Black History and the Underground Railroad in Beaver County

Beaver County Black History

Excerpts: History of Beaver County, Pennsylvania, Part 1 (Bausman, 1904)

James Nicholson, a farmer in Big Beaver, owned three slaves— Pompey and Tamar Frasier and Betsy Mathews. At Mr. Nicholson's death he willed the farm to these three slaves. Soon the two Frasiers died, and Betsy then owned the farm and was married to a man named Henry Jordan in 1840. Betsy then sold the main part of the farm, and upon this the borough of New Gallilee was afterwards built.

During 802, Samuel Glasgow of Hanover Township is listed as owning one slave. (Bausman's History of Beaver County, Part 2, p. 1215)

About 1802, Samuel Johnson of the Borough of Beaver is listed as owning one slave. (Bausman's History of Beaver County, Part 2, p. 1223)

In 1772, [Levi Dungan] with his wife and two or three small children and two slaves, one named Fortune and the other Lunn removed to this section, where he located at the head of King's Creek a tract of one thousand acres — land now within the limits of Hanover township. He settled where the village of Frankfort Springs now stands . . . The two slaves of Levi Dungan, named above, remained with him until they died.

Isaac Hall, a black man, was bought at an auction in New Orleans by Captain John Ossman, in 1810, for $170, and brought to this county, where he remained a slave until his death.

Henry and Henley Webster, two slaves of John Roberta, of Hanover township, were brought with their master to this county from Virginia, and remained here until they worked out their purchase money and keeping.

Text and footnote #2, pp. 152-153.

"Gave a colored man who lives in New Castle, 50 cents to assist in relieving his son who is imprisoned in Virginia, having been sold as a slave by a drover."

~From the diary of Beaver County physician Dr. Dilworth (d. 1868), c. 1850s, as quoted in Bausman. p. 1288). Note: it is estimated that $2,200 in 1850 would equal $86,518 in 2024, and $1 would equal $39 today.

Notable People & Events

1830 – St. John African Methodist Episcopal Church in Bridgewater was established. It was the oldest African American church in the county. ["The St. John African Methodist Episcopal Church, West Bridgewater, was founded in 1830, as part of the Allegheny Mission, by a group of former slaves, five years before the incorporation of the Borough of West Bridgewater. This was the first Negro organization in Beaver County (Source: church website)]

January 28, 1836 - The Greersburg Resolution against slavery was drafted at a meeting at Greersburg Academy.

1840 – Betty Mathers, the former slave of Big Beaver farmer James Nicholson, inherited his land which she eventually sold to form the borough of New Galilee.

1847 - Arthur Bullus Bradford founded the Darlington Free Presbyterian Church over the question of slavery. Bradford was nationally recognized as an important leader of the Underground Railroad.

December 5, 1850 – A large anti-slavery convention was held in New Brighton which adopted a resolution against the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.

March 13, 1851 - Richard Woodson (aka Richard Gardiner) was seized by slave catchers and returned to slavery in Kentucky. Local citizens collected money to purchase his freedom.

1860 - William Patrick Ormes was born a slave in Maryland, escaped to Pennsylvania in 1835 and moved to Beaver County. Ormes and his sons drilled one of the first producing oil wells in the county.

