Little Beaver Historical Society Podcast

Northern Beaver County Farming & Agriculture

History

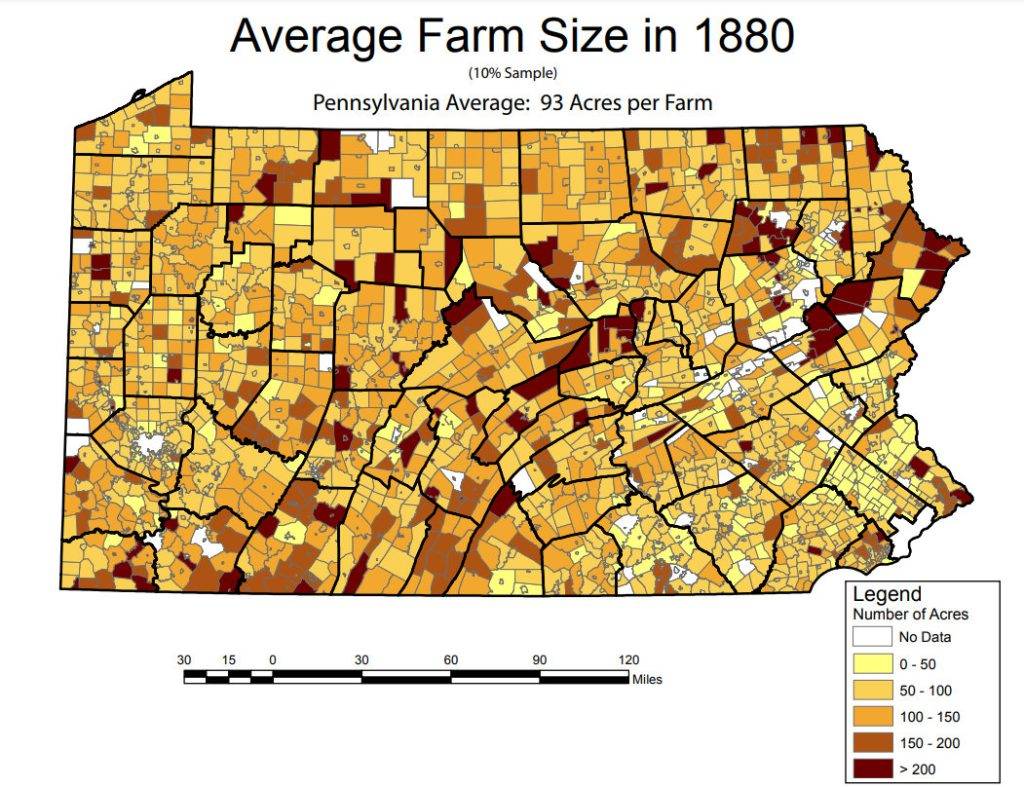

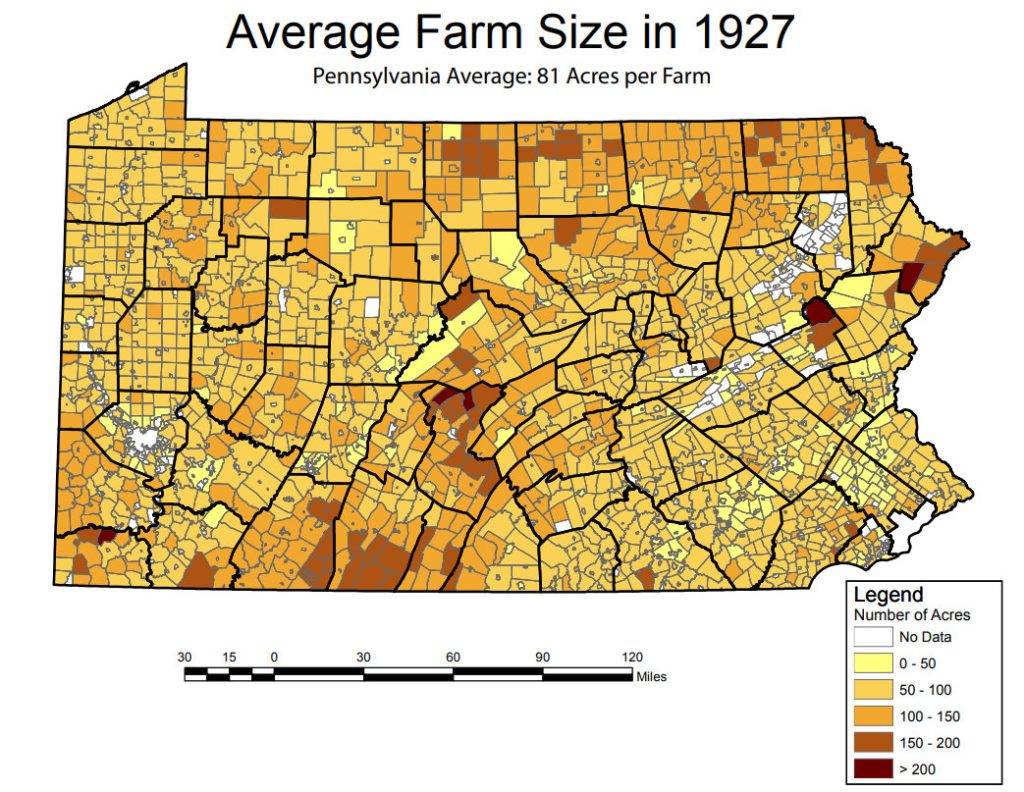

Early Beaver County Farming Communities - By the Numbers

Source: Pennsylvania Agricultural History Project: Historic Agricultural Resources of Pennsylvania c 1700-1960

Feature: Farm Machinery

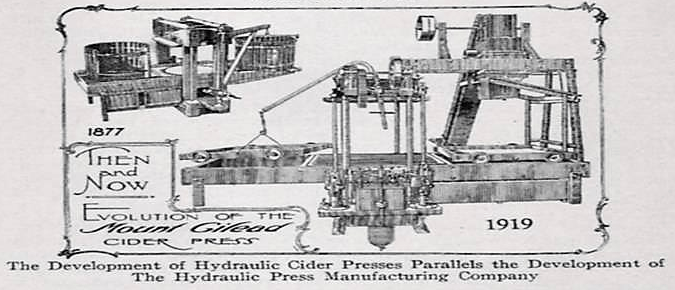

“MAKING CIDER, 1919”

Frank Steele grew up on a farm near the intersection of Blackhawk and Georgetown Roads in South Beaver Township. According to LBHS historian Charles Townsend, “Frank wrote his memories by hand in a loose-leaf notebook sometime during the 1970’s when he w as in his seventies. My late cousin, Peg Townsend, who lived in the house of Mr. Steele’s grandparents, William and Susannah Smith, built in 1908 after their log cabin burned, provided me with the copy.” Here is Mr, Steele’s account of cider making:

My father bought a cider press from Lutz Brothers of Chewton, Pa. for $75.00. The press was a Mount Gilead Hydraulic 30 inch, and was run by a four horse power Detroit, one-cylinder engine. We did not have enough power. I had a 1914 Buick (that) I took the body off and put a 24 inch pulley on the drive shaft, and it really made the press hum. About everyone going by stopped to watch the old Buick. Howard McCreary sold Buicks in Beaver Falls (and) he brought out a Buick factory man to get pictures of it.

My father bought a 8-16 International tractor from Joe Court about 1919 (and) he also bought a (larger) cider press, 36 inch, from Tom Madden about 1922 for $100.00. We could press 2 barrels of cider at one time. It was operated with the tractor. We would make from 40 to 50 barrel a day on the large press. I sold the press to Mr. Rupert, near New Waterford, Ohio, in 1939. We charged one dollar a barrel for making cider.” (About $17 in today’s dollars).

Source: LBHS Facebook post, October 20, 2020.

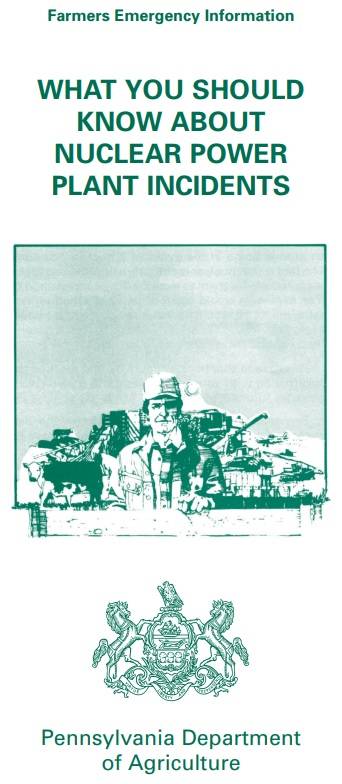

Feature: Farming in the Shadow of Nuclear Power

IF AN ACCIDENT OCCURS

Feature: Rural Journalism

Historical Reflections by Sam Moore

Sam Moore grew up on a family farm in South Beaver Township, Pennsylvania during the late 1930s and the 1940s. His official bio states, “Although he left the farm in 1953, it never left him.” Now retired, Sam continues to tinker with old tractors, peruse and collect old farm literature, and write about old machinery, farming practices and personal experiences for Farm and Dairy, as well as Farm Collector and Rural Heritage magazines. He has published one book about farm machinery, titled Implements for Farming with Horses and Mules.

