Gallery with alias: PUBLIC_HISTORY_BLOG_POSTS not found

Watermarking History

(Laying Claim to the Public Domain)

Some of the work public historians do is create interpretive displays around significant dates, events, or other historical subject matter. Take for example a local history museum’s commemoration of WWII, featuring hometown memorabilia, artifacts, newspaper clippings, and oral history interviews with veterans.

To give the public visual context of the era, the curator decides to include a variety of local, national, and international images. Small but significant, the museum’s own historical photo collection provides a local perspective. For other images—especially some of the most iconic photographs of the war era—the curator searches the internet to tap into a vast wealth of WWII images in the public domain—free to use and display by anyone.

Google “WWII photographs” and we have instant access to thousands of amazing images. The abundance is overwhelming. Yet it seems that the vast majority of photos that first appear in our searches are watermarked by companies such as Pathe, Getty, Corbis, and Alamy.

Watermarking is common in photography. It is an overlay of some symbol, pattern, or name to identify ownership or copyright control over an image. In the example below, Alamy has watermarked the famous WWII “We Can Do It!” poster made by J. Howard Miller in 1943. Produced by the Office for Emergency Management War Production Board, a government agency, the poster can be found in the National Archives.

Watermarking is common in photography. It is an overlay of some symbol, pattern, or name to identify ownership or copyright control over an image. In the example below, Alamy has watermarked the famous WWII “We Can Do It!” poster made by J. Howard Miller in 1943. Produced by the Office for Emergency Management War Production Board, a government agency, the poster can be found in the National Archives.

As a general rule in the United States, images such as this poster are considered in the public domain because it was published in the US between 1925 and 1977 without a copyright notice. Generally speaking, creative works by the United States government (e.g., Office for Emergency Management War Production Board) are excluded from copyright law and are considered to be in the public domain.

We Can Do It! is clearly in the public domain, yet Alamy’s watermarking suggests otherwise. Similarly, other commercial digital media companies such as Pathe, Getty, and Corbis also watermark historic photographs, films, and other media. For a fee, they will lift the watermark for us and give us access to something we already own.

Is this legal? Sure it is.

For public historians, the question is whether this media fee-for-access service is valuable. It can be. Dave Holoweiko is a public historian at Little Beaver Historical Society near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The museum specializes in local industrial history, such as steel making throughout the Beaver Valley–a region at the center of many organized labor struggles. On the internet Mr. Holoweiko located a very rare 1937 film depicting a violent riot of metalworkers on strike in the nearby town of Ambridge:

Iron and steel workers on strike. Sign in background reads “Steel and Metal Workers Industrial Union”. Some of the men are carrying sticks. A car pulls up and armed men get out, they talk with the strikers who shout at them to go away. More armed men (wearing arm bands) walk down the street guns held at the ready. One of the armed men takes a stick from one of the strikers and hits him with it. The strikers shout at this action. The men with arm bands start moving the strikers back and then the two sides start beating each other. The men with guns then start firing – both live rounds and tear gas. Two men inspect a dead body at the road side. More shots are fired. A man carries a wounded colleague away over his shoulder.

In this case, British Pathe (which represents the Reuters historical collection among others) claims ownership of the film, which may be considered questionable. Nonetheless, the film appears only to be available through Pathe and they do watermark the film on the internet, making it available (sans watermark) for a licensing fee.

To Mr. Holoweiko, having access to such a rare and important film for his museum’s exhibit was well worth the price.

Indeed, paying to lift the watermarks on media may be the only way historians can, in fact, bring some of their projects to the public with a degree of aesthetic quality. After all, who wants to see a collection of images plastered with distracting commercial watermarks? And distracting they are. In fact, blatant watermarking makes these images nearly unusable to public historians. However, it might take some searching beyond what Google first throws our way, but thankfully many images in the public domain can be found on the internet without watermarks.

