CRITICAL ESSAYS

& THOUGHTS ON LOCAL HISTORY

Put Your Foot In It

Black Local History in Beaver County, Pa

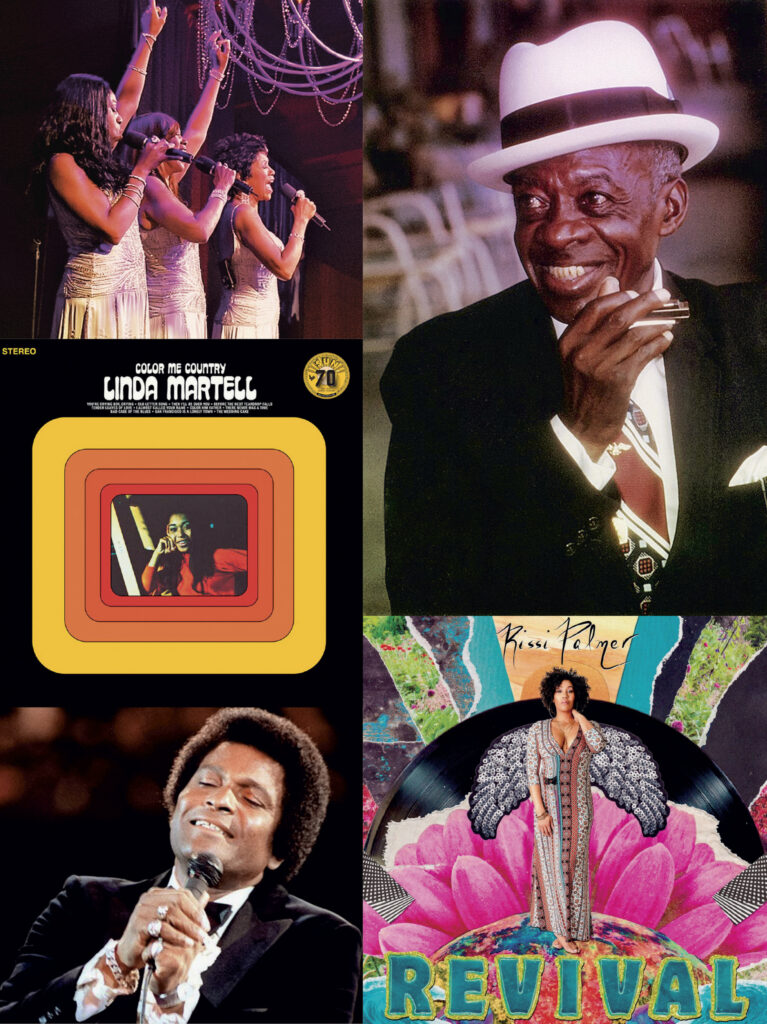

“I now know that the Black influence on country music,” writes the author, “starts at its roots with the instruments that are at the core of the “country sound”: the banjo and the fiddle. I also know about Lesley Riddle who picked and taught the Carter Family many of the songs they turned into country music canon and influenced Maybelle Carter’s “bottleneck style” of guitar picking. I know about Rufus “Tee Tot” Payne, mentor to Hank Williams and Gus Cannon, and who taught a young Johnny Cash and Arnold Shultz. These [Black] artists have yet to become the household names they deserve to be.”

The Sound of Silence

Never heard these names before? You can read about them on the “African Americans” history-on-a-stick marker on the grounds of the Beaver Train Station. There's also a fascinating mention of the St. John African Methodist Episcopal Church in Bridgewater (est. 1830) as being “the oldest African American church in the county.” Another source cites it more broadly as “the first Negro organization in Beaver County.”

Local Black Activism

We know very little about the social, economic, and political dimensions of Black abolitionist activism in Beaver County, at least in comparison to the white activist history we share and rightfully celebrate. Again, sidebar. But it need not be this way.

Local Black History

The inspiration for this essay

Black at the Roots: A lesson on country music’s lineage, By Rissi Palmer

PUBLIC HISTORY MATTERS

At The Social Voice Project, we celebrate history and people through our community oral history projects that give us a chance to look, listen, and record the voices and stories of our time. We encourage all local historical societies and museums to capture, preserve, and share their communities’ lived experiences, memories, customs, and values. Future generations are depending on it.

Contact TSVP to learn more about our commitment to public history and technical assistance in creating community oral history projects.

You must be logged in to post a comment.