Farm and Dairy celebrates its 110th year as our region’s locally focused daily agricultural news source. The paper, now available online but still printed and distrubuted to newstands throught Beaver County and surrounding communities in Ohio and West Virginia, is a useful service, writes its family owners-publishers: “We have never lost sight of providing useful, timely and valuable information to our readers and, in turn, offering our advertisers a loyal, defined audience in order to market their products.”

In addition to current agricultural news and market reports, weather forecasts, and farm auction listings, Farm and Dairy also reflects and celebrates our rural Appalachian folkways–from local history and lore, human interest stories, homestyle recipes, to down-home blue-grass entertainment.

For many years Farm and Dairy reserved space for Sam Moore’s “homegrown” stories and reflections about rural life in northern Beaver County and beyond. Some of these stories have been preserved and presented below.

Sam Moore's Most Memorable Homegrown Stories

Tractors by Sam Moore

To readers of the Beaver County, Farming in South Beaver page, the following is taken from the first “LET’S TALK RUSTY IRON” column I wrote for the Farm and Dairy. It was published on the 7th of May, 1992.

This column is a new venture for me. The Farm and Dairy has been looking for someone to write about old farm machinery and tractors, and asked me to give it a try. I’m not an expert on “Rusty Iron,” but I have accumulated some, and I’m interested in the history of the development and evolution of these machines. The column, then, will be about the antique tractor and implement collecting hobby and farm equipment history, along with a little about the shows I attend.

I grew up on a farm in South Beaver Township, in Beaver County, Pennsylvania, during the late ’30’s, the’40’s, and the early’50’s. As a kid, fascinated by machinery and tractors, I collected a thick scrap book of tractor and machinery ads and sales literature. It’s a pity that scrap book wasn’t saved. My earliest memory of a tractor goes back to about 1936 or 1937. My father, Sam Moore, and my uncle, Chuck Townsend, were partners in running a three hundred acre farm belonging to my grandfather, Sherman Moore. For power, they had a team of horses, named Ted and Polly, and an old, gray, McCormick-Deering 10-20 tractor. I remember riding on the platform, holding on to a fender for dear life, while the old 10-20 jounced and vibrated along on steel lug wheels.

About 1939 the 10-20 disappeared and a used, red, Farmall F-30 on rubber tires took its place. I was crazy about this tractor and longed to drive it, but my legs were way too short to reach -the clutch. At first, we pulled the old two bottom McCormick-Deering plow we’d used with the 10-20, but later got a three bottom, John Deere, truss frame plow, with rubber tires. The big Farmall and three bottom plow made quite a rig in our area, since our neighbors all had smaller, one or two plow tractors, or none at all.

In the spring of 1941, the horses were sold, and to replace them, a Ford-Ferguson tractor, two bottom plow, and two row cultivator, was purchased new. At last, a tractor I was sure I could handle!

Immediately, I started hounding Dad to teach me to drive, and finally, he let me operate the little Ford. I was about eight years old and was in heaven. About three years later, the partners got another new Ford-Ferguson and sold the Farmall, so I never did get to drive it. Right after this, the partnership was dissolved and the land and equipment divided. Dad ended up with the newer Ford, which we used until he gave up farming in 1953.

Dad moved to Salem, where he managed the Salona Supply Company for many years, and I didn’t have much to do with farming during a career with the Ohio Bell Telephone Company. As I grew older, I developed a hankering to own an old tractor and, about five years ago, I got my first, a 1941 John Deere H. I now have eleven two-cylinder John Deere tractors, ranging in age from 1938 to 1956, in all stages of restoration, or lack thereof. I’ve also got a nice 1948 Case S tractor and a 1951 Oliver Cletrac crawler tractor that doesn’t run. I have four or five John Deere drag plows, a 1948 John Deere 12A combine, that I hope to use this summer to cut wheat, and a John Deere Number 5 tractor mower from the late’40’s that is used to cut weeds. I’ve almost completed restoring a 1930 Case-Osborne horse drawn mower, and have an Emerson-Brantingham-Osborne mower from the 1920’s, and an International Harvester Company-Osborne mower from the late teens, that I plan to restore. A future column will explain why all three of these highly competitive companies built Osborne mowers. Next time, I’ll talk less about me, and more about “Rusty Iron.”

Farm Trucks by Sam Moore

The following is taken from the “LET’S TALK RUSTY IRON” column I write for the Farm and Dairy.

On a recent trip to western Ohio, Nancy and I stopped at a 76 Truck Stop to take a break. I picked up a copy of the May issue of Truckers/USA magazine containing a great piece titled “Days Gone By” with pictures of many antique trucks. I drove a dump truck for Tommy Ferguson for a couple of years before entering the Army in 1953, and trucks have always had a special appeal to me.

We always had a truck on the farm when I was a kid, although they were strictly for field use and were never inspected or licensed for the road. The first one I remember was an ancient Dodge Brothers flat bed that Dad reroofed with oil cloth and painted bright red with a brush. About 1942 it was sold and a 1936 Chevrolet 1 1/2-ton flatbed took its place. The trucks were used for hauling hay and unthreshed grain from the field to the barn and coal from a mine at the back of the farm. Sometime during the war we got a hayloader and I was deemed old enough to drive the truck, pulling the loader, while Dad and my uncle built the load. Once, I remember Dad jumping over the cab, onto the hood and then onto the ground, because a blacksnake had come up on the hayloader.

I built a box-like backrest from boards to brace me up in the seat far enough to reach the pedals and see out the windshield. I thought I was really something, and only wished I could get that old truck out on the road so I could put it into fourth gear; most of my driving was in creeper gear.

Many farmers in the neighborhood had trucks, often in place of a family car. I remember an early’30s Reo Speed Wagon pickup (Chuck Townsend), a ’29 Ford AA flatbed (Herb Cowan), a ’38 Ford cab over engine flatbed (Harold Smith) and a ’36 IHC pickup (Mr. Shuster).

Farmers recognized the usefulness of trucks early in the 20th Century and, during the teens and ’20s, many tractor manufacturers also got involved with motor trucks. Two of the more famous, Ford and IHC, continue to build trucks to this day.

A 1908 ad aimed at prospective dealers, for the International Harvester Company’s International Auto Wagon, claimed “Every businessman or farmer in your vicinity is a prospective customer.” In pictures, the vehicle resembles a light wagon with a seat and steering wheel at the front, the engine being mounted under the machine. IHC continued to build trucks of every size and shape; in 1979 it was the leading North American producer of medium and heavy trucks. By the mid-’80s IHC was in serious trouble, selling their farm equipment division to Tenneco in 1984, and then forming the Navistar Company to build trucks.

After two years of testing, Henry Ford began producing trucks in 1917 with the one ton Model TT. This machine was especially popular with farmers for the same reasons as the Model T car, low cost, dependability, and ease of repair. Until the late 40s, Ford built only light and medium duty trucks, although in 1926, several experimental Fordson 3-ton trucks were built. These were of cab over engine design and a picture shows a radiator, identical to the Fordson tractor, sticking out beneath the windshield about a foot. In 1948, Ford began building their F-7 and F-8, 2 1/2- and 3-ton models, and continue to make light, medium and heavy duty trucks today.

The Advance-Rumely Thresher Company built a sturdy 1 1/2- to 2-ton truck from 1919 to 1928. In 1925 the machine sold for $2200, not including a closed cab, pneumatic tires, or electric starting and lighting equipment.

The Twin City truck was built by the Minneapolis Steel and Machinery Company beginning in 1918. The company made 2- and 3 1/2-ton versions until 1929.

The Avery Company began building a 3-ton “Country and Farm” truck in 1914, with chain drive and special cast steel rim wheels designed for rural hauling. Avery’s last trucks were 6-cylinder jobs, equipped with an “all weather cab” and a 50 by 90 inch grain body, capable of hauling 1 1/4 tons. Production of Avery trucks ended in 1923.

The Samson truck was built along side the Samson tractor in Janesville, Wisconsin starting in 1918. The Janesville Machine Works was a subsidary of General Motors and only built Samson trucks for a few years. A 1919 model was priced at $995 plus “war tax”.

The Moline Plow Company sold a few trucks from 1920 to 1923, while Velie trucks and cars were sold through Deere and Company distributors in the teens. Oliver built the Oliver Delivery Wagon from 1910 to about 1913.

In the days of horses, farmers living 15 to 20 miles from a good market had a real problem unless a railroad ran nearby. A team and wagon required most of a day to make the round trip to town and back, and in hot weather, were often unable to make the return trip till the next day. A truck could cover 20 miles in a couple of hours and was always ready to go.

In 1915, an estimated 25,000 trucks were on American farms and, by 1930, the number had grown to 800,000. One result of the farmer’s extensive use of motor trucks was the growth of central market places in large urban areas. Small towns that, in the days of horses and railroads, had been the trade and social centers of their areas, withered and faded into obscurity.