WATERMARKING LOCAL HISTORY

We might not like the practice of watermarking public domain images by commercial ventures, but we can understand their motive: to make money. But we’ve noticed that others have gotten into the act of watermarking historical photos in the public domain–not for money–but as a way to mark origin of the images.

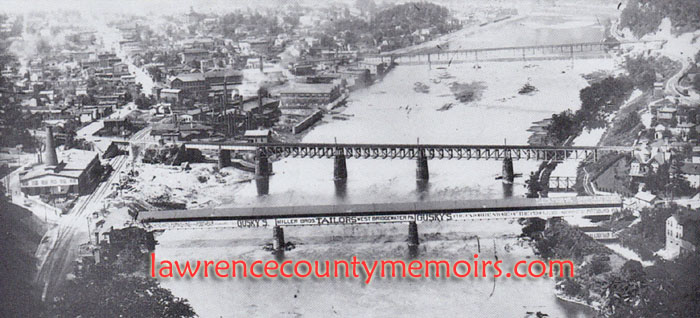

James J. Bales Jr. operates an online local history website called, Lawrence County Memoirs–a site “designed to document various aspects of the history of Lawrence County & surrounding areas in Western Pennsylvania.” By any measure, Mr. Bale’s work is a valuable and significant asset to the local history community and the public. He has taken the time to collect and document many important historical stories of the area–including an abundance of historical photographs that he obtained from the internet, or we presume by visiting the archives of various surrounding historical museums and societies and replicating them. Either way, his archive of local historical photographs is impressive, and it’s to be considered highly useful to the public–except for his peculiar and unnecessary watermarking of the images.

Nearly every historical image in his collection, many of which are to be considered in the public domain, bears the watermark “lawrencecountymemoirs.com.” The marks are bold and prominent, but they seem to serve no other purpose than to indicate they are made available by Mr. Bales on the internet at Lawrence County Memoirs. However, unlike Pathe, Getty, Corbis, or Alamy, Mr. Bales is not seeking to monetize his effort by lifting the watermarks for a fee. In fact, he clearly states on his website that his purpose is “to promote the older material in a purely educational and non-commercial manner.” Here is his full disclosure:

The written text, all recent photos, and some of the older photos published here are the property of James J. Bales Jr. The old postcards and photos published are done so in the belief that based on their age they are in the public domain. All donated materials are printed by permission of the donor and remain as their property. The copyrights to all newspaper articles displayed that were published prior to January 1, 1923, are said to have expired by law and now in the public domain. I do have some articles from 1923 and later, but I use some by permission and others by way of the Fair Use statute – and I make sure I clearly reference the material and date it was published. It is not my intention to usurp on any copyright holder’s rights but only to promote the older material in a purely educational and non-commercial manner. I do not make money, take monetary donations, or place third-party advertisements on this site. If you can legally claim a copyright over any of the photos displayed here simply contact me and the issue will be quickly resolved to your satisfaction. If you would like a particular photo posted on this site send me an email. This site is about the expansion of education and not the hoarding of information. I have a simple rule in handling requests for photos: I never, ever ask for payment or even postage, but would simply like another photo in return to further along my effort. Take care. Jeff

Copyright @ 2011. All Rights Reserved by James J. Bales Jr.

If we think of the benefits of copyrighting images beyond endowing commercial interests, then maintaining creative control, safeguarding against duplicitous and exploitative uses, and generally protecting the integrity of the photos are important rights to claim. The act of watermarking an image for these purposes is legitimate and understandable–if not lauded. Ironically, historical photographs in the public domain cannot be protected in such a way by watermarking. In fact, we would argue that the very act of watermarking such images takes away from their original value and usefulness as a public asset. Watermarking is visual alteration, and some would say that it injures the integrity of photographs much in the same way corrective restoration or colorization might affect the originality of an image.

