Who's Photographing Beaver County History . . . Today?

Historical Photographs Are Important Artifacts

We often say that local historical societies and small town museums are the best kept secrets in their communities—always present, yet hidden in plain sight. “Oh that place? I visited there a long time ago when I was a kid,” people frequently say. “It’s pretty neat. They have a lot of old stuff there.”

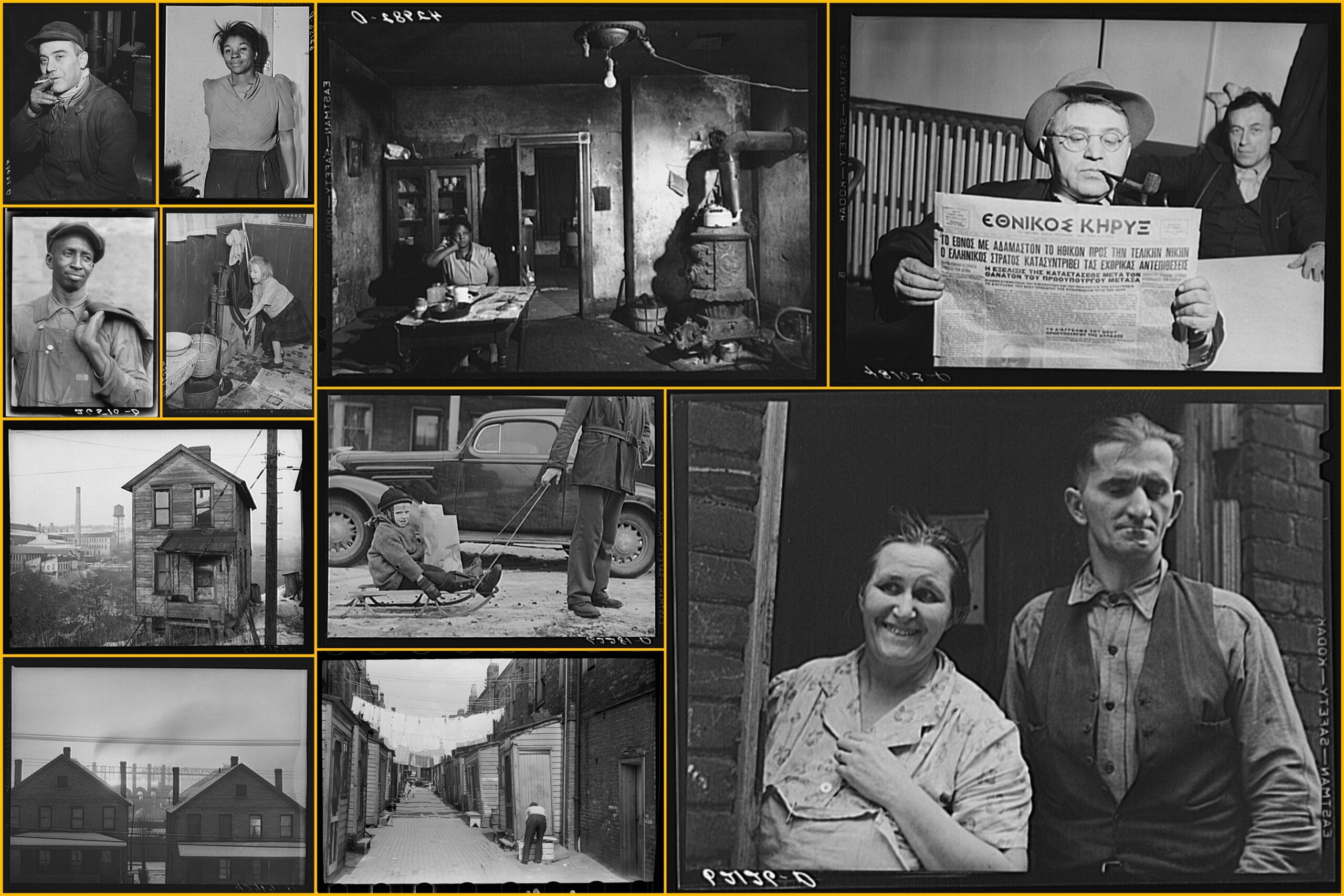

Nearly 500 Depression-era photographs taken in Beaver County, Pa between 1938 - 1941

Indeed, historical photographs are perhaps museums’ most abundant artifact. And there’s a reason. Since the 19th century, photographers—even in the smallest of towns—have been actively capturing, preserving, and sharing images of daily life, social activities, and news events. Starting in earnest during the early years of the 20th century, photography became ubiquitous, despite the relatively rare, expensive technology and skills necessary to be a photographer.