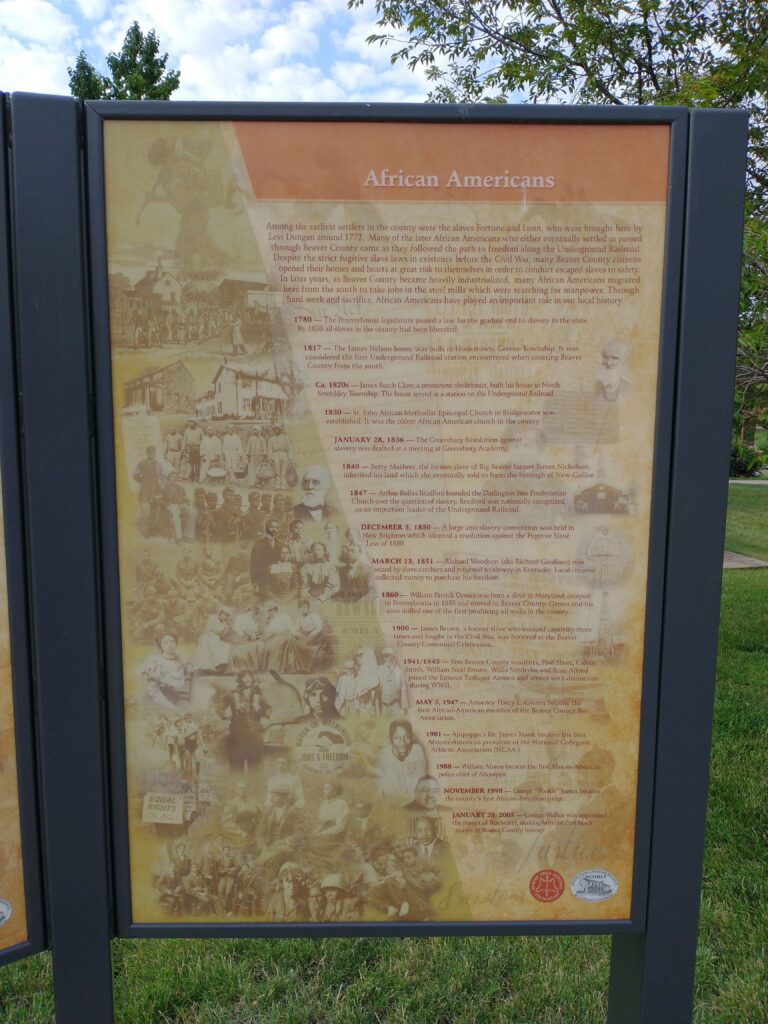

A Nod to Beaver County African Americans: Historical Marker

Inscription: Among the earliest settlers in the county were the slaves Fortune and Lunn, who were brought here by Levi Dungan around 1772. Many of the later African Americans who either eventually settled or passed through Beaver County came as they followed the path to freedom along the Underground Railroad. Despite the strict fugitive slave laws in existence before the Civil War, many Beaver County citizens opened their homes and hearts at great risk to themselves in order to conduct escaped slaves to safety. In later years, as Beaver County became heavily industrialized, many African Americans migrated here from the south to take jobs in the steel mills which were searching for manpower. Through hard work and sacrifice, African Americans have played an important role in our local history.

1780 – The Pennsylvania legislature passed a law for the gradual end to slavery in the state. By 1830 all slaves in the county had been liberated.

1817 – The James Nelson house was built in Hookstown, Greene Township. It was considered the first Underground Railroad station encountered when entering Beaver County from the south.

1830 – St. John African Methodist Episcopal Church in Bridgewater was established. It was the oldest African American church in the county.

January 28, 1836 – The Greersburg Resolution against slavery was drafted at a meeting at Greersburg Academy.

1840 – Betty Mathers, the former slave of Big Beaver farmer James Nicholson, inherited his land which she eventually sold to form the borough of New Galilee.

1847 – Arthur Bullus Bradford founded the Darlington Free Presbyterian Church over the question of slavery. Bradford was nationally recognized as an important leader of the Underground Railroad.

December 5, 1850 – A large anti-slavery convention was held in New Brighton which adopted a resolution against the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.

March 13, 1851 – Richard Woodson (aka Richard Gardiner) was seized by slave catchers and returned to slavery in Kentucky. Local citizens collected money to purchase his freedom.

1860 – William Patrick Ormes was born a slave in Maryland, escaped to Pennsylvania in 1835 and moved to Beaver County. Ormes and his sons drilled one of the first producing oil wells in the county.

1900 – James Bruien, a former slave who escaped captivity three times and fought in the Civil War, was honored at the Beaver County Centennial Celebration.

1941/1945 – Five Beaver County residents, Paul Short, Calvin Smith, William Neal Brown, Willis Sanderlin and Rosa Alford joined the famous Tuskegee Airmen and served with distinction during WWII.

