Gallery with alias: PUBLIC_HISTORY_BLOG_POSTS not found

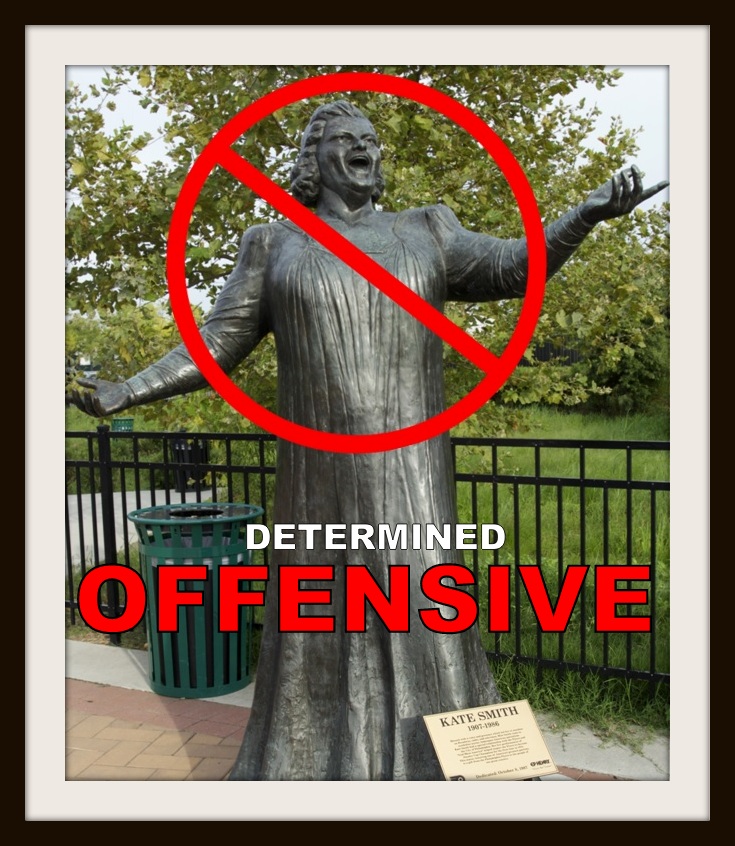

“We have recently become aware that several songs performed by Kate Smith contain offensive lyrics that do not reflect our values as an organization,” read an official statement from the Philadelphia Flyers sports organization. “As we continue to look into this serious matter, we are removing Kate Smith’s recording of ‘God Bless America’ from our library and covering up the statue that stands outside of our arena.”

And just like that it seems, after decades of respected and celebrated status, the legendary singer and icon of American patriotism (recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom) and daughter of the South (born in Jim Crow era Virginia), is banished. Determined offensive.

The Flyers’ so-called discovery of racist song lyrics sung by Kate Smith calls into question how we choose to live with both historic past and present. Some say, that was then, but this is now. Others assert, let the past stay in the past. Yet others warn: never forget; the past is prologue.

After years of reverence given to Smith by sporting teams (e.g., Philadelphia Flyers, New York Yankees) and countless other organizations that use her incredible rendition of “God Bless America” to begin or end their events (including veterans functions such as Pittsburgh’s Veterans Breakfast Club), this newly found outrage over Smith’s past seems reactionary.

THAT WAS THEN. THIS IS NOW

Certainly, Kate Smith’s racist song lyrics (also known to have been sung by legendary black civil rights icon Paul Robeson), are not acceptable in our time. But, some would argue, they were of “her time.” It’s all about judging history by context. That was then, but this is now.

“Back then” in Smith’s time (“That’s Why Darkies Were Born” [1931], “Pickaninny Heaven” [1933], “Mammy Doll” [1939]), popular entertainment was awash in white-motivated, de-humanizing depictions of African-Americans. Although it has been suggested without much empirical evidence that the song appeared in George White’s Broadway revue Scandals as satire intended to ridicule white attitudes towards blacks, the song could have equally been a cheeky lampoon of the black experience or perhaps the whitesplaining of black lives to white audiences.

