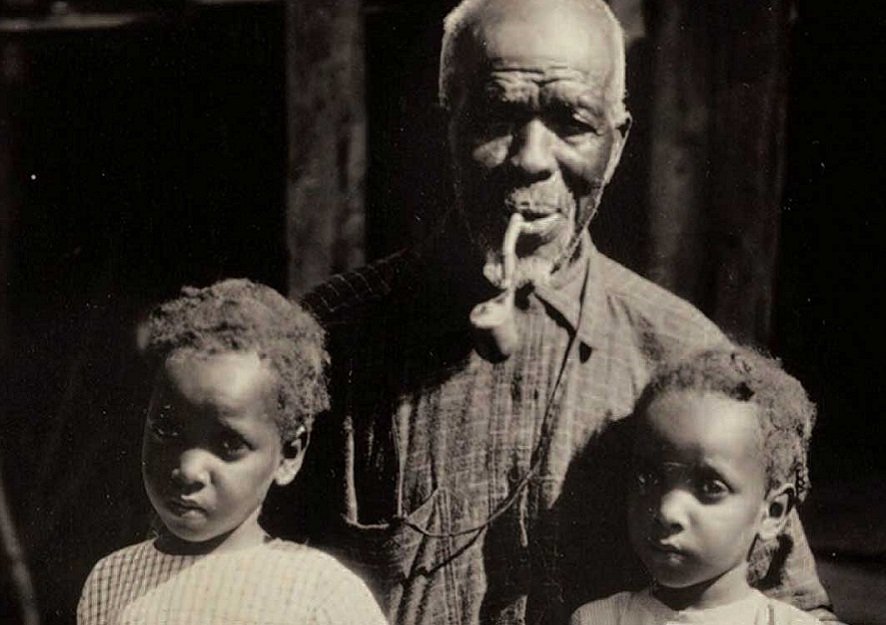

Put Your Foot In It: Beaver County Black History

The silence of Beaver County Black local history is deafening. That may be an exaggeration to some, after all, our pantheon of historical figures recognizes such Black notables as James Howard Bruien, Lem Dawson, Betty Mathers, Richard Woodson, William Patrick Ormes, Paul Short, Calvin Smith, William Neal Brown, Willis Sanderlin, Rosa Alford, Harry, L. Garrett, Dr. James Frank, William Alston, George “Tookie” James, and George Walker. [click image to read more]

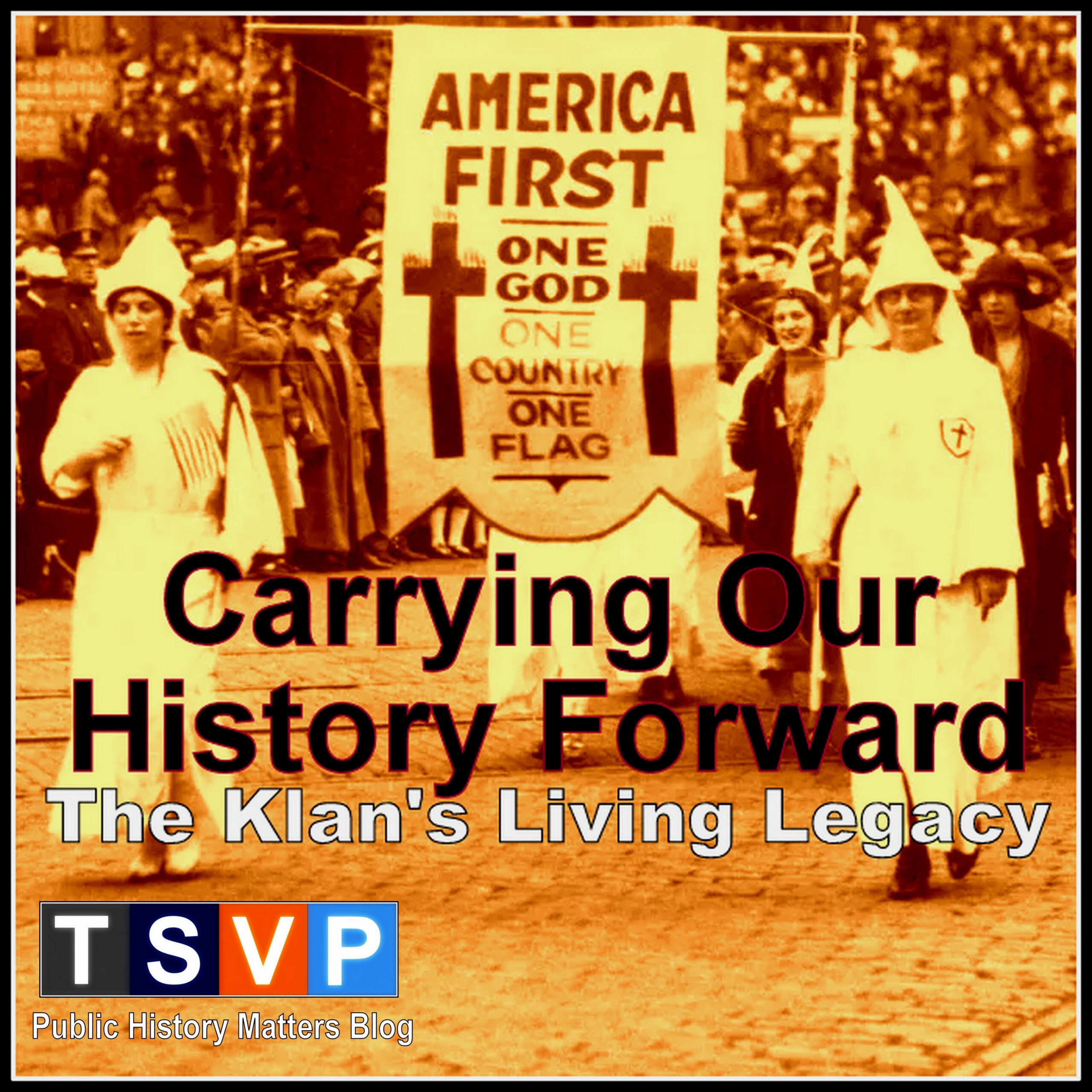

Carrying Our History Forward: The Klan’s Living Legacy

We are trying to understand the history and legacy of the Ku Klux Klan in Beaver County, Pennsylvania, especially after its organizational heyday in the 1920s. Local organizations (Klaverns) may have disbanded after the 1920s, but the Klan’s fundamental ideology, values, and attitudes toward society, race, immigration, religion, patriotism, and many other issues are living on, simmering in what we call the legacy years. In this sense, we would argue, the Klan’s original extremist worldview survives to this day in Beaver County, albeit evolved in response to the social, economic, and political conditions of our time. We have not seen hooded rallies, yet, but we have seen renewed expressions promoting well-documented Klan sentiments–as the parade banner above illustrates: America first, one God, one country, and one flag. Like in the 1920s, contemporary messaging champions anti-socialism, freedom from government tyranny, individual liberty, and gun rights. [click image to read more]