Remembering the Days When Small Tractors Did It All by Sam Moore

When I was a kid during the 1940s, my grandfather owned two adjoining farms in western Pennsylvania totaling about 300 acres. Much of the land was taken up by woods, pastures, and orchards, and I suppose we actually raised crops on less than half of that acreage. Most of the farms around ours were probably about 50 to 150 acres.

Virtually every one of those farmers had a single tractor with which they did all the work required, although a few supplemented the tractor with a team of horses. When I think of those tractors, I’m struck by how much work was done with relatively tiny machines, at least when compared to today’s monsters.

The Ford-Ferguson my family acquired in about 1944 with my cousins, Peggy and Chuckie Townsend. This photo was probably by their father, Charles Townsend, who was in partnership with my dad.

I remember a Fordson in the neighborhood, plus a couple of Allis-Chalmers WC’s and several A-C B’s and C’s. One of the larger farmers had horses and a Farmall F-20, which was later replaced by a Farmall C. There was a Farmall H or two and one Farmall A. On our farm, we at first had a McCormick-Deering 10-20 and two teams of horses. A Farmall F-30, which was a big tractor for the area, replaced the 10-20, and sometime during the early ’40s, the horses were replaced by a Ford-Ferguson tractor.

Wrangling implements on a single tractor

During the 1940s, many farmers managed with a single Allis-Chalmers C (21hp), Farmall H (24hp), John Deere B (18hp), or a Ford-Ferguson (17hp). Hardly anyone had more than one tractor, meaning that mounted implements, such as cultivators, mowing machines, and buck rakes had to be wrestled on and off the tractor several times during the summer as requirements changed.

That was one reason our little Ford-Ferguson was so handy. As the 3-point hitch plow or cultivators took only a few minutes to attach or remove, even a boy like me could do it. The mowing machine was a different matter, however. At some point, we retired the old horse-drawn mower with a cut-off tongue that we’d been using and acquired a brand-new Ferguson agricultural mower.

That mower was a bear to put on. According to the sales literature, the mower “can be taken off or put on quickly and easily, by means of simple connections to built-in brackets on tractor rear axle.” Right! To mount the mower, the 3-point hitch lift arms had to be first removed, and then the heavy mower had to be maneuvered into position so it could be attached to the axle brackets. The lift chain was then hooked to the left hydraulic lift arm, and the PTO connected. At least, the mower could be left in place while using the buck rake, but it had to be removed in order to cultivate.

How big can they go?

The tractor horsepower race began in about 1950 and has continued pretty much unabated for the past seven decades. Farms kept getting bigger, requiring ever-larger implements, which in turn required more power to pull them. The big boys in 1950 were the Massey-Harris 55 with 52hp, the Minneapolis-Moline G with 47hp, the McCormick W-9 with 44hp, and the John Deere R with 43hp.

In 1957, the Steiger brothers built a four-wheel drive, articulated tractor in Minnesota that had a 238hp Detroit Diesel engine. Deere’s 8010 diesel of 1959 had a 215hp Detroit engine.

International Harvester trumped everyone else in 1961 with the 4300. Powered by an IH-built, 300hp turbocharged diesel engine, and equipped with four-wheel drive and steering, the 4300 was the most powerful wheeled agricultural tractor until then.

Unfortunately for IH and Deere, the mass market wasn’t quite ready for such expensive and high horsepower tractors. Through the 1980s, most tractors were between 100hp and 200hp, although each manufacturer offered a line of small machines, many of which were built in Japan.

Today, Case-IH offers the Steiger 620, a four-wheel drive behemoth with a 680hp CIH 12.9-liter engine, available on wheels or tracks. The 620 weighs more than 30 tons with ballast and has a 470-gallon fuel tank, plus an 85-gallon DEF (diesel exhaust fluid) tank. Just imagine filling that tank every day with diesel fuel selling for almost $3 per gallon, while DEF is around $3 to $5 per gallon.

Deere has a 620hp tractor as well, the 9R Series. These big boys, also available in four-wheel and four-track versions, are powered by a Cummins 14.9-liter engine and tip the scale at about 30 tons.

Today’s tractor delivers power – and comfort

No more Arctic Carhartt coveralls, ear flaps and two pairs of gloves while picking corn, or dripping sweat and getting sunburned while baling hay! The operator’s cabs on these beauties are safety glass-enclosed for 360-degree visibility, insulated and soundproofed for quiet running and shirt-sleeve weather year-round. The driver’s seat is as comfortable as your favorite recliner in front of the TV, and usually an additional passenger seat is furnished as well, while a handy lever at your right hand controls speed, gear ratio, and other functions. With GPS controlling the tractor’s direction, and all this comfort, it’d be difficult not to doze off while crossing a long field (I have been known to go to sleep while cultivating corn, much to my father’s disgust at the number of corn plants I took out, and that with no climate-controlled cab and a hard tin seat).

Now the Association of Equipment Manufacturers reports that four-wheel drive tractor sales are down 15 percent this year, while those of smaller machines, under 40hp, have risen by 8.7 percent. I don’t know if this means the tractor horsepower race is coming to an end, or if the high cost of the giant machines along with the price of fuel is having an effect.

Hmmm; I wonder if, in 2099, a well-restored John Deere 9620RX will be some tractor collector’s pride and joy.

When Farmers Were Spotters: Farming the Homefront During World War II by Sam Moore

To borrow from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: Hardly a man is now alive, who remembers … the airplane spotters of early World War II.

During the early 1940s, U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) officers had seen how effective the British Aircraft Warning Service was against the German Luftwaffe during the Battle of Britain, and wanted to organize a similar program in this country. A volunteer civilian observer corps could not only save millions of dollars, but also free up military manpower for use on the battlefronts.

A 1942 field manual states that “the A.A.F. Ground Observer Corps (GOC) is an essential part of air defense” and “the volunteer civilian observers who staff the (GOC) are appointees of the Fighter Command of the Army Air Forces, reporting directly to the Army and under Army supervision.”

The mission of the GOC was to track all aircraft within a predetermined area so that the USAAF would have notice of enemy aircraft before substantial damage could be inflicted by bombing or strafing. Of course, it wasn’t enough to just spot aircraft: Each sighting needed to be identified as to number and type; single or multiple engine; bomber, fighter or transport; friendly or enemy; and include direction of travel and altitude, if possible.

Manning the observation post

When I was a kid, my grandfather owned two adjoining farms south of Darlington in western Pennsylvania. My family shared the larger farmhouse (which was built by my great-grandfather in 1850 to replace a log cabin) with my grandfather and grandmother. The Townsend family lived in the smaller house on the other farm and included my aunt, uncle and older cousin, Peg.

The GOC was organized by the USAAF before the Japanese attack on Hawaii on Dec. 7, 1941. Peg Townsend recorded in her diary on Oct. 4, 1941: “We had a meeting about the observation post. They said it is a sure thing that we will have bombings soon.”

The Townsends had volunteered to host an observation post (OP) and it was established in the front room of their home. The OP wasn’t elaborate, just a small table holding a telephone (on the party line, of course), a set of binoculars, a pad of “flash message forms” and a book full of instructions on identification of the various airplanes one might see overhead. This book contained both photographs and silhouette drawings of all known warplanes of U.S., British, German, Italian and Japanese air forces, and was fascinating to a small boy like myself.

Standard procedure

When an observer saw or heard an airplane, he recorded as much information as could be ascertained about the craft on a flash message form. This included the number of planes, the model (if it could be determined), number of engines, altitude, whether actually seen or just heard, OP code name, direction of plane and distance from the OP, and direction the plane was headed. Thus, a typical message might read: 3 B-17s, high, seen, Code N, SW, 1, E.

That information was immediately phoned to an Army Filter Center, where it was plotted on a big board containing a map of the area. The information was compared to other reports and the plotted flight path was checked against known Army, Navy and civilian flights. The officer in charge then determined if the flight was friendly or enemy and, if the latter, ordered a response in fighter planes or anti-aircraft fire.

Filter centers were run by the Army Air Forces and staffed by both military personnel and civilian volunteers. The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) provided many of the military plotters. OPs and filter centers were known as the Aircraft Warning Service (AWS), a loose alliance of the local civil defense authorities and the military.

Breaking into the party line

In our case, we didn’t have dial phones, so the first order of business was to see if the party line was clear and if not, to break into the conversation with the information that this was an emergency call. When the operator answered, the caller said, “Army Flash,” and gave his phone number, upon which the operator connected to the tracking center (which was probably in Pittsburgh, although I don’t know for certain). They answered with “Army, go ahead please,” and the observer said, “Flash,” read the message and the job was done. I remember one day when my aunt allowed me to phone in a sighting: Boy, was I proud!

In a diary entry dated June 26, 1942, Peg wrote: “Today we received word by mail that our O.P. must go on 24-hour duty at 8 a.m. on Monday, June 29.” Then, on June 29, she noted: “We went on O.P. duty at 8 sharp this morning.”

Of course, our two families couldn’t keep up a 24-hour watch for long, so several neighbors were recruited to take turns manning the binoculars. On Jan. 3, 1943, Peg recorded: “Sunday. Two neighbors came as observers. Got 25 armbands for observers yesterday.”

