Gallery with alias: PUBLIC_HISTORY_BLOG_POSTS not found

Hopped Up History

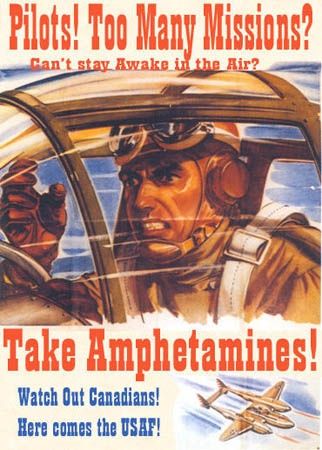

The Use of Amphetamines During WWII

History comes at us from unusual places. Take for example this online history feature by The Fix, a website about addiction and recovery that explores these issues from a wide range of perspectives, including the history of drug use. If we believe the connection between drug use and war is a modern phenomenon (think of the strung out soldiers portrayed in the 1970s movie, The Deer Hunter), this gives us something to think about.

“From booze to speed to heroin, drugs have been as big a part of military conflict as bullets,” says The Fix in “10 Wars and the Drugs That Defined Them,” a multimedia walk-through a lesser known dimension of military history. The Fix’s feature is a short but provocative take on history’s “druggiest wars.” For a more thorough treatment of the subject, check out “Combat High – How Armies Throughout History Used Drugs to Make Soldiers Fight,” at Military History Now.

As public historians, we not only present history to the public, but we also have a significant role in the interpretation of history. As educators, we always try to align our historical narratives so they are appropriate for the audiences who walk through our museums and exhibits. We use discretion. We edit. We make customizing choices about facts and stories–what to leave in or take out, underscore or underplay.

In short, public historians from the Smithsonian to local history centers control how history is presented and received based on a wide range of influencing factors, including social, economic, and political norms and values expected by our communities, museum membership, and financial supporters.

As we’ve written previously in the blogpost, Historical Hero Worship, the history of WWII often presents a particular challenge to public historians who try to present a balance between the harsh realities of war and an expectation that any history of “The Greatest Generation” serves to fulfill an idealized, if not Romantic, narrative of righteous sacrifice, deserving triumph, moral victory, and unquestionable heroism.

The truth about WWII, as will all wars, is all over the place. And it is not always pretty, safe, neat, or innocent. And neither is the mythos of heroism about WWII we allow ourselves. Observe society and notice how we tend to give WWII veterans (living or dead) carte blanche honor, despite the fact that during WWII, one third of all criminal court cases in the entire US were military courts-martial. That’s 1.7 million cases trying WWII GIs for criminal conduct. In fact, the US military executed 102 GIs, mostly for the rape and murder of civilians. That old man wearing a WWII ball cap could have spent the war years in the stockade, could have committed war crimes, could have tried everything possible to avoid the draft, could have been no hero during the war. None of these possibilities get in the way of our automatically thanking and praising him for his service.

When we use sweeping, overly generalized honorific labels such as “the greatest generation” to describe those who endured WWII, we leave little room for these darker, off key, and inconvenient truths about war that don’t serve the historical narratives oftentimes expected from our social, economic, and political norms and values. If the 102 GIs executed by the US government for heinous crimes are members of the greatest generation, where do they fit into our WWII exhibits, history school books, community memorials and monuments, Hollywood movies, and the family stories we share around the kitchen table?

We don’t expect or anticipate the possibility that Grandpa’s exploits during the war were heavily drug-fueled.

As The Fix teaches us, drug use by troops in warfare actually happened (is happening); the phenomenon is real, factual, and historically significant. Yet, this history is mostly unknown. Why is this history squelched from most WWII museums, exhibits, and historical programs? We should ask public historians about this; it might open up an important dialogue about the why and how certain histories are privileged over others, and what are the consequences for all of us.

Here’s an example of public history that opens up the topic of drug use during WWII. In “Speed: World War II (1941-1945),” historian James Holland explores how the use of amphetamines affected the course of World War II and unleashed a pharmacological arms race:

Here’s an example of public history that opens up the topic of drug use during WWII. In “Speed: World War II (1941-1945),” historian James Holland explores how the use of amphetamines affected the course of World War II and unleashed a pharmacological arms race:

By 1942 the militaries of the world had come up with plenty of reasons to take drugs: relieving boredom, treating pain, managing nerves. World War II introduced a new one—staying awake. To achieve that goal, soldiers were fed amphetamines. The Americans, British, Germans and Japanese all used speed to keep troops alert. Japanese kamikaze pilots and German Panzer were stuffed full of amphetamines to “motivate their fighting spirit.” The American military alone distributed around 200 million tablets of the drug. The popularity of amphetamines carried into peacetime, when doctors were prescribing pills for everything from depression to obesity.

This post is inspired by the episode, “World War Speed” of the PBS history series, Secrets of the Dead “explores some of the most iconic moments in history to debunk myths and shed new light on past events. Using the latest investigative techniques, forensic science and historical examination to unearth new evidence, the series shatters accepted wisdom, challenges prevailing ideas, overturns existing hypotheses, spotlights forgotten mysteries, and ultimately rewrites history.”

PUBLIC HISTORY MATTERS

At The Social Voice Project, we celebrate history and people through our community oral history projects that give us a chance to look, listen, and record the voices and stories of our time. We encourage all local historical societies and museums to capture, preserve, and share their communities’ lived experiences, memories, customs, and values. Future generations are depending on it.

Contact TSVP to learn more about our commitment to public history and community oral history projects.

You must be logged in to post a comment.