Deconstructing Local History: The Curious Case of the Wives’ Club

The original intent of the newspaper story and our photo was most certainly not an expose on gender identification. It was simply local news reporting about a civic organization. But though deconstructing the artifact as we find it, we can formulate a more interesting historical research question, one that we may never have thought of without some effort to critically “read” this artifact and apply a textual analysis–revealing not one single meaning, but rather many often conflicting meanings. [click image to read more]

Plagiarism: Ripping off Local Historians and History

“The expropriation of another author’s work, and the presentation of it as one’s own, constitutes plagiarism and is a serious violation of the ethics of scholarship,” concludes the American Historical Association. “It seriously undermines the credibility of the plagiarist, and can do irreparable harm to a historian’s career.” The concept is simple enough: if you’re an historian you ought not steal from other people’s creative work or creations. Don’t rob another organizations’ archives and pass artifacts off as your own. Don’t steel other people’s historical writings and claim them to be your own words and ideas. But if you do borrow from other sources, at least give credit or attribution to the source preferably using an acceptable method such as the Chicago Manual of Style. [click image to read more]

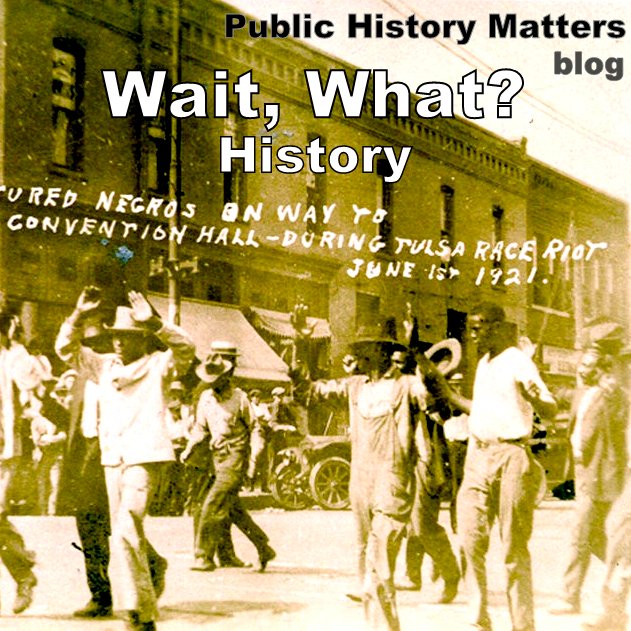

Wait, What? I Never Knew That! Hidden Histories and Mysteries Revealed

Public historians should always anticipate these questions at every turn. The answers (plural), should be intentionally and explicitly taught. In this regard, public historians should take on the role of public educators–especially at the local level where history is most impactful. As such, one of the duties involved should be to seek out and reveal hidden histories such as the Tulsa Race Massacre and to dispel their “mysteries” (in part, why they’ve been hidden) through the use of critical historical thinking. [click image to read more]

Who Owns You? The Need to Document Historical Images

As for historical images posted to social media–where sharing among thousands of people is easily possible–there is a severe risk of old photographs being disconnected from their historical documentation–including information about rightful ownership. A too common belief among the public and far too many untrained historians is that all “old photographs” are in the public domain–free to possess, share, manipulate, watermark, or monetize. This is simply not true. Photographs must be assumed to be private property unless clearly identified and understood as being in the public domain. But how would we know this unless photographs are properly documented? Here in lies another danger of undocumented images. Just because an historical image is widely disseminated and shared on social media does not mean that it is free of any copyright or ownership claims. In fact, a lack of proper historical documentation encourages a false assumption that such images are in the public domain and therefore free to appropriate. [click image to read more]

Historians Bearing Witness to History

description

Going Gentle Into that Good Night: Communities Don’t Let Historic Voices Go Silent

We’ve long advocated that local history museums and historical societies (seems like every small town has one) are uniquely positioned to be oral history centers in their communities. Often run by trained public historians (professional or amateur) deeply interested and knowledgeable about their communities, local history centers are well suited to capture, preserve, and share the life stories (oral histories) within their own communities. And local historians who partner with media and community-focused storytelling efforts such as The Social Voice Project can amplify their capabilities. Oral history work is skilled work, and in our experience-based opinion far too precious to be managed by unskilled amateurs. [click image to read more]

Radio Theater as Public History

For public historians, understanding this fundamental relationship between storytelling and humans gives insight into opening exciting opportunities to bridge the gap between the history inside the museum and the public standing just outside its doors. One way to invite people in is to inform, entertain, and educate them through historical storytelling. [click image to read more]

On This Day, Years Ago: Widening the Lens of Local History

One of the most powerful tools public historians use is a simple question: Do you remember . . .? Of course, we have to frame the question within the scope of contemporary history–that is, within our life time and near-field memory. Simply living through life authorizes us to bear witness to the world around us. If we lived through it, and remember it, and can share a story about it–we can and should include it in the historical record.

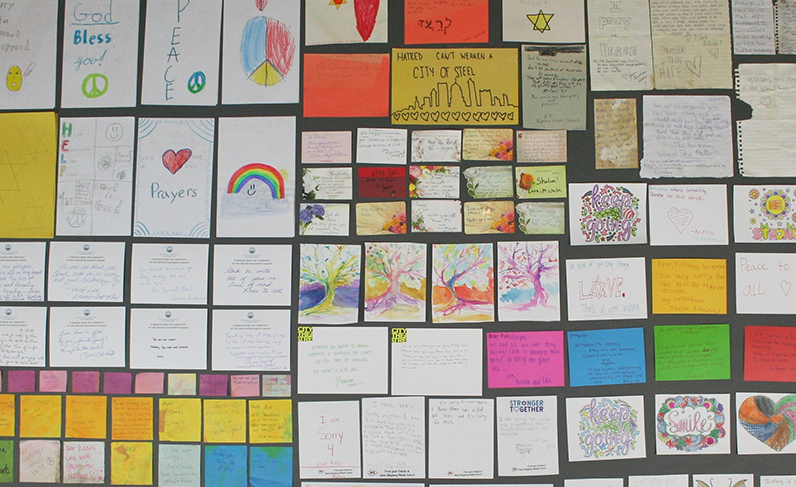

Rapid Response: Do Local History Now

We’ve long advocated for this type of rapid response historical engagement focusing on the present. After all, what happens today will soon enough be in the past. We can’t escape this timeline. Doing contemporary history work (i.e., engaging current events as historical events) is among public historians’ best practices. It demonstrates not only wise forethought and perspicacity, but it also reveals something profound about an organization’s operating philosophy, understanding, and values. [click image to read more]

Local History: The Musical

There’s no reason to believe that the power of transformative theater is only about history’s major events and characters. The art form can also be applied to local history, as is done currently with the Off-Broadway play, Coal Country. [click image to read more]