Blue armbands with embroidered gold wings supporting a white round Aircraft Warning Service insignia were issued to each observer. Small, silver wing pins and merit badges were issued as well.

Serious business

Although the AWS may have had a certain feeling of make-believe in western Pennsylvania, most of the observers seem to have taken their duties seriously, at least at first. It was even more important on the West Coast and in Hawaii, where there was real threat from Japanese planes.

Actually, even in the West, there were very few enemy air raids against the U.S.: Enemy planes just didn’t have the range necessary to reach our shores. In October 1943, the GOC and the filter centers were taken off 24-hour basis and put into reserve, being activated after that only occasionally for tests and training, and completely deactivated on the continent in 1944 (I believe they continued on the Hawaiian islands until V-J Day).

The GOC had a song based on the Army Song, but all I remember of it is the line: “For it’s one bi high, and another we will spy, and call in our numbers loud and strong. …” There was a prayer, as well, that went: “Oh Lord, give us the ears to hear, the eyes to see, that Zero if he tries to hide among the clouds. And if he does come, give us the heart to forgive the poor misguided soul who holds the phone for insignificant gossip while we try in vain to get the warning through. Forgive the man whose time is all absorbed with pleasure, who can not find time to help us keep the watch, who sleeps complacently in the wee small hours of the morn while we must stand in the icy wind and rain on guard that he may sleep. Please find a way to give us just one more cup of coffee, just a little piece of meat or just another gallon of gas, but if there isn’t enough to go around, then give it all to our fighting men and just pass us the beans. We, too, can take it.”

The GOC was a good example of how nearly everyone was involved in the war effort in some way during World War II. My father was an air raid warden, and we kids collected tin foil and scrap metal and, in the fall, milkweed pods for kapok life jackets, and nearly everyone bought War Savings Bonds or Stamps.

Feature: Local History

Farm History from "Milestones - The Beaver County History Magazine"

First Farm Society of Beaver County

Milestones Vol 14 No 4 Winter 1989

Beaver County’s industry and grange groups are a far cry from the early leaders of the rural districts of Beaver County. The first signs of desired organization was the banding together of small “neighbor” groups with similar interests. The Beaver County Agricultural Society was organized after county-wide agitation that lasted almost ten years.

The first meeting was called for a study of varied plans for such a group. An ad just signed “Farmer” appeared in the Argus February 28, 1844 and read as follows: Agricultural Meeting! The farmers of Beaver County are requested to meet at the courthouse, Beaver, on Monday evening the 4th day of March next (court week) for the purpose of forming an agricultural society of Beaver County. It was obvious this meeting was a success, because three months later the same paper carried another ad dated May 22, A meeting of the Beaver County Agricultural Society will be held in the courthouse, Beaver on Monday evening the third day of June next, at which time a constitution will be submitted and election of officers held.

The township committees appointed for obtaining subscribers will be expected to report May 20th. The first elected officers were: William Morton Esq., Chairman; Vice-presidents, Thomas Dugan, Thomas Cairns, James Sterling, and Thomas Nicholson. Secretaries were: Robert McFerren and James T. Robertson. David Minis was Treasurer.

A Real American Idol Celebrates 100th: Mail Pouch

By Jack Goddard

Milestones Vol 32 No. 2

What Beaver County Americana icon is quietly celebrating its 100th birthday this year? Here’s a hint. It’s estimated that a dozen or more dotted our landscape once but now only three are known to have survived time to celebrate its centennial.

They were a favorite for many years to any kid who ever rode in the back seat of a car. Then the government stepped in and ended the romance. They were once so popular that a British salesman, visiting the United States for the first time, was asked by a reporter what our country was famous for over there. Without a hint of hesitation he replied, “Beautiful women and Mail Pouch barns.”

The poor barns are slowly fading away due to neglect, but their popularity to some hasn’t. Enter the Mail Pouch Barn Stormers. This preservation society, headed by Lonnie Schnauffer of neighboring Butler County is making great strides in attempting to save these nostalgic national treasures. The Gibsonia man said he was visiting another “barnstormer” or Mail Pouch barn enthusiast in 2001, Cleve Costly of Ohio.

The latter had already been painting colorful Mail Pouch barns murals on decorated walls at local fairs and festivals. “It was Cleve who pointed me in the right direction,” according to Schnauffer. Cleve introduced Lonnie to the last big-name Mail Pouch barn painter, the intriguing Harley Warrick of Belmont, Ohio. This trio wondered if anyone else had the love they had for these cherished structures.

They decided to hold a picnic to find out. Warnck, however, died in November 2001, just months prior to their first scheduled meeting and picnic in the summer of 2002. “We didn’t have a clue as what to expect now,” Schnauffer pointed out. The North Hills engineer said he and Cleve Costly were “pleasantly surprised” as about 45 people showed up at this grassroots meeting. It just started snowballing from there. “Talk got around, and we had over 70 the next year.” The membership roll’s total is pushing 140 today ———only six years after those three got together.

“We encourage that anyone having an interest in Mail Pouch barns to come to our 2007 annual meeting and picnic at the Belmont, Ohio, school gym. It’ll be held on Saturday, July 28. “Ha,” he asserted, “Just be sure though to bring a covered dish, so we have enough to eat.” Belmont is off I-70, 15 minutes from the state line.

Warrick, up until he retired in 1992, repainted barns in Beaver County, other Western Pennsylvania areas, Ohio, West Virginia and nine other states. When his team would do the work, his initials “HW” would go up on the blue border or in the middle just under the roof. They were put under the overhanging eaves so that they would be protected from inclement weather or the hot summer sun. When he left, the barn-painting program was abolished.

He, with his ever-present pipe, was a popular figure. Warrick, who preferred bib overalls to coveralls, had a fountain of comic anecdotes he’d picked up over the years. For instance, when he was asked what it was like painting in cold weather, he replied with a smile, “We just added more thinner to the paint —- and, maybe a little Seagrams to the painter. It’d then all turn out fine.” Another story had him and his gang painting a barn in the Ohio flat-lands. It was a bone-chilling windy day. A strong gust blew the roof away in splinters. The helpers said, “Well, guess we’re done for the day.” Warrick is said to have bellowed, “Hell no! This wall is still standing.” So, they continued to paint.

Then there was the time when a candy company owner wanted the familiar icon on the side of his manufacturing plant. He bet the men a steak dinner that they couldn’t do it in a day, Barnstormer Elmer Napier says. “Needless to say,” Napier chuckled, “The whole gang enjoyed a steak dinner that evening.”

Finally, there’s this tale. There was a rule that another worker on the scaffold couldn’t touch the painter. If you did you had to buy him a drink. Harley admitted that when he was hot and thirsty, “wanting to wet my whistle, I’d find a way to get touched.” Scott Hagan, another Barnstormer laments, ” sure do miss the guy.” Hagan does some private re-paints in the area, his last being in Marietta, Ohio. “Harley was amazing,” Hagan explained. “He could paint a barn in four hours!”

Hagan said Warrick was his mentor. “He taught me how to do them. We’d size up the barn first and start in the middle, working our way out. For example, the first letter in the “chew” line is “e” then, in the second, it’s the “p” in pouch.” Hagan went on saying that Warrick was milking cows when a gang asked him to join. He had painted in the service so was confident he could do it. Hagan laughed and said Warrick figured it’d, “beat milking cows.”

In the meantime, Warrick had no idea of how much excitement he generated. It was like the recent book, The Five People You Meet in Heaven but in real life. One never realizes, no matter how insignificant the existence led, what an impact it had on us, especially generations of kids who got a free ticket to punch their siblings ———–under their very own parent’s eyes. It didn’t take a lot to keep us happy back then.

After Harley hung his brushes up, so to speak, he still couldn’t get away from the work he enjoyed so much. The happy-go-lucky gent had a fondness for tinkering in his wood shop making Mail Pouch post boxes, bird houses, bird feeders and the like. Although he passed before the initial meeting, this writer is one of many who believe he’s looking down proudly beaming and with a grin ear-to-ear ————probably standing beside a Mail Pouch sign.

We had “mom and pop” stores then. That’s how the Mail Pouch story got its start. Two brothers, Arron and Sammuel Bloch owned a store in downtown Wheeling W. VA. In 1890, they founded the Bloch Brothers Tobacco Company. Swisher International officials announced to this writer that today, they’ve named this branch Mail Pouch Tobacco. They put out over 15 products now in the chewing tobacco and snuff lines.

Swishers International Inc. officials reported that barn painting, the oldest gimmick to advertise Mail Pouch, came to an end in 1965. This was when the government (no surprise here) got in to the act. They, that year, passed the “highway beautification” bill that limited advertisements to being at least 660 feet from the highway. It also helped launch those witty and sometimes humorous red and white Burma Shave signs into eternity. Another killing blow “was times were changing.” Speedy interstates were replacing those roller-coaster-like narrow two-lanners that followed the contour of the land. Fifty miles an hour wasn’t speeding anymore — it was hardly moving!

When Arron began the barn-painting program in 1907, he ordered that a black spot be placed in the center of every foot on the outside yellow border. Why the black spot? Painters were paid by the square foot and a photo of their work had to be sent to the main office so they could get paid and have expense monies reimbursed.

