Black History and the Underground Railroad in Beaver County

The Black Experience

The Underground Railroad

Early slaves in the county - The slaves who lived in Beaver County seem to have been thought of as more than servants.

Levi Dungan, a Beaver County pioneer who settled near Frankfort Springs in 1772, had two slaves, identified as Fortune and Lunn. Lunn had a favorite spot on the property where an apple tree grew. He asked that Dungan bury him under the tree when he died. Dungan fulfilled that request, and for many decades, the tree was known as “Lunn’s Tree.”

The Nicholson family were among the early settlers in Big Beaver. They brought with them three slaves: Pompey Frazer, Tamar Frazer and Betsy Mathers. All three were included in the inheritance of the Nicholson estate. Prior to her death in 1872, Mathers sold most of the land, which now makes up a large portion of New Galilee. All three former slaves are buried near the Nicholson family in Mount Pleasant Cemetery

Many amusing and pathetic incidents are related of the fugitives. One fellow reached Enon with only a blanket on and a hole in it through which his woolly head protruded. He did not know his name but thought it was "Cuffy" or "boy." He had left a boat at Rochester. A Mercer County farmer kept him and gave him the alliterative name of "Daniel Dossle."

On the other hand several slaves while escaping were pursued, and, about to be overtaken, risked a passage on the ice in the Ohio River and one of their number was drowned within the limits of Beaver County.

In the southwest corner of the home, there was a secret cellar. Although Linville recognizes the Berry family members were not documented as conductors in the 1880s and 1890s, she wrote that it "seems obvious” a secret cellar would not have been built into the home unless they intended to use it. The book even states the property owner’s son, J. Crawford, had reportedly said, “The truth was, the station had been built for a special purpose, to secret fugitive slaves hoping and trying to make the land of freedom, when pursued closely by their masters.”

Local historical accounts occasionally mention the underground railroad operations which provided a secret means of aiding escaped slaves in hiding from their masters and in transferring them northward out of reach of slavery.

Several buildings in Greene County were important stations in one of the principal underground railroads in the Civil War era.

One of the most noted lines of escape for southwestern Pennsylvania crossed the Mason and Dixon line about one-half mile south of Mt. Morris on the Morgantown-Mt. Morris Road.

At or near Mt. Morris this "Railway" was said to have branched. One branch led northeastward by way of Bob Maple's Mill, at the mouth of Dunkard Creek, Beesontown (now Uniontown), Indiana, Punxsutawney and New York State to Canada. The other was routed by way of a Mr. Leonard's farm near Leonardsville and Burnsville, in Washington County, and northward into Canada. A society of Quakers, near this line, history relates, took an extremely active part in the escape of countless numbers of negro slaves.

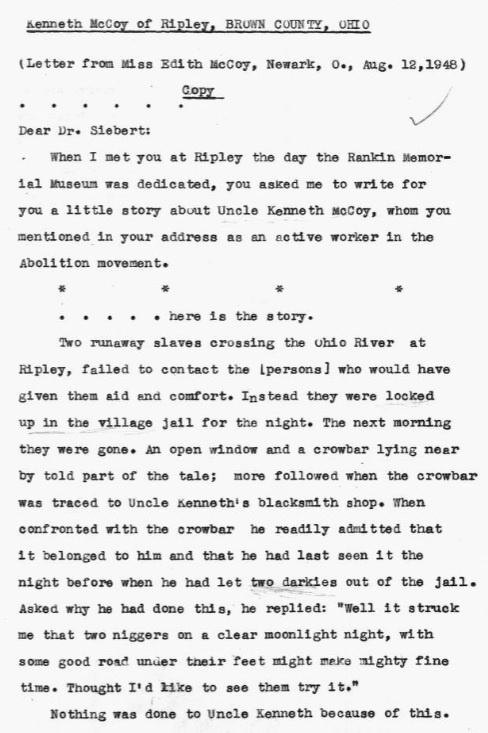

An anti-slavery society was organized along this "underground line" through Greene County, the general place of regular meeting being at the home of Kenneth McCoy, near Burnsville. His home, one history book states was the next station after leaving Mr. Leonard's in Greene County.