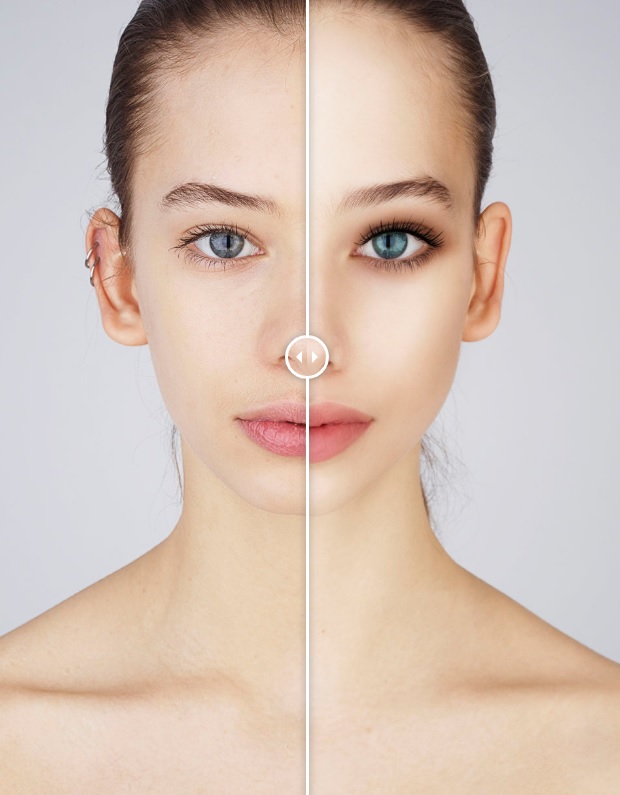

“De-oldifying” History: Creative Interpretations of How Things Might Have Been

As Ted Turner realized, people have strong opinions about “messing” with these old recordings. Overall, we learned how deeply people abide by originalism. Terms such as, corlorized, digitally remastered, restored, or enhanced, or now in HD tend to flags concerns that the original quality has been compromised. And this is sometimes true, especially when older media has been processed in the hands of less skilled technicians. But new renderings of old media are sometimes remarkably well done technically, artistically, and historically. What’s the harm in improving the quality of a film, photograph, or sound recording? This question should be of critical importance to public historians, especially in the age of digital media. [click image to read more]

Watermarking History: Laying Claim to the Public Domain

Any history organization—of any size or budget—with online access can now present their historical photographs to the world. Such abundance of readily accessible local history photographs on the internet is remarkable, and only made available through the democratization of digital media. Moreover, these photographs can be used in exciting new ways to educate, entertain, and inspire the public to take an interest in local history. But legally speaking, many of these local history photo archives contain images that are in the public domain, and anyone may use these images free and clear of any restrictions–including watermarking them and publishing them elsewhere on the internet. But is this ethical? [click image to read more]

Recognizing What Women Done Did: Women’s Roles in History:

Let’s make some attempt to recognize the full spectrum of women’s history, not just the overly exposed highlights that might fit neatly into a 5th grade history book. The history of women as sex workers doesn’t have to be “celebrated,” but it should not be muted either by those who find the topic more unseemly than the historic violence of warfare or the historic vileness of racism and slavery–topics which are typically on full graphic display in museums but presented appropriately and in context by skilled and thoughtful public historians.

Stories of . . . History

Throughout this blog we have strongly promoted people history over artifact history. In other words, a rusted old 19th century coal bucket is self-evident, but it can’t speak for itself. It takes a public historian to tell its story. A Civil War era medical bone saw is impressive hardware behind museum glass, but just looking at its cold steel does little to evoke the blood and horrific screams it induced on the battlefield. It takes a story to draw that out of it. We contend that all artifact have worthwhile background stories, and these are essentially people stories. In this blog post we mentioned the term “human-centered” in reference to doing public history through storytelling–again, we emphasize people history over artifact history. As such, when museums tell the “story of . . .” (whatever it might be) we hope that historical story will start and end with people instead of facts and data. [click image to read more]

Local Historians in Service

Capturing, preserving, and sharing the oral histories of our local first responders would give us all a better understanding of the incredible risks taken and sacrifices made to keep us safe. Such awareness could only add value to their service. But, we have to get to their stories or else they go unheard, unknown, unappreciated. Local historians associated with community historical societies, museums, or working independently as writers or media producers have the necessary historiographic skills and know-how to do this. They live and work in the same communities as our local first responders; in many cases local historians are the friends, neighbors, and relatives of first responders. There’s proximity. [click image to read more]

History in the Making: Doing History Now

too many local history organizations are rear facing and fixated on a static past. We think these organizations can and should actively engage current events as historical events because come tomorrow, sure enough, today will be the past. At The Social Voice Project, we strongly encourage public historians, local museums, and historical societies to engage history in real time by doing history in real time. Carpe diem! [click image to read more]

History Leadership Matters

History organizations (museums, associations, societies, etc.) often cite a lack of resources as the number one barrier preventing them from carrying out their mission. It’s this deficit of money, capable staff, volunteers, physical space, technology, or public support—that leads to the cutting of staff, reduction of hours, limiting of programs, neglect of collections, and failure to reach the public. With respect to leadership, we might also add “lack of leadership” to the list of complaints museums cite among their problems. But as motivational speaker Tony Robbins often says, “It’s not the lack of resources, it’s your lack of resourcefulness that stops you.” [click image to read more]