Hagan stated that Warrick, who passed away at age 76 years, was, “by far the most famous Mail Pouch Barn painter.” It is estimated that he painted or re-painted 20,000 barns. “He told me once,” Hagan grinned, “that the first 1,000 were pretty rough, but then I got the hang of it.”

The buildings were re-painted every three or four years. The task was given to local painters at first, as one could travel only by rail or a horse-drawn vehicle. But, as transportation improved, painting contracts were narrowed down by 1933. Now, only a few painters from both the east and west coasts were called upon. Hagan stated that Warrick came on the scene in 1946 after serving a stint in the military. He stayed around 55 years.

Although Mail Pouch was the granddaddy of barn advertising, others tried to capitalize. One named “Wow” gave up in the mid-forties. Others mentioned included, “Red Man” and “Beach Nut.” But, they are a rare find today. The upkeep and sudden interest in Mail Pouch Barns are preserving their existence a little longer.

“Ha,” Schnauffer chuckled, “You could say we were even international for awhile.” He explained, “that one Barnstormer lived in Canada for a time.” He closed, “but we are represented by 17 states now.” He added that the most common Mail Pouch Barn has gold or white letters on a black, blue or red background. The rumor is that red barns are rare since they are harder to paint. Schnauffer though re-painted a red one on Glen Eden Road in New Sewickley township heading north on route 989 to Unionville.

Back to the earlier days. Farmers had the choice of being paid with money, tobacco products or subscriptions to either Collier’s or the Saturday Evening Post.

However, later when barn ownership changed hands, things became quite complicated so farmers were paid cash on an annual basis. But, they were priceless to us kids who grew up with them around. Remember the fun we had? Riding in the back seat peering out an open window and counting them. Burma-Shave signs too. Or, maybe it was brown cows, white cows, calves!

In today’s narcissistic society, I was overjoyed by how Mail Pouch received its unique name. In 1879, the brothers added several women to the top floor of their store where they made fresh “stogies.” Smoking these caught on from people watching burly drivers of Conestoga wagons, from which they were named, roll through going west.

The ends of these “stogies” had to be clipped and discarded. Since most of their customers were miners and couldn’t smoke down under anyway, one of the brothers came up with a bright idea. They decided to make use of the clippings, cover them with a sweet flavor and sell it so the men could chew it. Licorice, the flavor used most during this era, was chosen. It sold quickly and before long it became difficult for the Blochs to keep up with the demand. The entrepreneurs, at the beginning, shipped the material out to wholesalers who would package it with their own brand name on it.

After some eleven years, the Bloch brothers decided that they wanted to package it themselves. It would be more convenient and also make them more of a profit. But, they needed a name. This is the good part of the story. They got everyone involved and urged their customers to jot down catchy titles and put them in a large jar. It’s also important to remember that this was before the telephones and car. The only way for people to communicate then over a long distance was by the United States mail.

The main social activity for many in those years was to congregate near the ‘ol potbelly stove at the busy general store waiting for the mailman. Many would just stand around telling tall tales while others played checkers or cards. The mailman would finally come, not only with the mail, but stories from the neighboring towns and villages. As a gesture of good will, he too was asked to enter the contest. He wrote something down on a piece of paper and dropped it into the receptacle. Finally the big day arrived and the customers all gathered around the bottle. Out came the winning entry.

It was the mailman’s selection, thus Mail Pouch Chewing Tobacco was born.

References: (I thank Swisher International, Inc. for the following very informative information) 1. History of Swisher International, Inc. 4000 Water Street Wheeling, W. VA. 26003 2. How Mail Pouch Chewing Tobacco was named 3. Mail Pouch barn signs (Author is also grateful to Lonnie Schnauffer, Scott Hagan, Don Warrick, and Megan Warrick)

Milk Control Board – Beaver County First in the State

Milestones Vol 14 No 2 Summer 1989

Back in 1928 the Beaver County Commissioners met with the Beaver County Public Health association and agreed to appropriate a sum of money for the financing of a Beaver County board of milk control for a period of two years. With this action Beaver County became the first county in the state to have a countywide milk control board. The state also agreed to assist and this is a first-time for such a state movement. The first members of the executive board were: H.O. Allison, Pres.; Dr. J.B. Reckers, Ambridge, V. Pres.; W.S. Reader, Secretary-Treas.; Dr. Fred Wilson, Beaver-, R.B. Wisener, Midland; Art Coombs, Aliquippa; Mrs. R.W. Soloman, Beaver Falls; Dr. J.A. Stevens, County Medical Director, and Miss Elma Graham, Ex. Secretary, together with Walter Goettman and William 0. Coulter, County Commissioners. Mr. H.E. Shroat of the State Health Department reported on three dairies which he had recently investigated. He stated that from sixteen drops of milk he found 30to 40 million bacteria, whereas the average should be but 300 to 400 thousand bacteria to 16 drops. The County Commissioners are to be commended for this move forward in protecting the consumer and it was through the efforts of the Chamber of Commerce of the upper Beaver Valley that state aid was received.

Zahn Recalls Farms of the 30s and 40s

Milestones Vol 29. No. 4

Russell C. Zahn is an active member of the Big Knob Antique Tractor Club, and anytime this group gets together, they usually end up talking about the way things used to be. Mel Eisenbrown knew that Russ had great recall of interesting farm facts and asked him to speak to the group after a meeting. On Nov. 15, 2002, Russ spoke to the group about the 42 active farms from the Boro of Zelienople to Sunflower Corners between the years of 1930 to 1940. As of today, there are 12 remaining that still till the land. There are also 227 buildings along this same stretch of highway.

1 . Water Zeigler operated The Lutheran Children’s Home and the first tractor they purchased was a Farmall M. The Zelie Sportsman Club purchased the land on the right side of Rt. 68 and is still an active fishing club.

2. Benevue Farm is now being operated as a Bread and Breakfast. BenVenue which means “Welcome Here” was built in 1814 by George Henry Mueller.

3. In this same area there was another farm but the name of the owner is unknown.

4. Jim Steinbach Farm raised Belgian Horses and at one time sold to the Budweiser Co. The first tractor they used to farm with was a Farmall H.

5. Henry Steinbach and Sisters operated a farm on the opposite side of Rt. 68. Since that time it has been operated by George Teets, Art Teets, and now has been divided and is owned by Mr. Belsterling and Lawn Works Inc., a landscaping company. Massey Harris was the tractor of choice for this farm.

6. The Murphy Farm donated ground for Burry’s Church and Roy Young purchased the remainder and the Custard Stand was built.

7. Bernard Farm was located down a lane in this area on the left.

8. The Ed Zinkhant Farm was sold off in lots and they went for $100.00 an acre. This also was farmed by Raymond Zahn and then sold to his son, Harold. They also farmed with a Farmall H.

9. The Forsyth Family now owns The Harry Goehring Farm. This family used the Farmall A.

10. The Oliver Wahl Farm lay on both sides of the road with the house and barn on different sides. This is now the location of Novak’s Junk Yard. They used an Allis Chalmers WC to farm.

11. Henry Wahl Farm has since been owned by Roy Goehring, Ezra Rosenberger, John Pflugh, and now Flynn. An 8 N Ford did the tilling on this farm.

12. Fred Wahl had the farm on what is now Pflug Rd. The road also connected to Willabi Run Rd. They also used an Allis Chalmers WC to farm.

13. Elmer Pflug had the farm at the end of Pflug Rd. and is now the McKinney Farm.

14. Ross Coleman farmed both sides of Rt 68 and it was sold off in lots. Brethauer now lives in the farmhouse. The Allis Chalmers B was the tractor used here.

15. Tom Ault was a sheep farmer and sold the land off in lots. Terry’s Trailer Sales is now located there.

16. Burns Farm was located back Burns Road and now the location of Burns Cemetery. The remainder of the farm was sold in lots.

17. Dan Smith was a teacher for over 50 years and used a single horse to do his farming.

18. Jake Smith hauled the milk for the local farmers to Beaver. His son Larry broke his back in a farming accident and later started Smith’s Gun Shop. Jake also mowed the berms along Rt. 68.

19. Casper Zahn lost his hand in a gun accident and later sold part of the farm to Larry Smith, and his son Ben took over the remainder. It was later sold to Russell Zahn and Bill Kunkle, who established it as a horse farm. The McCormick 10-20 was used to farm.

20. Henry Shaffer died one morning after eating a big breakfast of buckwheat cakes. The farm was sold to Jinkins and they used the Farmall F30. It was sold to George Young and is now farmed by Ralph Young. George farmed with a Farmall H.

21. The Phillip Miller Farm and part of the Jake Smith is where the Legion has been built. Wahl’s Store was not a farm, but it served as the center of the Community. It not only served as a store, but also a feed mill, saw mill, and the first telephone office with operators. In the same store six local farmers started the Farmers Building and Loan.

22. Casper Zahn Farm was established when Ben took over the big farm and Casper bought this and farmed it with one horse after the gun accident. In the farmhouse have lived the families of Freshcorn, VanRyn and now Millers.