The transfers of refugee slaves northward were made by night. A large cellar at Mr. Leonard's was used as a hiding place.

An important station along another underground tributary was the still standing, stately stone Thomas Hughes dwelling in Jefferson, which ironically enough, was built by slave labor in 1814.

The leading members of the anti-slavery society here are said to have been John Henderson, James and Alexander Sprowls, Robert and Isaac Sutherland and John and Kenneth McCoy.

It is surmised by modern historical followers that the under-utmost secrecy, since most of the Greene County residents were native Virginians, who learned, by family custom, toward the pro-slavery policy. Greene County would, however, have already been classified as a slavery area, for as early as 1820 there was a total of only seven slaves in the county.

Following are some Underground Railroad incidents taken from the "History of Washington County" edited by Boyd Crumrine.

"In spite of terrors of the fugitive slave law, there were bold men who did not hesitate to become station agents of the Underground Railway, which had several routes across Greene County.

"The roadway of this camp was not alwys the same though stations and agents were always to be found.

"The fugitives from Virginia, on the south, seldom came down the Monongahela River, perhaps because that was the route which they would be expected to follow. Instead they always traveled with guides across the country, along unfrequented ridges and valleys until brought to friendly stations."

"In 1856," the history continues, "a half dozen slaves escaped from their owner near Clarksburg, W.Va., under the guidance of an experienced conductor. On arrival in Waynesburg the slaves were delivered over to a colony barber, Ermin Cain, who fed them at a spring in a deep thicket across the creek, then brought them to a drying house, where he hid them among the lumber.

"When the slave owner and possee approached they were moved to the Rogersville region for greater safety.

"The barber met the owner who charged him with a knowledge of his property. The barber trembled but while the owner threatened, coaxed and scolded, the barber parlayed, joked and denied to gain time for the fugitives.

"At length the owner offered him $300 each for the slaves, but the barber rejected by saying, No Sir, if I knowed where your slaves are, all the money in the South wouldn't get me to tell.

"The slaves were not found.

"They were shipped from Rogersville to West Alexander, thence to Middletown and then when the owner's watch ended, they were cautiously slipped back to Washington into the care of Samuel W. Dorsey, a colored barber in Washington, who well knew how to get them into Canada."

Freedom Seekers' First-Hand Accounts of the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad Records: Narrating the Hardships, Hairbreadth Escapes, and Death Struggles of Slaves in Their Efforts for Freedom

Modern Library writes of its publication of William Still’s 1872 rare account of Freedom Seekers’ experiences, the book is “A riveting collection of the hardships, hairbreadth escapes, and mortal struggles of enslaved people seeking freedom: These are the true stories of the Underground Railroad . . . As a conductor for the Underground Railroad—the covert resistance network created to aid and protect slaves seeking freedom—William Still helped as many as eight hundred people escape enslavement. He also meticulously collected the letters, biographical sketches, arrival memos, and ransom notes of the escapees. The Underground Railroad Records is an archive of primary documents that trace the narrative arc of the greatest, most successful campaign of civil disobedience in American history. This edition highlights the remarkable creativity, resilience, and determination demonstrated by those trying to subvert bondage. It is a timeless testament to the power we all have to challenge systems that oppress us.”

Pathway Toward Hope, Possibility, and Courage

Dispelling Myths and Misconceptions about the Underground Railroad

Sometimes when people tell the story of the Underground Railroad what they imagine, and what some early scholars depicted in their own work, was a network made primarily of benevolent white abolitionists who helped escaped slaves who couldn’t help themselves. And while there were many white abolitionists who were absolutely involved in the system, sometimes this story can lead to many people ignoring or erasing the fact that it was mostly Black people who were a part of, and who led, the Underground Railroad’s efforts.

~ Clint Smith, The Underground Railroad: Crash Course Black American History #15

You must be logged in to post a comment.