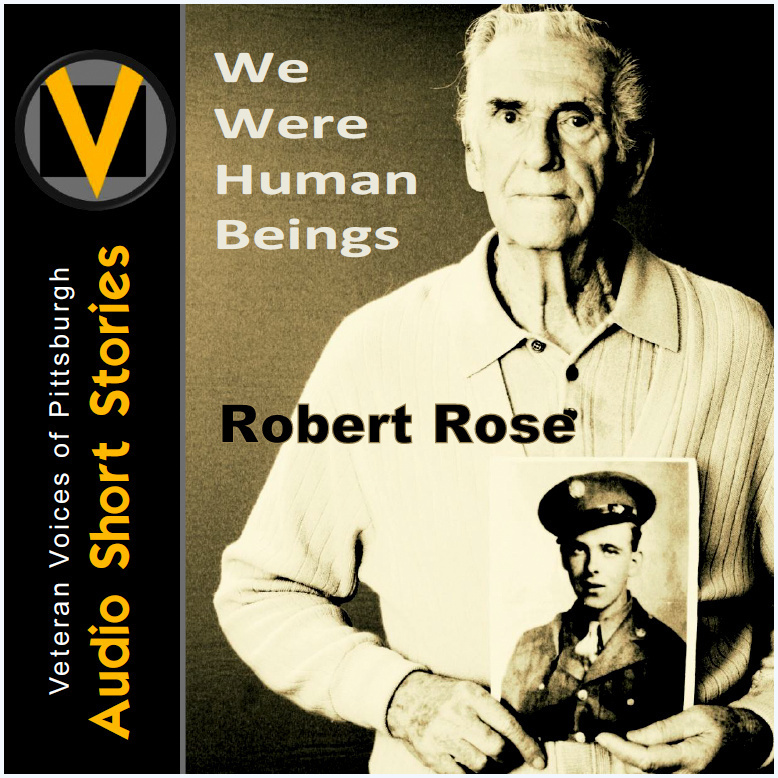

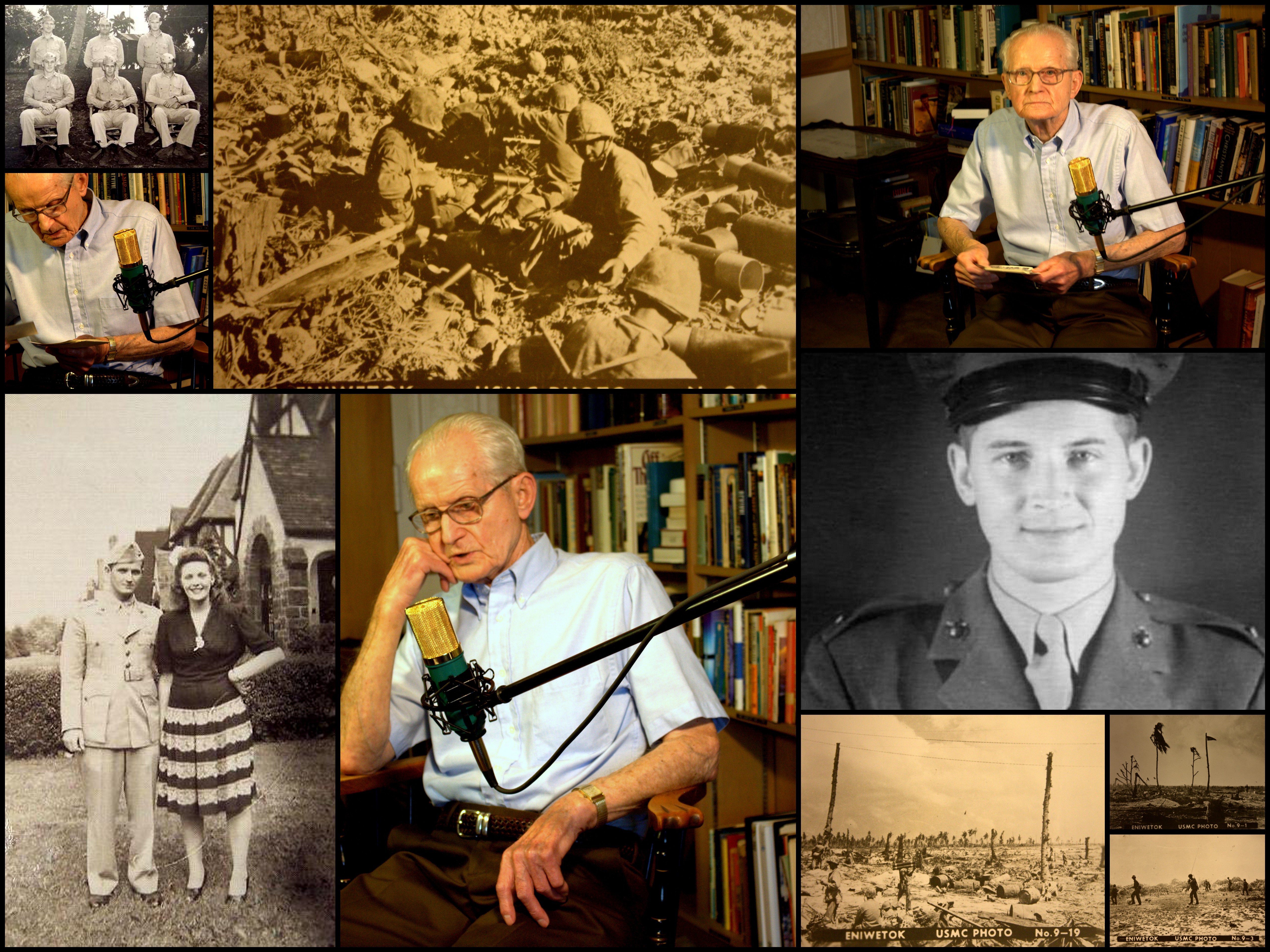

Everyone Has a Story: Veterans Oral History

Let’s face it, it is disingenuous at best for us to say we value the stories of veterans (and others in our community) and proclaim they should be recorded and preserved for history’s sake –yet, we continue to do nothing. In our experience, we rarely get second chances with missed opportunities to record oral history interviews. Unfortunately, as people pass on their voices fall silent; we can no longer hear their stories in their own words. That’s a loss for all of us. [click image to read more] But it doesn’t have to be this way.

Changing Culture, Changing History

The times they are a changing. Without doubt, our social, political, and economic worlds are rapidly transforming themselves fueled by technology, global communications, climate change, and revisions to our social norms. Writ large, we are talking about profound cultural transformations affecting all of us, from small towns to nation states. But culture change is never easy; we struggle with it. Change disrupts our habits and expectations, our traditional ways of thinking and being. Just in the last couple of decades we've started to realize the pressures of profound changes to our world: our global population has exploded with mass urbanization; the internet, phone technology, and social media have changed the way we communicate; our collective security is challenged by organized global terrorism, nationalism, and racism; and climate change is a grim reality. [click image to read more]

More Fun at the Museum

According to Dilenschneidero and the American Alliance of Museums, nearly 865 million people visit museums each year (that’s 2.3 million visits per day) wanting and searching for the experiences she lists above. As public historians, our job is to think about the reasons our museums attract the public, and once they walk through our doors, how we can turn their visit into an experience they will value and remember. Although it’s implied, there is another reason people should come to museums that should be made explicit: People want to have fun. As Dr. Seuss said, “If you never did you should. These things are fun, and fun is good.” [click image to read more]

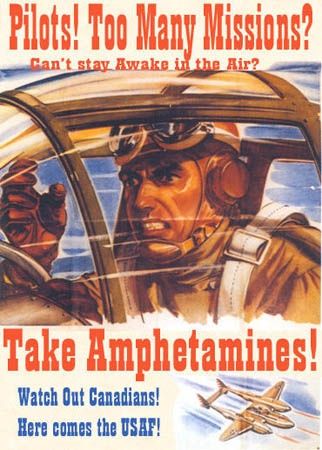

Hopped Up History: The Use of Amphetamines During WWII

Drug use by troops in warfare actually happened (is happening); the phenomenon is real, factual, and historically significant. Yet, this history is mostly unknown. Why is this history squelched from most WWII museums, exhibits, and historical programs? We should ask public historians about this; it might open up an important dialogue about the why and how certain histories are privileged over others, and what are the consequences for all of us. [click image to read more]

You Call That Real Food? Thoughts on food heritage for public historians

When attempting to understand cuisine as an important component of culture, history, and heritage, it pays to use discretion. Not all food is authentic, genuine, or historically significant. (On the other hand, maybe all that matters is that people like Boston Texas BBQ). The topic of food is a minefield of opinions. There's no accounting for taste, the Romans would say, it makes no sense to argue over food. I like tomatoes and you like artificially colored high fructose sweetened tomato celluloid concentrate puree. De gustibus non est disputandum. [click image to read more]

Artifacts help tell history’s story, not the other way around

museums tend to be object-centered, giving less attention to interpretation and meaning of artifacts (i.e., their stories). This is especially true in local history settings, where artifacts are typically left to speak for themselves in display cases, contextualized only through brief placards or identification tags affixed nearby. We contend that artifacts never speak for themselves, therefore it is up to public historians to make more of an effort to frame historical objects within historical narratives–not just of time and place, but also accounting for social, economic, and political themes that continue to shape these narratives–past, present, and future. Artifacts help tell history’s story, not the other way around. Finding the Clotilde reminds us that there’s a story behind every artifact. Public historians need to tell these stories in new and interesting ways because we need to hear them.