23. Albert Lutz Farm was on both sides of Rt. 68 and now the site of the Trailer Court and the remainder sold in lots. A Massey 4-wheel tractor was used.

24. The Orchard Farm was on the left where Chuck Listen and Jr. Landis live.

25. On the Walker Farm the house was built at the point of the hill so the daughter who had TB could have the advantage of the wind and air.

26. Crawford Chaney Farm was sold in lots.

27. Sam Rosenberg Farm had ground on both sides of the road and is now the Bill Ivory Home. He used a Farmall F20.

28. Rotharts Orchard farmed both sides of the road and was sold in lots. There was also a beer joint built on this farm. He used an Allis Chalmers B.

29. Orrin Black’s Farm was a chicken farm, and he had a hammer mill mounted on a car chassis to grind feed for other farmers.

30. Con Boyish was somewhat off of State Rt. 68. The L.C.B. was under the impression that he made moonshine and harassed him often.

31. Kenna Farmette is now the home of George Mengel.

32. John Rosenberger Farm was a dairy farm and also had a large orchard. Carl Young is now farming there. A Farmall. H was used.

33. Slavik Farm had some cattle but was mostly an orchard.

34. Elmer Zahn was a dairy farmer who sold the front of his farm along 68 off in lots. Carl Young now owns the farm. He used a Farmall A.

35. Young Farm was on the right of 68 and is now where Glenn Young lives. They used steam engines to farm.

36. George Rosen was a dairy farmer. The farm was later sold to Martins and is now owned by a veterinarian.

37. The Shaffer Farm was sold in lots that are now called the Shaffer Plan behind Homer Nine Heating. The farm was on both sides of Rt. 68 and John Guthermuth now lives in the old farmhouse.

38. An Unnamed Farm was back off of Rt. 68, and Vargos have built their home in the area.

39. The Sidler House was a small farm. Dave Reader moved the original farmhouse and remodeled it.

40. Spergin Rader Farm is where Beulah Church sits. Mr. Rader was also a preacher.

41. The Shaffer Chicken Farm is now the Schweinsberg farm. When Russ was a kid his family bought pullets from them.

SIDENOTES

Back in the old days, almost every farmer would raise 3 or 4 pigs for slaughter in the winter. The hams, shoulders, and bacon were hung and smoked with hickory or apple wood. Once smoked, they were laid out and covered with salt for a couple weeks to cure them. They were then placed in bags and hung in the granary until they were covered with a layer of mold. The remainder of the pig was made into sausage. It was stuffed into casings or made into patties, fried and then placed in jars for cold packing. The sausage was often served with the traditional self-rising buckwheat cakes until March or April. The hams and shoulders would be sliced and fried all summer long. The head meat and livers were made into liver pudding and also eaten with the buckwheat cakes. Since Bill Allman and Cliff Teets each had 13 children, they probably raised more than the average 4 pigs. The average farm also had at least a dozen apple trees, and in the fall a kettle of apple butter was made. It went well with their homemade bread. Apple cider was made and stored in barrels in the cellar. The sweet cider was enjoyed by all, but after time it turned hard. Once hard, bungs were placed in the barrel and the adults enjoyed the ” high” effect they received from it. If the bungs were left out of the barrel, the cider would get a “mother mase,” and the cider would become vinegar. The vinegar was used for the rest of the year.

Back in thirties and forties, the auto had become a common means of travel. From 1942-1945, because of the war, the manufactures were not permitted to build new cars because the materials were needed for building war equipments. The Nash was the only car built during this time, and these were strictly for the rural mail carriers.

The Mount Pleasant Hillside Farm

By Myrl C. Gilchrist

MILESTONES VOL. 7 NO. 2–Spring 1982

The present house at 908 Western Avenue, Brighton Township in Beaver County was built by John Wolf Jr. in two stages. He acquired the land in 1805 for a fee of $10.63

The bricks used in this structure were made on the location. The right portion, as viewed from the front, was built in 1808 and consisted of one room — used as a living room, dining room and kitchen. A large hall with stairs leads to a small hall bedroom and a large bedroom directly over the living room. Another stairway leads from the upper hall to a large lathed and plastered attic.

The living room-kitchen had a large open fireplace with cranes and other devices for suspending cooking vessels over the open fire. This fireplace was sealed when a central (hot air) heating system was installed in later years.

The hewn joists used for the first floor of the initial project were believed to be taken from Fort McIntosh. (John Wolf Jr. had lived in a part of the old fort while he built or helped build houses in Beaver.)

During a second construction phase what is now called the parlor was built with a large bedroom above. The hewn joists for the first floor of this part were also taken from a part of the fort.

The fireplace in the “new” part is a device manufactured with cast iron shaker grates, steel dampers and ornamented cast steel enclosure parts. The firebox is lined with fire tile. This device is in one piece and can easily be moved out of the chimney opening for cleaning or repair. Most likely this was a large open, log-burning fireplace originally and equipped later with the present more sophisticated device. An open fireplace also exists in the second floor bedroom.

Flooring for both parts of the house consists of tongue-and-groove random width boards a full one inch thick. Where the floor boards meet end to end they are cut at a forty-five degree slant. It is believed by some authorities that the flooring is of cucumber wood.

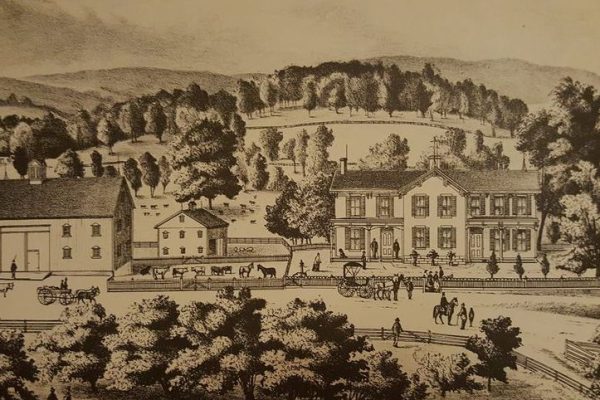

An artist’s sketch in Caldwell’s Beaver County Atlas published in 1976, shows a tiny front porch and a replaced by a frame addition, also two stories high. This original house. It is known that at one time a dug well existed at a point near the center of the present kitchen.

The back door of the original kitchen opened near this well which, of course, has been filled in. This door was well grooved by claw scratches, evidently made by a large dog signaling to be let in from the cold. The door was removed and is carefully preserved in the attic together with the original hardware.

A two-story ell to the back was later removed and replaced by a frame addition, also two stories high. This frame ell consisted of a dining room and kitchen below and a bedroom and large bathroom above. It had a double chimney and the stove could be used in all four rooms. The upper rooms were reached by the central hall stairway with a four-step flight from the landing into a hall from which access was obtained to the bedroom and bathroom.

Old Cider Mill, Krut Farm, Daugherty Township, Beaver County, Pa.

By Vivian Cleis McLaughlin, a former neighbor and friend.

Milestones Vol 9 No 4–Fall 1984

Daugherty Township achieved its township status by a mere four votes in 1893. It was originally part of Sewickley Twp. The land which includes present Daugherty Twp., became part of New Sewickley in 1801 and then included Pulaski in 1854.

Krut Farmhouse

One of several farms in Daugherty Twp. is the Krut Farm, purchased by Anton Krut in July of 1857, from Jesse Dean and his wife Tabitha. Mr. Dean had bought the farm from Adam Bright and his wife Eliza. The farm then was in Sewickley Twp. then Pulaski Twp. Census records list Mr. Dean as a river boat pilot in Allegheny County. According to relatives of Mr. Dean the farm was bought for speculation. The farm complete with house, barn and six out buildings and 86 acres of land was purchased by Mr. Krut for $3,000.

Anton Krut was born at Neider Schafersheim, Alsace-Lorraine in 1830. He came to Pittsburgh, Allegheny County in 1849 and pursued his trade as wagon maker. Anton married Theresa Muller in 1855. They had the following children: Philip, John, George, Joseph, Henry, Anthony, (who was a florist in Butler, Pa.) Albert (an engineer), Charles (in charge of the farm), Theresa, Mary and Rose. In 1854 he went into business for himself at Tunnel and Forbes Streets. Here he continued for five years then moved to South Fourteenth Street where he and his son, John A. ran the business until his death. Mr. Krut died April 5,1903 at the age of 73. He is survived by his children and wife who died Dec. 13, 1904. Both are buried in the Daugherty Cemetery in Daugherty Township, New Brighton.

According to Anton’s will he left his business to his son John. Mr. Krut bought the farm to provide a good atmosphere for his growing family. Eventually the farm provided employment for them all.

Charles Krut was in charge of the farm. This is the period of time that I remember along with the operation of the Cider Mill.

Searching back and talking with the grandchildren. Grace Miller Reskovic, Dorothy Majors Fischer, and Frances Majors Kolb, I discovered this farm was more than an ordinary farm. The barn contained a planning mill, cider mill, wagon shed, stalls, cows grain bins and the usual found in most barns.

This barn was unusually large. The outbuildings on the farm consisted of a summer kitchen, spring house, storage house of vinegar vats, smoke house, blacksmith shop and chicken house.