May 5, 1947 – Attorney Harry L. Garrett became the first African-American member of the Beaver County Bar Association.

1981 – Aliquippa’s Dr. James Frank became the first African-American president of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA)

1988 – William Alston became the first African-American police chief of Aliquippa.

November 1998 – George “Tookie” James became the county’s first African-American judge.

January 20, 2005 – George Walker was appointed the mayor of Rochester, making him the first black mayor in Beaver County history.

Supplemental Information for this Marker

Topics and series. This historical marker is listed in these topic lists: Abolition & Underground RR • African Americans • Churches & Religion • Industry & Commerce. In addition, it is included in the African Methodist Episcopal Zion (AME Zion) Church, and the Tuskegee Airmen series lists. A significant historical date for this entry is January 28, 1836.

Location. 40° 41.879′ N, 80°

17.836′ W. Marker is in Beaver, Pennsylvania, in Beaver County. Marker is on East End Avenue just south of 3rd Street (Pennsylvania Route 68), on the right when traveling north. Touch for map. Marker is at or near this postal address: 284 East End Ave, Beaver PA 15009, United States of America. Touch for directions.

Other nearby markers. At least 8 other markers are within walking distance of this marker. Women in Beaver County (here, next to this marker); Military Service (here, next to this marker); Famous Athletes (here, next to this marker); Transportation (a few steps from this marker); Properties On The National Register of Historic Places (a few steps from this marker); Labor Movement and Wagner Act (a few steps from this marker); Immigration and Migration Patterns (a few steps from this marker); Growth And Decline 1946-1985 (a few steps from this marker). Touch for a list and map of all markers in Beaver.

PUT YOUR FOOT IN IT

The silence of Beaver County Black local history is deafening. That may be an exaggeration to some, after all, our pantheon of historical figures recognize such Black notables as James Howard Bruien, Lem Dawson, Betty Mathers, Richard Woodson, William Patrick Ormes, Paul Short, Calvin Smith, William Neal Brown, Willis Sanderlin, Rosa Alford, Harry, L. Garrett, Dr. James Frank, William Alston, George “Tookie” James, and George Walker.

Never heard these names before? You can read about them on the “African Americans” history-on-a-stick marker on the grounds of the Beaver Train Station. There’s also a fascinating mention of the St. John African Methodist Episcopal Church in Bridgewater (est. 1830) as being “the oldest African American church in the county.” Another source cites it more broadly as “the first Negro organization in Beaver County.”

Of course, Beaver County Black history wouldn’t be incomplete if it didn’t include notable white Beaver Countians such as our engineers and conductors of the Underground Railroad: James Nelson, James Beach, Arthur Bullus Bradford, the Townsend family, Dr. David Stanton, Sarah Jane Clarke Lippincott, James Edgar, Lydia Irish, and so many more heroic abolitionists. They certainly lived out the principles of their faith and risked a lot to ensure the equality of all human beings before God.

The historical record revealing Beaver County Black history is actually detailed—all things considered, as much as our local historians captured and preserved it. But let’s face it, white history has always been privileged over all others by design or accident. The Black experience—like that of so many other marginalized groups—tends to be a sidebar of history, as it is in Beaver County

Historian Henry Louis Gates points this out in his thoughtful essay, “Who Really Ran the Underground Railroad?” Addressing common myths he writes, “The Underground Railroad and the abolition movement itself were perhaps the first instances in American history of a genuinely interracial coalition, and the role of the Quakers in its success cannot be gainsaid. It was, nevertheless, predominantly run by free Northern African Americans, especially in its earliest years.”

And all “those tunnels or secret rooms in attics, garrets, cellars or basements? Not many, I’m afraid. Most fugitive slaves spirited themselves out of towns under the cover of darkness, not through tunnels, the construction of which would have been huge undertakings and quite costly. And few homes in the North had secret passageways or hidden rooms in which slaves could be concealed.”

