Deconstructing Local History

The Curious Case of the Wives’ Club

The Artifact

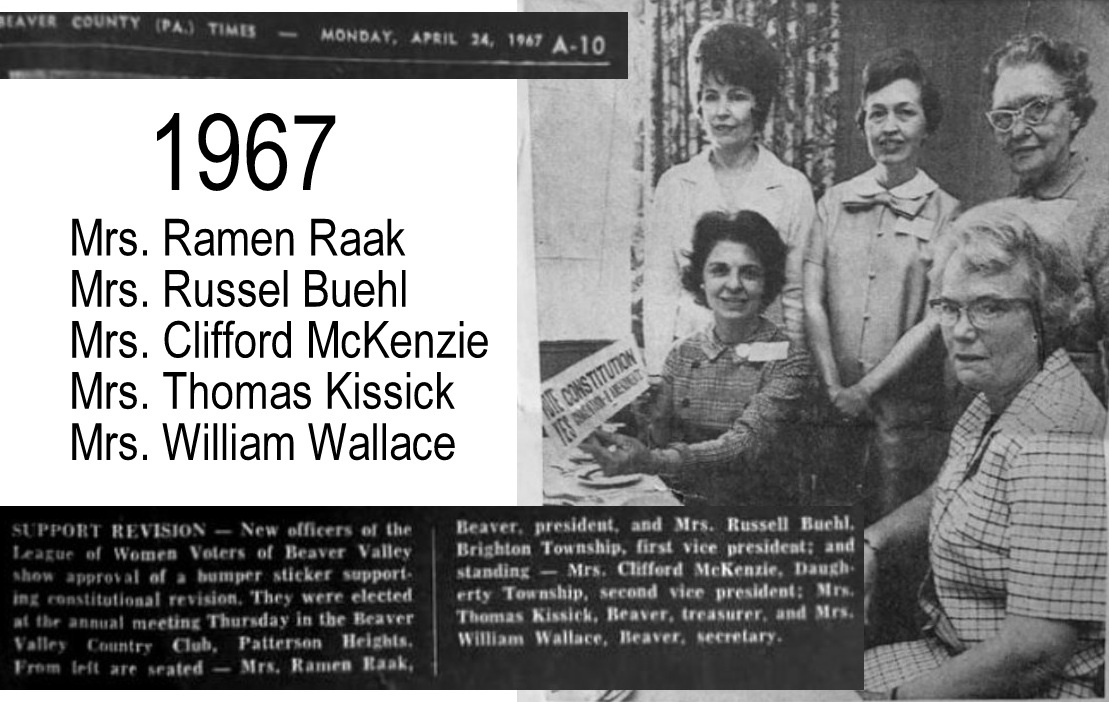

This photo is a clipping from the Beaver County Times, a local newspaper published near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The date is April 24,1967. The caption references activity of the “League of Women Voters of Beaver Valley,” a local chapter of the national organization. The women in the photo are all officers of the local chapter, that is supporting some sort of “constitutional revision.”

While the artifact itself doesn’t give us more information, there are probably enough “clues” for historians to research the subject adequately: a date, names, mention of the activity, and title of the publication are all given.

But examine this artifact more carefully and we see something else that should be of interest to historians—something that reveals social and cultural context. There is something historically significant here; it is indirect, yet obvious when we see it. Read the names of the women. Do you notice something peculiar in the way they are identified?

Not only is each and every woman referred to by her honorific married title (“Mrs.”), the reference adheres to the longstanding convention of using the husband’s first and last name, as in, Mrs. Clifford McKenzie.

This social convention has waned drastically since the 1960s, but it is still in use with some of our older generations. And for others used to seeing the convention, it goes without much critique. For those who do take notice, their reaction signifies a clear shift in social practices and cultural norms. Some might argue that this is a matter of shifting cultural mores—what is morally and ethically acceptable.