The planning mill was used to plane lumber for the wagon works in Pittsburgh. The cider mill, used to make cider, which in turn was stored to ferment into vinegar. Then vinegar was wholesaled to clients as far away as Pittsburgh and Ohio. When the Pennsylvania pure food and drug act came into effect and inspections were made, Mr. Krut did not want to update his equipment or get into bottling, so he sold the vinegar clients.

The cider mill was then opened to the public. Every fall this was a very busy place for the local farmers to go to get their apples pressed for their own supply of cider and vinegar. Horses with their wagon loads of apples would line the roadway early in the mornings, everyone vieing for an early spot in line. As time went on and apples were ground you did not know whose apples were being ground. The farmers that used the juice for their own consumption of course wanted the best. Those who sold the cider and vinegar used a second grade of apples that were not very appealing to the late comers. The cider mill operated three days a week. It had to shut down then to dry the straining cloths. I remember those huge brown cloths drying on the clotheslines.

There was also a blacksmith shop on the farm. This was used to handle the iron work that went into the wagon manufacturing. The Krut’s did a lot of truck gardening and kept cows for their own milk supply, chickens for the eggs and meat. Pigs were fattened for the fall butchering.

I remember this was the depression days but there was never a shortage of food among the farmers and neighbors. Everyone shared their wealth of food. Money was scarce but there was plenty of food.

Charles Krut and his wife Mary Catherine (Myers) Krut had the following children: Marcella Krut, Mrs. Harry Miller, Mrs. Herbert Majors, and Carl H. Charles Krut passed away in 1928 and left the farm in charge of Mr. and Mrs. Harry Miller. his daughter and son-in-law. They ran the farm until their retirement when the farm was sold.

The barn and cider mill was torn down and the slate roof and barn siding sold strictly for mercenary reasons. The Krut family was a very affluent and respected family and an asset to Allegheny, Beaver, and Butler Counties where they contributed to the economic and commercial growth and development. Many 4th and 5th generations of the Krut family still reside locally and are very proud of their heritage!

Farming Life on the Southside – 1900-1920

By Donald Bryan Smith

Milestones Vol 9 No 2–Spring 1984

The sense of history, most intimately, is the personal discovery of the reality and concreteness of change. To understand even a little of what was is a privilege, one long cherished: “Let us now praise famous men and our fathers who begat us.” More than most, I have had that privilege.

My father was born in 1897 in the “Southside” of Beaver County, Pennsylvania. Living in a rural area within thirty miles of the great coal and steel center of Pittsburgh, he felt, if indirectly, the impact of industrialization and urbanization on his community and the agricultural life which was its rationale. The changes that came were perhaps inevitable and he wouldn’t want them reversed, yet his memories of that other America are strong and good. Of course, they center on the farm.

The Smith farm which he remembers was 140 acres of rich land, of which 120 acres were arable and pasture, only 20 acres in woodlots. This farm was his father’s share of the original 400 acre purchase made by his great-grandfather shortly after the Revolutionary War, a part in turn of a much larger grant made to a hero of the Pennsylvania war effort, General Muhlenberg; it was called Paradise. My grandfather proudly claimed it was one of the best farms in the area yet, as we’ll see, the yield he derived from it was always a little short of its potential.

Although the farm’s dozen cows were a valuable asset, dairying was not its economic backbone. It was a “general farm”, with butter, not milk, the main dairy product and the rest of its output raining over eggs, wool, lambs (for mutton) and poultry. The latter were especially versatile; about 100 eggs yearly weren’t sold but hatched the hens went toward replenishing stock, the roosters to slaughter. A half-dozen hogs were also kept, to meet the same fate in the fall as the roosters, the brood sow excepted. Before the internal combustion engine solved forever the problem of propulsion, horses furnished most of the non-human energy needed for farming. and 5 or 6 of these were always to be found in the Smith barn.

Fields of corn, oats and wheat covered most of the land but these grains weren’t grown as cash crops. Ground by a neighboring miller and mixed in varying proportions, the result was fodder for the horses and cattle known as “chop”. Clover hay comprised another important addition to the animals’ diet; in good years a surplus of hay was usually produced, baled and sold at $20 per ton. Hay was also valuable in aiding the animals to produce manure. which was supplemented by phosphate and lime as fertilizers.

Corn, oats, wheat and hay were grown as part of a characteristic rotation, as follows: a field of 12 to 15 acres, which had lain in pasture for a few years would be plowed in the spring and sown with corn, which was harvested in September-cut, shocked, husked and cribbed as swiftly as other duties would allow. This field was then allowed to lie fallow until the next spring when it was prepared and sown with oats. At the same time, another sod field was being planted with corn, as the first phase of the cycle to be repeated on another section of the farm. Oats were harvested in July or August and by September the third crop, winter wheat, had been sown. The grain drill which planted wheat also sowed timothy and grass seed. By the next spring, clover was also growing in this field, having been broadcast by my grandfather on the surface of what he hoped was the last snow of the year. The winter wheat harvest took place in July and for the next four years clover and timothy held sway in the field, the former dominant at first, the latter during the third and fourth years. After the fourth year, the field was allowed to run to grass again and a few years later the cycle commenced once more with corn.

My grandfather used most of the common farm machines of the day: the aforementioned grain drill (a rectangular box on wheels, from which seeds dropped into their furrows through a series of 8 or 10 hoses), a binder for oats and wheat, and a mower and rake for hay, as well as a plow and harrow. Oats and wheat were “thrashed” by machine but since it was a task completed in only a few days, most farmers depended on a few of the more enterprising of their number, who possessed them and hired them out during the season. Thrashing was the most unpleasant of all jobs on the farm. Ten or twelve men worked steadily inside a barn where the temperature often rose above 100 degrees, forking wheat and oats into the noisy steam threshing machine and gathering the straw which was a by-product of the threshing process. The clouds of dust raised were difficult to contend with but if rust had struck the oats, an especially vile smoke rose which, when inhaled -in quantity, usually nauseated the workers. Harvesting, by comparison, was enjoyable; the heroic but exceedingly strenuous days of cradle and scythe were at least a generation in the past. Corn was still cut by hand, though, with long, machete-like knives.

As I’ve indicated, most of the grain crops were used as forage. My father’s family actually derived a much larger direct income from their garden, where potatoes, lettuce. onions, tomatoes and peas were grown. This aspect of general farmer probably loomed larger in his life than any other, for the kitchen garden became his special responsibility very early and hoeing, weeding and gathering there constituted the major part of his chores. Twice a week for ten years, until he finally left the farm in 1920, he delivered vegetables, butter and eggs to customers in Aliquippa, a booming steel town about 12 miles from the farm. Many times during these years, he and his brother rose at 5 in the morning, loaded their wagon with produce and drove into town. They were usually sold out by noon and could relax for a few hours, with dinner at a restaurant and attendance at a “picture-show” the highlights of their trip, until they had to return to the farm. The prices they received weren’t unusual for the time: a bushel of potatoes brought $2, eggs sold for 25 cents a pound. Some costs seem more incredible, with the going rate for agricultural labor one dollar per 10 hour day.

In retrospect, my father recognizes that operations which concentrate on dairying are usually more profitable but maintains that conditions in the Southside during his youth were more conductive to general farming. Not until better country roads were constructed and farmers with bulk tanks could depend on the milk companies to send trucks out for the milk would the general farm lose ground to the dairy. Another advantage of the former was that it made a near self-sufficiency in regard to food. There were always plenty of fruit and vegetables, milk, butter and eggs; bread was home-made from their own wheat flour, and meat, in the form of poultry and pork was in adequate supply. Only coffee, sugar and spices had t be imported.

A farm family harvesting the apple crop.

Other necessities of life were also derived from the farm or nearby. Two springs provided abundant water for both the stock and their owners but plumbing, after an unsuccessful attempt by my grandfather to pipe a supply into the kitchen. was nonexistent. A washhouse for sanitary purposes year-round. These were constructed from timber originally cut in the woodlot and turned into lumber by the Kennedy sawmill. The Smith home was heated by coal, also supplied by the enterprising Kennedy family who worked a small-scale mine. These were extremely numerous in western Pennsylvania and known as “coal banks”, rendered coal almost literally dirt cheap in this region. My grandfather bought 10 tons, enough to last the winter, at $2 a ton. Virtually anything which couldn’t be wrung from farm industry-clothing, shoes, tools could be purchased from Sears and Roebuck, whose “wish book” also gave a farm family access to a few modest luxuries.

Schooling for farm children was much more casual at the turn of the century than it is now. The full school year was only 7 months. from the first of September to the first of April and attendance was not compulsory. My Uncle Donald, several years older than my father and capable of doing a man’s work at 14, often didn’t start school until October and usually left in March, enabling him to give moret ime to farm-work. More rule than exception, this largely accounts for the presence of fairly intelligent 17 year olds, in the class room with children 10 years younger, still trying to complete their sixth grade of grammar school education (the Smith School, which was located on what had been Smith land when it was built, was a traditional one-room school). Very few children managed those six grades in as many years; my father, kept from starting until he was 7 by illness didn’t graduate until he was 15.

