Gallery with alias: PUBLIC_HISTORY_BLOG_POSTS not found

“NFL player Pat Tillman joined U.S. Army in 2002. He was killed in action 2004. He fought for our country/freedom.” ~President Donald Trump’s 2017 social media comment used to condemn NFL players who protest during the national anthem

“The very action of self expression and the freedom to speak from one’s heart—no matter those views—is what Pat and so many other Americans have given their lives for. Even if they don’t always agree with those views.” ~Marie Tillman, Gold Star widow, in reaction to President Trump’s evocation of her husband

In presenting social history, public historians are tasked with making sense of the stories we tell about ourselves, including our myths and legends. Perhaps the most difficult social tales to interpret and frame within history are those still in the making, such as the Legend of Pat Tillman.

Our gods do not walk among us. Instead, they live in the supernatural stories we call myths. Lesser characters of course, such as our common human heroes, are the cast of legends.

Mythological characters are often infused with mysterious religiosity and otherworldly spirituality, transcending time. But our legends tend to be more down to earth, folksy, and closer within reach. It’s the difference between Jesus and George Washington.

Unlike the gods, legendary heroes were once among the people. Usually we can place them in history (i.e., born here, died there, defeated our enemy on a certain date). Some would say that our hero legends are historicized narratives, flushing out and affirming and exalting our highest ideals and values. Heroes are extraordinary for a reason. Their stories are educative, entertaining, and inspirational. In short, our hero legends are culturally functionary. Our heroes represent and validate that which is our very best qualities.

Take for example the Legend of Pat Tillman.

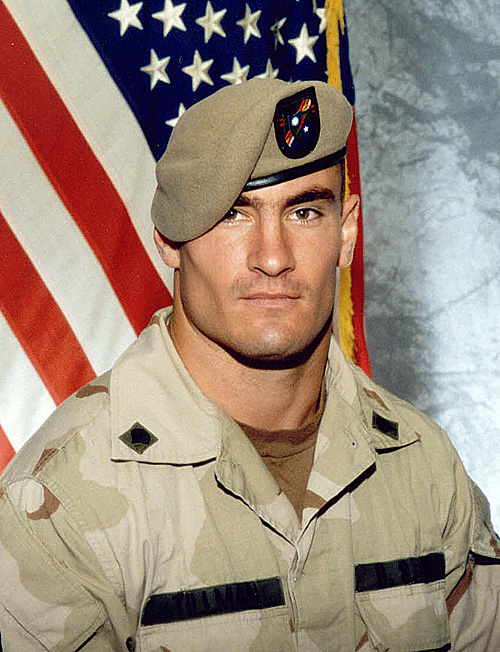

On April 22, 2004, the army soldier and former professional football star was killed in Afghanistan. Immediately, the army and government declared Tillman’s death a national tragedy; his sacrifice, they said, was valorous, deserving highest praise and recognition for heroism. Killed in battle, Tillman’s death it seemed was, no less, a selfless sacrifice upon the altar of America’s fight for freedom and justice.

For quite some time after Pat Tillman’s death, military and government officials declared him a war hero. He received the Silver Star, our nation’s 3rd highest military decoration for valor; the citation read killed “in the line of devastating enemy fire.”

Pat Tillman gave up a lucrative football career to serve his country, and he paid the ultimate sacrifice at the hands of the enemy.

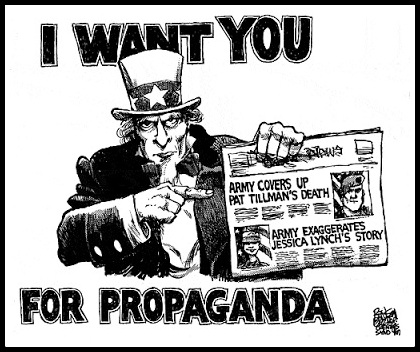

All that is true, except Pat Tillman was killed by friendly fire. Americans killed Pat Tillman. That is, of course, sometimes the tragic reality and truth of war. But that truth, military and government officials decided, was not convenient. They wanted Pat Tillman’s death to be heroic, worthy of valor, legendary.

But the story they told about Pat Tillman’s death was knowingly false and fabricated. As facts about the incident eventually emerged, the official story of Pat Tillman’s death became scandalous. Even Tillman’s own family now recognizes it as pro-war propaganda.

Six years after Pat’s death, the Gold Star Tillman family spoke out against the war and the government’s cover-up in the documentary film, The Tillman Story.

Pat Tillman never thought of himself as a hero. His choice to leave a multimillion-dollar football contract and join the military wasn’t done for any reason other than he felt it was the right thing to do. The fact that the military manipulated his tragic death in the line of duty into a propaganda tool is unfathomable and thoroughly explored in Amir Bar-Lev’s riveting and enraging documentary.

Clearly, Pat Tillman reminds us that the intersection of myth, history, and legend is a complicated and confounding space where facts and fiction sometimes coexist, each bleeding through at various times revealing something different.

The Pat Tillman story continues to evolve with each new telling. As time goes on, which Pat Tillman story will endure? And which story will public historians favor?

This post is inspired by the online post from the Zinn Education Project: “April 22, 2004: Football Star Pat Tillman Killed in Afghanistan.”

PUBLIC HISTORY MATTERS

At The Social Voice Project, we celebrate history and people through our community oral history projects that give us a chance to look, listen, and record the voices and stories of our time. We encourage all local historical societies and museums to capture, preserve, and share their communities’ lived experiences, memories, customs, and values. Future generations are depending on it.

Contact TSVP to learn more about our commitment to public history and community oral history projects.

You must be logged in to post a comment.