HISTORICAL PHOTOGRAPHS ARE IMPORTANT ARTIFACTS – SHARE THEM ETHICALLY

As we’ve written before, historical photographs are perhaps museums’ most abundant artifacts, and with internet technology, even the smallest museums are now publicly displaying historical photographs on their websites and social media platforms, using tools such as Facebook photo albums.

A quick online review of Beaver County museums reveals thousands of historical, organizational, and community-oriented photographs now available to the public on Facebook:

-

-

- Little Beaver Historical Society = 2,146 images

- Beaver County Historical Research and Landmarks Foundation = 1,870 images

- Beaver Area Heritage Foundation – Museum – Beaver Station = 1,849 images

- Air Heritage =1,847 images

- Enon Valley Historical Society = 718 images

- Old Economy Village = 476 images

- Beaver County Genealogy and History Center = 235 images

- Merrick Art Gallery = 130 images

- Rochester Area Heritage Society = 128 images

- South Side Historic Village Association = 80 images

- New Brighton Historical Society = 63 images

- Larry Bruno Foundation = 58 images

-

Any history organization—of any size or budget—with online access can now present their historical photographs to the world. Such abundance of readily accessible local history photographs on the internet is remarkable, and only made available through the democratization of digital media. Moreover, these photographs can be used in exciting new ways to educate, entertain, and inspire the public to take an interest in local history.

But legally speaking, many of these local history photo archives contain images that are in the public domain, and anyone may use these images free and clear of any restrictions–including watermarking them and publishing them elsewhere on the internet. But is this ethical?

Dave Holoweiko of the Little Beaver Historical Society comments, “I don’t have a problem with photo owners marking them with a watermark. What’s upsetting is when a site or even someone who is trying to sell photos takes a photo from a public collection, watermarks them, and does not give attribution to the actual owner of the photo [i.e., the historical collection or archive]. I give source attribution to any photo in our collection and I expect attribution in return when people take from our archive. But I sure don’t watermark anything I share.”

OUR POSITION

Copyright law is complicated, especially in the digital age and where public domain media is now so widely accessible. Unfortunately, photographs and other media in the public domain are subject to exploitation by commercial interests or those who simply stake their identity to these works. Some of the legal and ethical issues include:

-

-

- Can someone alter an image in the public domain (e.g., colorize it, remove blemishes, re-crop it) and then claim that they own the rights to that image because of the alterations they made?

- How much altering is sufficient to claim ownership of an image that is in the public domain?

- Does a simple watermark rise to the level of sufficient alteration to warrant ownership of an image in the public domain?

- Can one freely re-publish a public domain image that has a watermark on it?

-

After researching these questions, here is what we conclude:

-

-

- No one can copyright an image if they do not own it.

- No one can copyright an image in the public domain.

- An image in the public domain could be copyrighted if it is altered to be significantly different from the original.

- A watermark affixed to an image in the public domain otherwise not altered or not significantly altered is not protected by copyright.

- An image in the public domain is not protected by copyright simply because it is reprinted or reproduced in a copyrighted book or on a copyrighted website.

- A collection or exhibit of images in the public domain can be claimed by copyright, but not the images themselves.

-

Like most things in life, the treatment of historical photographs in the public domain comes down to a matter of respect for their intrinsic and original value to the public (i.e., they should be considered legally and in spirit as in the public interest). For public historians, the matter is also about professional ethics. As such, here are some suggestions for public historians:

Don’t alter images

Don’t republish images without permission of the copyright owner

Attribute the source archive or collection

Don’t watermark images in the public domain

Instead of watermarking images, provide attribution or annotation as a caption or footnote

PUBLIC HISTORY MATTERS

At The Social Voice Project, we celebrate history and people through our community oral history projects that give us a chance to look, listen, and record the voices and stories of our time. We encourage all local historical societies and museums to capture, preserve, and share their communities’ lived experiences, memories, customs, and values. Future generations are depending on it.

Contact TSVP to learn more about our commitment to public history and community oral history projects.

You must be logged in to post a comment.