History Laws

And let’s remember that local history is easily conditioned; communities and local governments make decisions about which versions of history will prevail based on understandings of history, motivated interests, social and religious values, moral appropriateness, and standards of public decency. And of course, histories that prevail are often those that are made public through the generous support of benefactors and patrons. Public history is usually shaped by the (sometimes unseen) hand of moneyed interests and underwriters. [click image to read more]

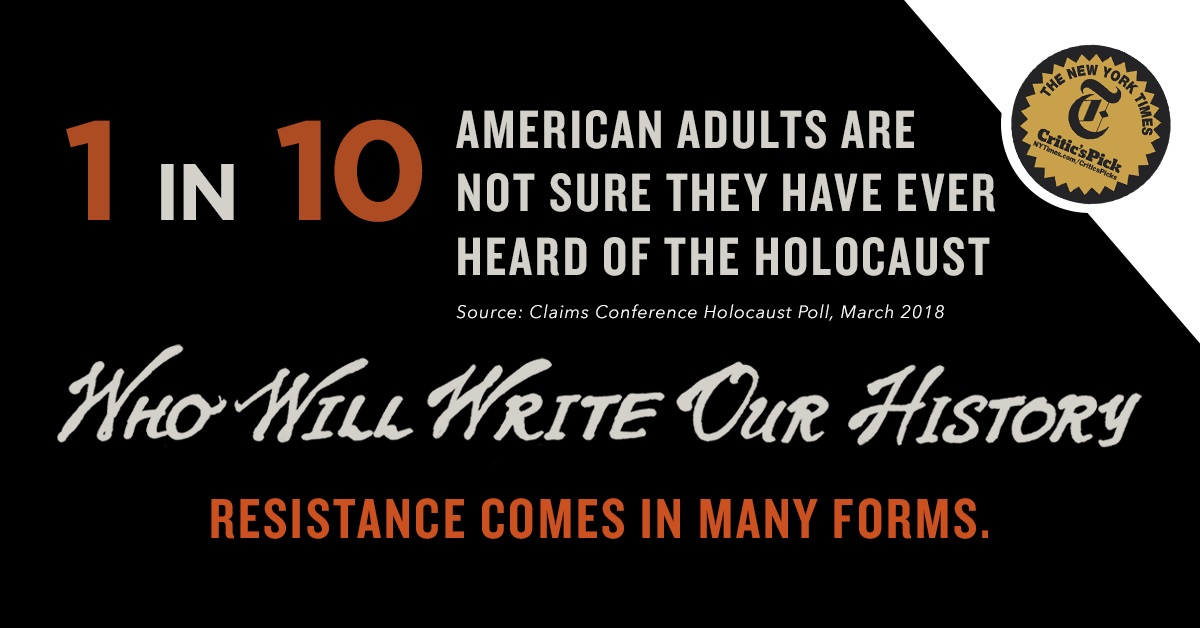

Who Will Write Our History

“The stories a society tells about itself,” writes noted educational theorist Henry Giroux, “are a measure of how it values itself.” When it comes to history, Giroux contends, “America has become amnesiac, a country in which forms of historical, political, and moral forgetting are not only willfully practiced but celebrated.” [click image to read more]

Who's Photographing Beaver County History . . . Today?

Indeed, historical photographs are perhaps museums’ most abundant artifact. And there’s a reason. Since the 19th century, photographers—even in the smallest of towns—have been actively capturing, preserving, and sharing images of daily life, social activities, and news events. Starting in earnest during the early years of the 20th century, photography became ubiquitous, despite the relatively rare, expensive technology and skills necessary to be a photographer. [click image to read more]

Oral History in the Age of Digital Storytelling

Indeed, most oral history interviews do appear clinical, nothing more than unexciting catalogs of facts with as much appeal as corporate training films. Informational? Yes. Interesting? No. Media metrics from our own oral history archive show that audience engagement and interest in traditional interviews is usually very low. And that’s a problem, because a story not heard (or watched) is a story not told. Public historians, those charged with the challenges of educating, entertaining, and inspiring the public around such things as oral history interviews, have begun to take note of what digital storytellers like Chris Padgett are able to achieve by refocusing the form and shape of oral histories. One goal, of course, is to to improve the “sharing” experience with the public. [click image to read more]

So What About History

It’s the shortest question, and yet the hardest to answer. It challenges public historians in ways that put their knowledge, competence, credibility, and authority on the line. So What? It’s a fair question, of course, but it can unsettle us. Behind these words is subtext: I don’t care. I’m not interested. This is irrelevant. For public historians, responding to the “so what” question in meaningful ways is a prime directive and one of the key imperatives of public history: to educate, to entertain, and to inspire. Like it or not, we must now add: to explain why anyone should give a rat’s ass about this old stuff. [click image to read more]

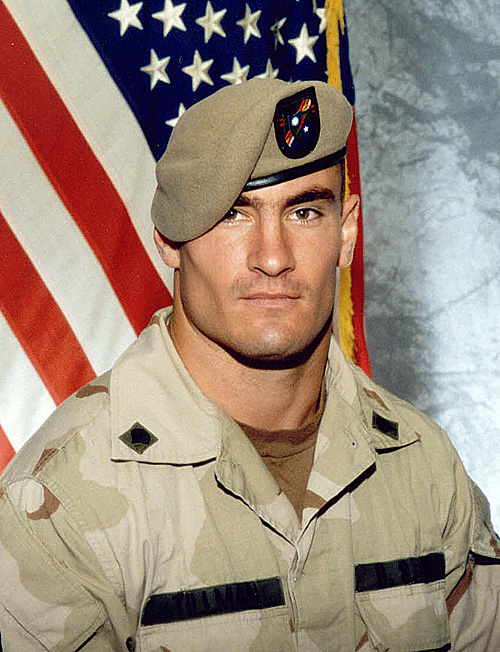

The Legend of Pat Tillman: Historians and Propaganda

But the story they told about Pat Tillman’s death was knowingly false and fabricated. As facts about the incident eventually emerged, the official story of Pat Tillman’s death became scandalous. Even Tillman’s own family now recognizes it as pro-war propaganda. Clearly, Pat Tillman reminds us that the intersection of myth, history, and legend is a complicated and confounding space where facts and fiction sometimes coexist, each bleeding through at various times revealing something different. The Pat Tillman story continues to evolve with each new telling. As time goes on, which Pat Tillman story will endure? And which story will public historians favor? [click image to read more]