Photography would not become fully democratized until Kodak and Eastman invented photo film and handheld, snapshot-ready, easily operated cameras, such as the Brownie, so portable and convenient to use they were marketed to children and soldiers during the war years. But it was Leica’s 35mm camera invented in the 1920s (along with the flashbulb) that ushered in the concept and practice of photojournalism—the explicit and formalistic use of photography as a documentary tool.

For showing us the way to do history through photography, we owe a great debt of gratitude to the early photo-documentarians and projects adding to the historical record. A good example would be the government-sponsored project begun during the Franklin Roosevelt presidency to document aspects of the American experience between 1935 and 1946. Yale University’s Photogrammar project describes this work: “The Farm Security Administration—Office of War Information (FSA-OWI) produced some of the most iconic images of the Great Depression and World War II and included photographers such as Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Arthur Rothstein who shaped the visual culture of the era both in its moment and in American memory.”

Setting aside the political motivations underpinning this project, FSA-OWI is considered to be the largest photo document project ever created by the federal government. It leaves us with more than 170,000 historical photographs taken in cities and small towns across America. Nearly all photos are now considered in the public domain and available for historical research and display in museums. In fact, many local historical societies include FSA-OWI photographs as part of their own collections.

Today with digital photography, image making and photo-documentation is in the hands of nearly everyone on the planet, placing more than a trillion photographs onto the internet and into news papers, magazines, family albums, research archives, and photo collections of local historical societies and museums. Moreover, technology allows for old paper photographs, plates, or film negatives to be digitized added to public-facing collections for viewing.

Sizable photo collections are not a new thing, even at the local level. In Pittsburgh, near us, the University of Pittsburgh Historic Photograph collection counts more than 14, 000 images, with hundreds being made available online through digitization.

The Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh and others are now displaying digitized images through a public history initiative known as Historic Pittsburgh, partnering “with more than a dozen cultural heritage institutions willing to digitize and share their collections to support personal and scholarly research.” Even the Detre Library & Archives at the Senator John Heinz History Center contains 4,500 images documenting Pittsburgh’s past, although it is uncertain how many digitized images are available through Heinz’s non-circulating archive.

It is clear that local historical museums are increasingly breaking out of the traditional non-circulating, on-site only, brick and mortar photo archive model. For example, not far from the well established photo archives found in Pittsburgh, even the smallest history museums are able to display sizable collections of historic photographs.

Quick Survey: Historical Photograph on Facebook

Little Beaver Historical Society = 2,146 images

Beaver County Historical Research and Landmarks Foundation = 1,870 images

Beaver Area Heritage Foundation – Museum – Beaver Station = 1,849 images

Air Heritage =1,847 images

Enon Valley Historical Society = 718 images

Old Economy Village = 476 images

Beaver County Genealogy and History Center = 235 images

Merrick Art Gallery = 130 images

Rochester Area Heritage Society = 128 images

South Side Historic Village Association = 80 images

New Brighton Historical Society = 63 images

Larry Bruno Foundation = 58 images

These grass-roots (and often under-resourced) museums are now publicly displaying historical photographs on their websites and social media platforms, using tools such as Facebook photo albums. At the time of this writing, a quick online review of Beaver County museums reveals thousands of historical, organizational, and community-oriented photographs now available to the public on Facebook.

Such abundance of readily accessible photographs on the internet is remarkable, and only made available through the democratization of digital media. Any history organization—of any size or budget—with online access can now present their historical photographs to the world. Moreover, these photographs can be used in exciting new ways to educate, entertain, and inspire the public to take an interest in local history.

For example, at the Little Beaver Historical Society in Darlington, Pennsylvania (population 241), curator Dave Holoweiko reports that one particular photograph has gotten more attention than any of the thousands he’s posted online. A photograph of famous Beaver County drive-in eatery, Jerry’s Curb Service, has been viewed, commented on, and shared many thousands of times, capturing perhaps the nostalgia, fond memories, and high regard people have for this local historic landmark.