The curriculum was rudimentary: the 3 R’s plus some history, geography and physiology. The teachers were hardly qualified to handle anything more ambitious (my father doesn’t remember if they were required to have even a high-school diploma; certainly nothing more). Paid $40 to $50 a month only during the school year, this largely male group of young people survived only because most of them came from farm families too and lived at home. Given this “training”, the quality of their teaching was surpisingly high. What comes as more of a shock to a present-day student is the complete lack of institutionalized guidance offered: rural education, at least, was strongly laissez-faire and an ambitious student who wanted more learning had to work things out for himself. Not surprisingly, my father estimates that of the approximately 50 classmates he had, only a dozen went on to enter professions. Only at age 20, after determining on his vocation in the ministry, did he return to high school and, later, himself taught school to earn money for college.

The school had no money to waste on extra-curricular activities, either, unless ball-playing at recess and attending a spelling bee at the Crab Hollow school could be so classified. There were no athletic or music programs, again, as in the stereotype of rural life, people had to fend for themselves, to create their own entertainment and recreation. Unlike the pessimistic stereotype, the speaks of a relatively full social and cultural life. Perhaps time hung less heavy on his hands because of his passionate love of reading: although he didn’t see the inside of a library until college, he managed to get his hands on a fair amount of books during his years on the farm and recalls that the first money he ever earned was spent on a subscription to the “Youth’s Companion”, the title of which accurately indicates its contents and from which he gained pleasure and inspiration that he’s still grateful for. In a world unaquainted with radio, television or the stereo (he heard his first recorded music on a neighbor’s phonograph), this companion was indeed a cherished one.

One institution which gave young people an opportunity for public recognition while bringing rural families together was the literary society. My Aunt Bertha was evidently a gifted speaker whose rendition of “Kentucky Belle” was particularly admired. The society also staged plays but, like many ventures depending on the energy and talent of a relatively few people. declined in importance as my father grew older. A revitalized Grange helped to fill the consequent cuItural gap after 1912 and Farmer’s Institutes, which were annual occurrences at Service Church, presented speakers from the State Colleges as well as lighter entertainment. Country dances at Uncle John Smith’s were widely known and well attended. The Kennedy’s , exhibiting another facet of their versatile natures, had formed a family band and provided the music for most of these affairs. Neither the Beaver County Fair at New Brighton nor the more accessible Hookstown Fair played a very large part in the lives of my father and his family; they never exhibited stock and attended only the latter.

The community of the Southside at its widest never really embraced the new urban centers of Aliquippa and Midland. Certainly, there were economic ties between city and country and a dynamic relationship which was relentlessly depopulating the country, but the Southside was an overwhelmingly rural entity, subdivided into townships, school districts and church parishes. Within the narrower society of Raccoon Township and the Service Church congregation, my father perceived his family as prosperously average within a narrow range of welfare which had no place for extreme wealth or poverty. My grandfather -could never hope to leave an estate including a $50,000 bank account like Will Thorne did but he’d never have to worry about his sons having to become hired men either. Real poverty may have been well disguised or studiously ignored. It may be that, at least fora limited period, there really was a safety-valve in operation in Beaver County; there was an endless demand for labor in the towns I’ve already mentioned.

Of course, even the most fortunate inhabitants of the Southside accepted without question deprivations which seem quite shocking. There was no such thing as continuous medical care; a doctor was called in only when someone was seriously ill, and often not then. For years, the whole area was dependent on two physicians, old Dr. Shane and young Dr. Ewing, who had to shoulder an increasing burden as the years went by and literally worked himself to death, jouncing on the dusty or muddy, rutted country roads from crisis to crisis. Two of my father’s siblings died in infancy and there were many families similarly afflicted; Service Church cemetary was. he said, “awfully full of little gravestones.” Diptheria was the great killer of children, typhoid of adults while smallpox was no longer the scourge it had once been, though pock-marked faces were not uncommon.

It doesn’t require great insight to recognize that this was a society whose consumption of material goods (no indoor plumbing. electricity, rapid private transportation) and services (limited educational opportunity, minimal health care and mass entertainment) was at a much lower level than ours. Less obvious but of equal importance was its limited consumption of information, its detachment from what we now consider to have been the main currents of history in the early 20th century. Rural isolation, in this context. doesn’t seem to apply to a situation within the community but describes the relation of the community to the “outside” world.

The Southside, always excepting its urban centers was overwhelmingly white Anglo-Saxon Protestant in ethnic and religious character and Republican by political preference. The pattern of general farming seems to have cushioned the impact of market and railroad, rendering Populism less appealing. Although our family boasts of a distant kinship with William Jennings Bryan, my grandfather voted for McKinley in 1890 all the same. One of my father’s first memories, in fact, was of the shock which his assassination caused and how well a cheap memorial biography sold when it was hawked from home to home by a neighbor boy. It’s not surprising that a people who had to depend on the weekly Beaver Falls Review for news would be largely unaware of epochal scientific discoveries or the progress or decadence of modern art but when I was informed that Teddy Roosevelt figured most prominently not as a trustbuster or statesman but as an advocate of large families, I was a little incredulous. Progressivism was largely an urban phenomenon; when Progressives did have something to offer country dwellers, they found responsive citizens, as did Gifford Pinchot when, he promised, if elected governor, to “get the farmer out of the mud” by paving the roads.

Farmers are naturally ambivalent in their reactions to the contention of capital and labor. Often feeling oppressed by the former and a kinship with the latter because of a perception of common productive effort, they are also employers and men ‘of property themselves. On the Southside, I think this ambivalence was rather negatively formulated as a “plague o’ both your houses” attitude. My father’s youth was spent during a lull in the intensity of labor activity in western Pennsylvania. The steel workers had been broken for a generation by Carnegie and Frick in the 1890’s and the Smiths, least of all people, would have been affected by the great anthracite strike of 1902. There were irreverent remarks about the idle rich and Rockefeller and Vanderbilt (or even Carnegie) were not names which evoked awesome respect but there was no great dissatisfaction with the status quo. Indeed, there may have been something of a consensus that things were organized rather well. In the summers of 1907, 1908 and 1909, the Standard Oil Company ran three 6-inch pipelines on their way from Oklahoma to Pittsburgh through my grandfather’s fields. He appreciated this windfall, of course, but my father enjoyed more deeply watching the somewhat exotic Italian laborers digging ditches, followed by the arrival of the popes and their assembly and laying by largely American “tong gangs” (the machine used in screwing pipes together resembled giant tongs). Even after the pipes were safely buried, potential leaks caused Standard Oil to hire a man to walk the 36 miles from the Ohio border to the line’s terminus near Pittsburgh and back once a week to report on its status. This pipeline walker was a guest at the Smith house every Wednesday for many years thereafter.

The Southside could easily ignore the events in Europe which were leading to war; my grandfather was optimistic and told his son, as late as 1912, that there would be no more wars. When March, 1917 arrived, however, there was no protest over American’s entry into the war. American opinion had become so belligerent that the few Germans in the area, my father recalls disapprovingly, were given an extremely hard time. What more thoughtful Southsiders had noticed for years was the growing number of abandoned farms. Farm families had diminished in size since the 1850’s and the 1860’s. as machinery reduced the amount of human energy that had to be expended. But a man still needed 2 or 3 sons to help him out; rom the end of the 1890’s, more and more farm boys were leaving for the towns, for all the immemorial reasons. Left without this unpaid labor, most farmers couldn’t afford to continue; they sold what they could, but there were always more sellers than buyers. Savings were usually modest and in some cases, while a farm which had been cultivated for a century stood idle, its owner worked as a hired man a few hundred yards away. Membership shrank so much at Service Church that it was forced to share its minister with another congregation. Yet, the loss in attendance was only in absolute terms; relative to the smaller population it remained the same. By this measure, the community was in decline, but not disintegrating.

Farming life was satisfying to my father-hard work but plenty to eat and enough to wear, though the cash return was small. With deep sympathy, he sees his father as a man who struggled against his own frailty, the loss of his beloved wife at a sadly early age and a succession of small misfortunes, all of which kept him from making as much of the farm as could have been. In the 1920’s, cultivation of the Smith farm was no longer practical as my father left for college to follow an ideal that couldn’t be confined to the Southside and my uncle to fulfill his own family responsibilities. During the experiment with Prohibition, moonshiners from Pittsburgh took advantage of the many empty farms by renting them, for the professed purpose of pasturing cattle; behind this protective facade; illegal stills were set up and operated. My grandfather was hood-winked in this manner by a “butcher” from the city.

The homogenization of American culture accelerated in the 1920’s and succeeding decades, leaving the Southside merely the southern half of Beaver County. The rural areas are being peopled more heavily now than they ever were, but the farming life my father knew can never return. Very few even of those who lived it would wish it to and I’ve attempted to avoid historical sentimentalism. All I wanted to do was help to preserve and understand a man’s memories of a different and lost existence which is part of our past.

The substance of this paper is largely derived from several conversations with my father, the Rev. Harold C. Smith on May 7 and 8, 1975. The interpretations blend of his opinions and mine, with some reliance on widely accepted generalizations.

You must be logged in to post a comment.