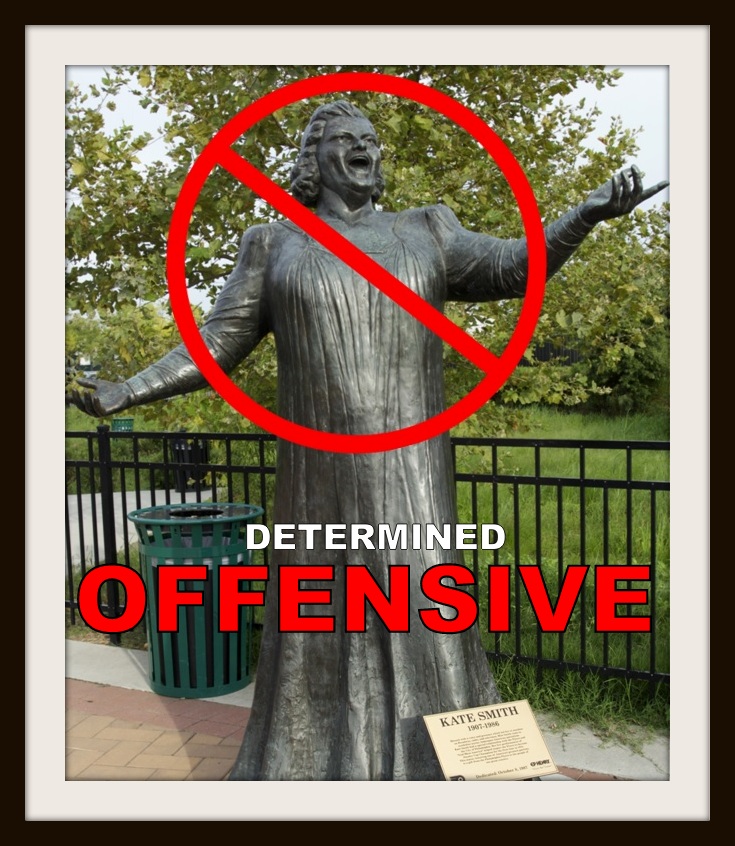

Which History to Honor?

we think public history—such as the figures we choose to honor, exalt, and represent us in the National Statuary Hall or the community park—is always open to reasoned debate and the possibility of principled revision. Of course, we do not get to choose history’s diverse cast of characters— including American scoundrels and saints, patriots and traitors—but we do get to choose which historical figures we want to honor and place on pedestals, representing our shared values and ideals. [click image to read more]

Historical Hero Worship

Most people want to learn the truth about history, even if it rattles common sense or deflates comfortable–but dubious–accounts of history. We recently posted a provocative mini-essay about a particular populist conception of WWII veterans–that they were all heroes. Of course, many were. Some, if we are to be truthful with ourselves, were not. During WWII, one third of all criminal court cases in the entire US were military courts-martial. That’s 1.7 million cases trying WWII GIs for criminal conduct. In fact, the US military executed 102 GIs, mostly for the rape and murder of civilians. Only one American GI was executed for desertion, and that was army private Eddie Slovik, the subject of the media short produced by Kevin Farkas of The Social Voice Project. [click image to read more]

That’s Offensive

“We have recently become aware that several songs performed by Kate Smith contain offensive lyrics that do not reflect our values as an organization,” read an official statement from the Philadelphia Flyers sports organization. “As we continue to look into this serious matter, we are removing Kate Smith’s recording of ‘God Bless America’ from our library and covering up the statue that stands outside of our arena.” And just like that it seems, after decades of respected and celebrated status, the legendary singer and icon of American patriotism (recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom) and daughter of the South (born in Jim Crow era Virginia), is banished. Determined offensive. [click image to read more]

Those Who Shape History

As Ansel Adams said of photography, the hand of the creator is always present somewhere in the image. To fully understand a photograph, we have to discern and detect the photographer. And so it is with history, framed and brought into focus by the hand of public historians. [click image to read more]

Oh Look! Another Rust Monument

Preservationist Craig Potts says, “Historic preservation clearly does much more than preserve bricks and mortar. It recognizes that our built history connects us in tangible ways with our past and provides context for the places we occupy and the world we live in.” We agree, but we have to challenge ourselves to think beyond abstractions, and to think through the ways in which these sites can function at tangible, concrete influences in our lives. We can’t rationalize these preservation projects with feel-good nostalgia or the axiom: If it’s old, therefore it is historic. Don’t touch, stand behind the line, read about it in this brochure. Some old stuff from our industrial past is junk and certainly needs to be scuttled, clearing space to make way for new locations, new uses, new history. We desperately need room for more historically connected common spaces that openly welcome civic engagement, activity, and occupation–for the public good. [click image to read more]

Miners Memorials and Remembering

Memorials encourage us to quietly honor lost souls and to respectfully commemorate solemn occasions. Designed to evoke calming reverence, tranquility, and decorum, memorials insist on a certain code of behavior: quite please, respect the dead, proper attire requested at this sacred site. But memorials also pacify us, reminding us to hold our tongues. Shhh, this is not the place to bring “that” up. It’s too soon. Don’t be inappropriate. Respect the dead. Quiet please. But what is “that” which we are not to talk about at memorials? It is, of course, their raison d’être, the real reason we gather at memorials to honor the dead. Here lies John Smith (killed by a drunk driver, but don’t mention that here and now). [click image to read more]

Hiding History: Are You Doing Your Part?

it is possible to have very different accounts of the same historic event, for example. To a northern historian it was the war to preserve the union, but to a southern historian it might be the war against northern aggression. Of course, neither interpretation is completely accurate, but the point is that even historians edit their work according to inherent social, political, and economic values and biases–whether explicitly or unconsciously. Discerning the omission or falsification of known historic facts is relatively easy. What the public might find harder to detect is the way in which history gets subtly shaded or distorted. [click image to read more]

Museum Crimes & Misdemeanors

some local museums willingly peddle in fake history and artifacts, turning their exhibits and programs into carnival-esque road-side attractions instead of authentic history experiences: Come see our real Indian bones, look at our stolen antiquities, objectify cultures and races, and oversimplify history with a few relics (from where they came we have no idea). We think public historians–and the visiting public–should take note of this issue. We wonder, what about the local history museum in your town? What ethical code, policies, and procedures do their public historians follow to ensure that they do not peddle in stolen, fraudulent, copyrighted, ethically dubious, or culturally inappropriate artifacts? [click image to read more]

And Then There Were None

To keep the lights on, many organizations first cut back on educational programs and essential curation services such as proper preservation techniques. Then staffing gets scaled back. Volunteers are given little training or guidance. Operating hours are curtailed. Days open slim down to three, two, then one day a week, maybe one weekend a month. Budgets for utilities and groundskeeping are downsized. A leaking roof goes unattended. A broken window pane is left unanswered. Maybe, just maybe, the protective property insurance bill goes unpaid for a month or two. And finally, a responsible board of directors decides to shutter operations altogether. [click image to read more]

Traveling Through Public History

For whatever travelogues are, they do take us to places we might not have known about otherwise. A good example is a recent online article, “Travelling the Crooked Road,” by travel writer Joe Rogers. In this brief and wonderfully delightful journey, Rogers’ story (aka, road trip) “takes you on a musical journey through southwest Virginia” to give us a sense and sampling of something called Virginia’s Heritage Music Trail. As public historians, what gets our attention is the use of digital media to tell capture and preserve this slice of what we call contemporary living history. Photographs, text, and hyperlinks to supplemental information combine to give the reader a rich experience. And publishing this story to the internet gives it immediate world-wide reach, something public historians could only have dreamed of before the internet. [click image to read more]