If it’s true that the Underground Railroad was, as Gates contends, a mostly northern phenomenon and result of “white and Black activists,” then surely our Beaver County local historians would have left us with a much more accurate and balanced account of the workings of the Underground Railroad running through our county. But they did not. We know very little about the social, economic, and political dimensions of Black abolitionist activism in Beaver County, at least in comparison to the white activist history we share and rightfully celebrate. Again, sidebar.

But it need not be this way. In an edition of Milestones: The Beaver County History Journal (21:2), there is a mention of the “African American Folk History Organization” started in 1990 by Gertie Mae Young of Beaver Falls:

“Meetings were held at the Carnegie Library in Beaver Falls. The reason for this organization is that no mention of the Black Community’s accomplishments are ever made. Most of the banks and other establishments always told stories of the White Community, and we wanted people to be aware of the fact that African Americans played an important role in our community as well.

“The organization was named because of the present and past history of the Black Community. We have entrepreneurs, senior citizens that have excelled in many areas, as well as students who do exceptionally well in academics and/or sports. We wanted to bring these people and history to the forefront so that all might see the positive Blacks in Beaver County. The motto of the African American Folk History Organization is ‘History is Present!'”

Unfortunately, an attached note from the editor reads: “As of Dec. 2010 little if any progress has been made on this project. It is a worthwhile effort, and would be a valuable addition to Beaver County History.”

More recently, teacher Kenisha Page at Baden Academy started an internet project called, Beaver County Black History: “We want the students of Beaver County to discover the rich history of our community’s active fight against racial inequality, particularly our role in the Underground Railroad. Find in our web pages lessons that allow you to lead your students to discover and celebrate areas in western PA where the underground railroad served thousands of escaping slaves.”

Unfortunately, this promising effort also seems to have stalled out a few years ago. But this is not uncommon. “No one is stopping us from being involved in the Beaver County local history community,” Karen Florence lamented on an episode of the Beaver County History Podcast (Episode 12: “Beaver County Soul Food”). “We, as Black people, are just not doing it. We have to blame ourselves for not keeping this history alive.”

And this brings us back around to the silence of Beaver County Black local history. Who are our black public historians? What projects are dedicated to capturing, preserving and sharing the voices and stories of local African Americans? Are there any local history museums or heritage societies dedicated to the Black experience in Beaver County?

How long will we ponder these issues?

“Put Your Foot In It” by Kevin Farkas appears in the Public History Matters Blog, a series of critical essays about public history, local history, and historiography.

Black History Made Visible

On episode 12 of the Beaver County History Podcast, we talk with Karen Florence and Florence Cuspard Lott about the African American experience in Beaver County, and why it is important to recognize soul food as a significant part of Black history and heritage.

Episode 12 of the Beaver County History Podcast was inspired by a noticeable lack of any reference to African American foodways, food heritage, or the black immigration experience in Beaver County as part of programming for the 2019 Beaver County History Celebration Weekend. Of particular note is the absence Black foodways and culture as part of Aliquippa’s B.F. Jones Memorial Library. Historically, Aliquippa can be considered the center of Black immigration to the county, as well as the most populated Black community. In addition, it might be said that Aliquippa has been and remains central to understanding the Black experience in the county.

Therefore, it seemed egregious for African Americans not to be included among other ethnic and immigrant groups during the 2019 History Celebration Weekend. To remedy this unfortunate absence, the Beaver County History Podcast–produced independently by The Social Voice Project–reached out to Karen Florence and Florence Cuspard. They agreed to appear on the podcast to speak about the African American experience in Beaver County and why it is important to recognize soul food as a significant part of Black history and heritage.

For a wider perspective, below is the official brochure for the 2019 Beaver County History Celebration Weekend, produced by the Beaver County Historical Research and Landmarks Foundation and Beaver County’s Office of Tourism. There is no reference to African American foodways, food heritage, or the black immigration experience as part of programming offered by any participating local history organization. It is unknown if local historan Jeff Snedden’s keynote presentation, “The History of Food in Beaver County,” made any refernce to Aftican American foodways.

You must be logged in to post a comment.