We wouldn’t know it from our historical artifact, but Mrs. Clifford McKenzie’s other name was Margaret Krupa. Her friends and family called her Marge. She lived a long and remarkably active life in Beaver County:

She was the former owner of the former McKenzie’s Lounge, Big Beaver and McKenzie’s Flower Shop, both of Beaver Falls. Marge was a member of the Holy Family Catholic Church in New Brighton. She was also a dedicated volunteer, having served as the Second Vice President then chairman of Human Resources committee and the public relations chairman for the League of Women Voters of Beaver Valley, the McGuire Guild for the McGuire Home for Exceptional Children, a United Fund volunteer for the disabled of Upper Beaver Valley, the New Brighton Public Library, the Merrick Art Gallery Association, the Holy Family Eucharistic Minister, Christian Mothers, C. D. of A., Bingo Kitchen worker and was the head decorator for all holidays at Holy Family. [Obituary of Margaret K. “Marge” (Krupa) McKenzie].

Yes, Margaret was married to Clifford McKenzie (at least by 1967), but she was also married to John Mitchell, who in 1945 was killed in action during WWII. Clifford died in 1991 leaving Margaret widowed for the remaining twenty years of her life. We wonder if in these years Margaret referred to herself as Mrs. Clifford McKenzie, as was the traditional custom for widowed women of her era. By the time she died in 2015, that custom was surely a social anachronism.

But why does any of this matter? We have to remember that historical artifacts are always contextual—created in situational social, cultural, political, and economic frames of reference. And they are received in situational frames of reference that help us interpret their meaning. The primary context refers to when the artifact was created, but just as important to understand are contexts in which they are received or “read” by historians and the public.

To fully and meaningfully understand an artifact, we have to be aware of these multiple contexts. This is a matter of critical and historical literacy. We read and write history in the same way we do other texts, using a wide range of knowledges (e.g., historical events, socio-cultural practices) and competencies (e.g., linguistic, research, logic) to help us effectively and more fully understand, interpret, and evaluate historical things.

Through the heuristic technique of textual deconstruction (see sidebar), we open up this historical artifact to more questions, such as who labeled the women by their married titles—the reporter, a photo editor, or did the ladies identify themselves this way. The practice would have fit the times, of course, but these women were activists and leaders in one of the nation’s leading women’s rights organization, champions of the Equal Rights Amendment and key player in the feminist movement of the day. Part of this movement focused on up-ending traditional social formations of women’s identity in the workplace and at home. This effort encouraged women to be more independent and self-identifying–to come out of the subordinating shadows cast by their husbands’ names. The Mrs. Clifford McKenzies of the world were becoming Mrs. Margaret McKenzie or Mrs. Margaret Krupa-McKenzie. Already in motion were shifts in sensibilities, especially in business and journalism, whereby it became proper and best practice to give women the title of “Ms.” rather than “Mrs.” or “Miss.”

Given this historical context of the late 1960s, again let’s go back to our newspaper clipping. Why in 1967 were the socially and gender conscious activist officers of the League of Women Voters of Beaver Valley identified simply as wives of their husbands?

The original intent of the newspaper story and our photo was most certainly not an expose on gender identification. It was simply local news reporting about a civic organization. But though deconstructing the artifact as we find it, we can formulate a more interesting historical research question, one that we may never have thought of without some effort to critically “read” this artifact and apply a textual analysis–revealing not one single meaning, but rather many often conflicting meanings.

Deconstructing History

Historical objects can be read like texts, where meaning is encoded and decoded according to social, cultural, political, and economic frames of reference.

A deconstructive approach to history involves revealing and understanding obvious as well as underlying, tacit, and implicit assumptions evident in artifacts and other elements of the historical record.

Deconstruction seeks to understand not only the meaning(s) of historical objects, but the relationship between meaning and object.

How and why is meaning created and for what ends or purposes?

What discernable subtexts are there?

What are the relationships between explicit/implicit or overt/covert meaning?

Gallery with alias: PUBLIC_HISTORY_BLOG_POSTS not found

PUBLIC HISTORY MATTERS

At The Social Voice Project, we celebrate history and people through our community oral history projects that give us a chance to look, listen, and record the voices and stories of our time. We encourage all local historical societies and museums to capture, preserve, and share their communities’ lived experiences, memories, customs, and values. Future generations are depending on it.

Contact TSVP to learn more about our commitment to public history and technical assistance in creating community oral history projects.

MORE ESSAYS & THOUGHTS ON PUBLIC HISTORY

You must be logged in to post a comment.