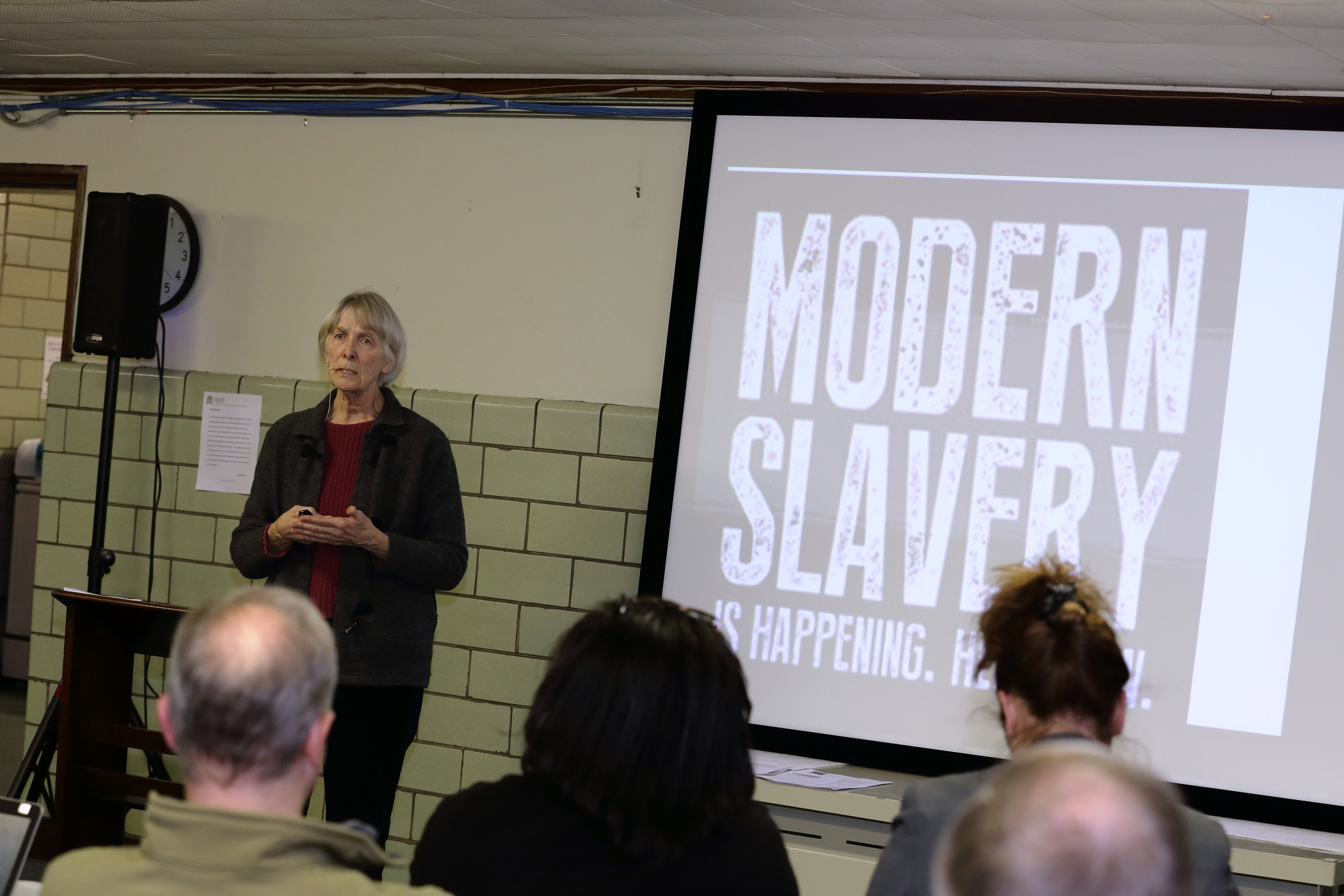

Dark History

One of the goals of recording the public event for the podcast was to create a historical record of the moment—a sociological sampling in time of community voices. It’s the kind of rich, first-hand, primary source material that historians seek and highly value. Historians may delight, but not everyone appreciated the effort. “This paints our city [of Beaver Falls] in a bad light,” complained one observer. Another said, “We’re trying hard to clean up our towns, and all this talk about crime only makes us look bad.” Someone else appreciated the public forum and informative presentations, but dismissed the idea of recording the discussion and posting it to the internet. “Sure, human trafficking and these sex crimes are a problem in the county, but people will get the wrong impression about our communities. People are safe here.” But the Beaver County Anti Trafficking Coalition would disagree: no one is safe where human trafficking and forced sex slavery exists. To pretend otherwise is foolish. To silent the voices and stories that bear witness to this horrific phenomenon is, in our view, unconscionable. As public historians, to silence the historical record on this matter is unethical and a disservice to history. Our mission is to document, preserve, and share history—including the uncomfortable issues, voices, and stories of our time. Future generations will condemn us for our silence. [click image to read more]

History(ing): A Library Does Public History

But there is another goal of the program that catches our attention, and we find it to be most interesting for public history. Toby Greenwalt, the library’s Director of Digital Strategy and Technology Integration, recently said that the music streaming service will also preserve Pittsburgh music history. “We were thinking of it as a community entity,” Mr. Greewalt said. “We have an opportunity to help document some of the work that’s being created and hopefully bridge some of the gaps and show how many styles and creators are being represented here in the city.” In this regard, the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh will be doing music history today, for tomorrow. They will be laying down the tracks—literally—for the city’s historical record. Years from now, as future generations seek to understand their music heritage, they will be able to thank the librarians who also served as public historians. [click image to read more]

Turning the Personal Into Public History

Truly, this video is of its time, not only in terms of meaning and message, but also form and function. Inasmuch as it is a powerful personal narrative (giving voice to Laura’s ethnic heritage and history), it is a tech-savvy, social media oriented production aimed at particularly contemporary (read: younger) audiences. Laura’s handheld selfie-styled camera angle is casual, informal, and as personal as your last FaceTime conversation with a friend. But keep this in mind, Laura’s just not talking to you, she’s speaking to the world. And that’s the power of digital media. Now that the BBC has gotten your attention, “Glasgow’s Slave Streets” intends to question traditional expressions of public history (i.e., street signage) that have by and large remained unquestioned. The critical issues raised here around representations, reverence, and respect for Scotland’s slave-owners is akin to how we in America are questioning representations, reverence, and respect for our own slave-owning history. The video reveals that Scotland and America share this painful, inhumane history, but we also share a contemporary effort to understand, contextualize, and question this history through a modern lens. [click image to read more]

History Reaching You

Public historians should take note of the unsubtle, direct, and honest advice Mr. Hart offers his young readers. It’s the kind of guidance rarely found in travel brochures or museum guides. It’s also what teens will be thinking about as they visit historical sites in the future–so be prepared. Younger generations are developing a keen critical awareness of history, and as this article in Teen Vogue suggests, they are discovering ways to challenge history–personally, socially, and politically. [click image to read more]