At The Social Voice Project, we’ve had a similar experience with one historical digital media posting about Conway Yard located in Freedom, Pennsylvania. This media piece describing the train yard has been viewed more than 9,785 times on our Facebook page.

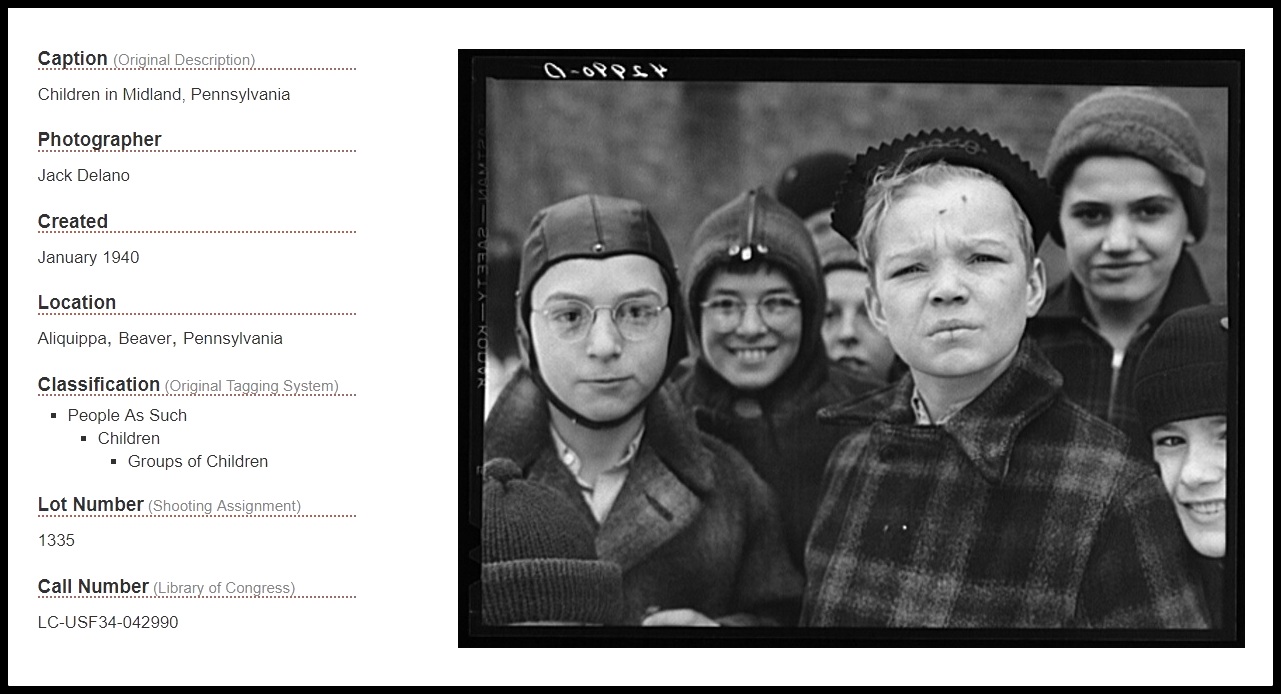

As public historians, it is our obligation to bring history forward and reveal it in meaningful ways. It is our obligation to pull it out of the non-circulating archives, take it off the shelf, dust it off, and shine a spotlight on it. It is also our job to curate and contextualize history using factual and rigorous scholarly methods and best practices. We do not serve history well by putting historical objects in a display case or posting photographs online without obligatory provenance (i.e., important information such dates, names, places, origin, etc.).

In other words, we must curate online historical photography collections as we would any other artifact collection or exhibit. To be useful, historical photography collections have to be labeled, organized, and searchable or else we might as well dump all these images into a generic shoe box and shake them up.

Metadata matters!

If local history museums don’t take the time to curate their online photographs, the best we’ll be able to say is, “Oh, there’s a lot of really neat old stuff in those pictures. What are we looking at and who are those people?”

More Essays & Critical Perspectives on Public History

Gallery with alias: PUBLIC_HISTORY_BLOG_POSTS not found

You must be logged in to post a comment.