Despite the popularity and acceptance of these stereotypes in old films, radio shows, and hit songs, not everyone “back then” was accepting of the sambo, golliwog, coon, mammy, pickaninny, stepin fetchit, and minstrel characters, In fact, there were active and morally correct anti-racism social movements speaking up and against them. Social leaders such as W. E. B. Du Bois, the NAACP, Jane Addams, and William Monroe Trotter were disgusted and outraged by these stereotypes, just as many are outraged by today’s hurtful black stereotypes of the the black bitch, welfare queen, thug, and gangsta nigga.

In reality, throughout our history African Americans have been respectfully and accurately portrayed in popular culture. But black social justice activists (e.g., Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, Paul Robeson, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and James Baldwin) have alerted us to our racial myopia and careless acceptance of how black people have been negatively represented in other instances. For their efforts challenging these images fostered by certain white-dominated social, political, and economic orders of the day, they too were openly mocked and stereotyped as, shall we say, dangerous “uppity niggers.”

HISTORY IS NOW

Today our awareness and sensitivity around such things is evolving. Calling out expressions of racism in Kate Smith songs and Philadelphia Flyers hockey games (for perhaps abetting racism even if unknowingly) is bound to be controversial–and sometimes slow to coalesce. Representing the activist group Black Lives Matter, Asa Khalif responds, “The Flyers knew about Kate Smith’s history and her racist lyrics . . . We are surprised it took the Flyers this long to catch on.” He notes that BLM had been alerting the Flyers about Smith’s songs for more than a year. “We are glad they had the courage to [eventually] stand up to racism and anti-blackness, and took the bold move to cover the racist statue,” Kalif said.

This view, we think, will not sit well with many people. We know that honest, open, and critical discussions about history oftentimes conjure up controversy, contradictions, and contentions. History is not determinate; instead it is determined by a confluence of facts, opinions, and competing values.

History itself always exists on contested cultural terrain; to pretend otherwise is to accept what too many 5th grade history books still assert: history is about the past, and the past is over and done with. At The Social Voice Project, we believe that history is always now, in the present, ongoing, making and remaking itself with each new generation that chooses to accept, reject, praise, lament, or make use of the historical record to inform who we are now and in the future.Was the Civil War about preserving slavery or stopping succession? Does the Mississippi state flag represent Southern heritage or cultural racism? Does playing Kate Smith’s version of “God Bless America” at a hockey game tacitly condone racial bigotry?

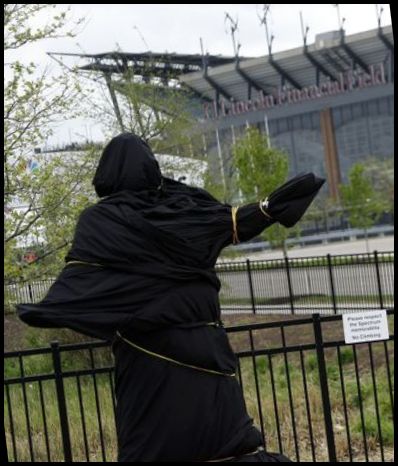

As of this writing, in response to this issue the Flyers have cloaked in black fabric Kate Smith’s celebrated statue standing outside the Wells Fargo Center—which raises the question, can we erase or remedy our historic past by covering over our present?

This post is inspired by an online article published in The Inquirer on April 19, 2019: “Flyers cover Kate Smith statue, dump ‘God Bless America’ over past racist songs,”by Rob Tornoe.

PUBLIC HISTORY MATTERS

At The Social Voice Project, we celebrate history and people through our community oral history projects that give us a chance to look, listen, and record the voices and stories of our time. We encourage all local historical societies and museums to capture, preserve, and share their communities’ lived experiences, memories, customs, and values. Future generations are depending on it.

Contact TSVP to learn more about our commitment to public history and community oral history projects.

You must be logged in to post a comment.