Media Makers as Public Historians

The only history that matters is the history we know. Free and open access to historical records, artifacts, and information–regardless of medium–is essential to society and democracy. In fact, our nation’s great public systems of education, history archives, and libraries are founded upon the ideal of free and open access to the public. However, we increasingly face new barriers to accessing historical information, most notably by for-profit organizations that erect pay-walls between historical information and the public. In the case of media that has historical value (as defined above), such information is increasingly restricted by their content creators. The matter is complicated of course; media creation always involves issues of intellectual property and economic value. How we negotiate these interests in the public’s interest is going to determine who controls and maintains vast segments of our historical record. [click image to read more]

Educate, Entertain, Inspire

There was in our region, history tells us, commonplace indifference toward ending slavery. It’s “just a southern thing,” was a typical sentiment, a “southern fault.” But history also reminds us that many Western Pennsylvanians were fiercely abolitionist. They viewed slavery as our “greatest national sin” that must be stopped by any means necessary–even if by war among the states. Today, as the video reveals, Americans still hold differing opinions as to the role of slavery in sparking the Civil War. These differing understandings of slavery continue to shape our political, social, and economic landscapes and influence our attitudes about race–all of which still impact and affect African Americans most deeply. Public historians, such as the media producers at Huffington Post, help us sort through these historical issues. Some public historians will, unapologetically, take sides on certain historical questions. What we the public conclude, of course, is up to us. [click image to read more]

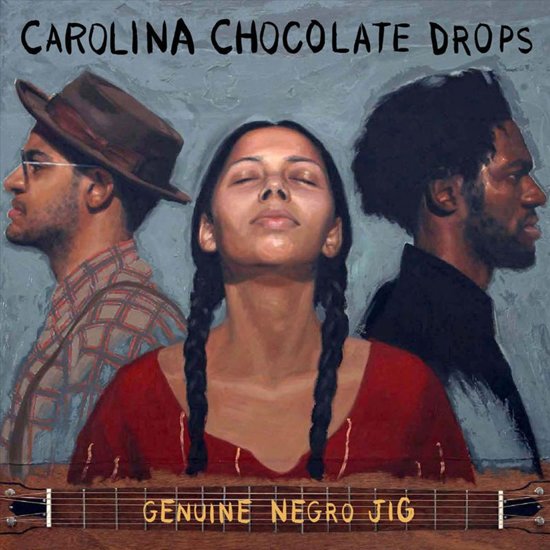

History Influencers

“Are we reenactors or are we interpreters?” asks band member Rhiannon Giddens in response to those who might think the band’s goal is to reproduce and replay music of the past. “I think we are interpreters,” Giddens asserts. “We’re living human beings. We’ve all listened to different music. We’ve grown up in this world. We can only bring what we have to the songs.” [click image to read more]

Doing Anthropology with Oral History

Anthropology demands the open-mindedness,” said social scientist Margaret Mead,” with which one must look and listen, record in astonishment and wonder . . . ” Understanding and appreciating our amazing social traditions–from how we bury our dead to how we prepare holiday meals together–is “doing anthropology.” [click image to read more]

In Your Own Words

the story Mr. Myers’ told that day was just as we expected—violent, painful, sad, and bitter. It was an honest and authentic account–in his own words–of his experience fighting (he repeated often) “those damn Japs” during the war. I like to think the way we approach our veterans oral history work (i.e., encouraging veterans to tell their stories in their own words, where ever that leads them) is important and meaningful not only for us (the public), but more importantly, for the veterans themselves who are, in many cases, still struggling for the right words, time, and place to tell their stories. [click image to read more]

Because They Speak, We Shall Listen

Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel wrote, “For the survivor who chooses to testify, it is clear: his duty is to bear witness for the dead and for the living. He has no right to deprive future generations of a past that belongs to our collective memory.” We contend that media producers also have a duty to use their specialized skills and means to bear witness to history, as did WOR Radio in the 1940s and the 2002 Peabody award winning Yiddish Radio Project produced by NPR, Dave Isay, and Henry Sapoznik. Without their foresight to reach into the past and bring these historic voices into the present, we would be a little less humane. And so we choose to listen to those who speak. Oral history matters. [click image to read more]

Thought-Provoking Oral Histories

We often think of oral history projects as stodgy and boring, mere catalogs of dates, names, places, and self-important stories with little relevance to anyone else but the interviewee. To some extent, we can’t argue with this assessment. Too many oral histories are, in fact, unappealing, especially long-form interviews. In our experience, the net effect is that these interviews are seldom heard or watched by anyone beyond the participants’ family, close friends, or interested academics or researchers. But oral histories do no have to be uninteresting. Here are a few creative and thought-provoking oral history projects that might surprise you. [click image to read more]

History Is Upon Us

I contend that we oral historians must assume more active roles and responsibilities as public historians. We must use oral history to engage and interact with the public through community-based history activities and events, speaking engagements, teaching, the writing of articles, creating videos, producing history podcasts—whatever it takes to tell these stories using the actual words and voices of our time. Again, a story not told is a story not heard. As such, let’s not be indifferent or careless about the power in our hands to shape and give life to these stories though our articles, books, museum exhibits, public forums, camera lenses, audio recordings, and video screens. Let’s not forget that what we capture, preserve, and share with the public today will certainly be what future generations know, understand, and care about history. [click image to read more]

Oral History for the Twenty-First Century

The Social Voice Project is mentioned in the chapter, “Oral History for the Twenty-First Century,” alongside StoryCorps (Library of Congress, National Public Radio) and the internationally acclaimed Memoro Project as a significant public history program that captures, preserves, and shares the voices and stories of our local communities. In reaction, we respond: “TSVP began as a forward thinking, grass-roots oral history project,” says executive producer Kevin Farkas, “and over the years we’ve been able to capture, preserve, and share hundreds of voices and stories from communities throughout Western Pennsylvania. “Unfortunately, time is never on our side,” explains Mr. Farkas. “Too many of our elders pass away before we can preserve their stories for our families, communities, and future generations. “That’s why we encourage every local historical society and museum to have some kind of active oral history program. [click image to read more]

Engage History In Real Time

In our opinion, too many local history organizations are rear facing and fixated on a static past. We think these organizations can and should actively engage the present because come tomorrow, sure enough, today will be the past. Then what? What can we do today? We think every local history organization should have some form of active community-based oral history program to celebrate, honor, and learn from the amazing lived experiences of our citizens–before this history is lost. Obituaries are not a meaningful way to learn about local history. [click image to read more]

Media Historians

History often takes for granted the photographers, videographers, and audiographers who capture, preserve, and share history as it happens. Oftentimes, none of what we record is pretty or neatly conceived. But it is the job of the media historian to get the shot or sound clip. It’s then up to the rest of us to make sense of it. [click image to read more]

Historians Want to Know: Who’s the Real You?

In the age of cellphones, social media, and digital photography, it’s estimated that people are taking 14 trillion photo images each year–many of these photos will be self-imaged, or “selfies.” So years from now, as public historians sift and sort through our collective photo-history, they will have the daunting task of determining what images are real and genuine vs staged and pretend. Years from now, as we go about putting together our family histories and look for images of great grandma on Instagram, who are we going to find? [click image to read more]

You must be logged in to post a comment.