Public History Matters

Carrying Our History Forward

The Klan’s Living Legacy

The Legacy Years

We are trying to understand the history and legacy of the Ku Klux Klan in Beaver County, Pennsylvania, especially after its organizational heyday in the 1920s.

Local organizations (Klaverns) may have disbanded after the 1920s, but the Klan’s fundamental ideology, values, and attitudes toward society, race, immigration, religion, patriotism, and many other issues are living on, simmering in what we call the legacy years.

In this sense, we would argue, the Klan’s original extremist worldview survives to this day in Beaver County, albeit evolved in response to the social, economic, and political conditions of our time. We have not seen hooded rallies, yet, but we have seen renewed expressions promoting well-documented Klan sentiments–as the parade banner above illustrates: America first, one God, one country, and one flag. Like in the 1920s, contemporary messaging champions anti-socialism, freedom from government tyranny, individual liberty, and gun rights.

Today, the rhetoric of like-minded affinity groups, social movements, and propaganda factions of the media is not far removed from the way in which the Klan defined itself in terms of extreme nationalism, racial animus and bigotry, cultural grievances, and hyper-patriotism.

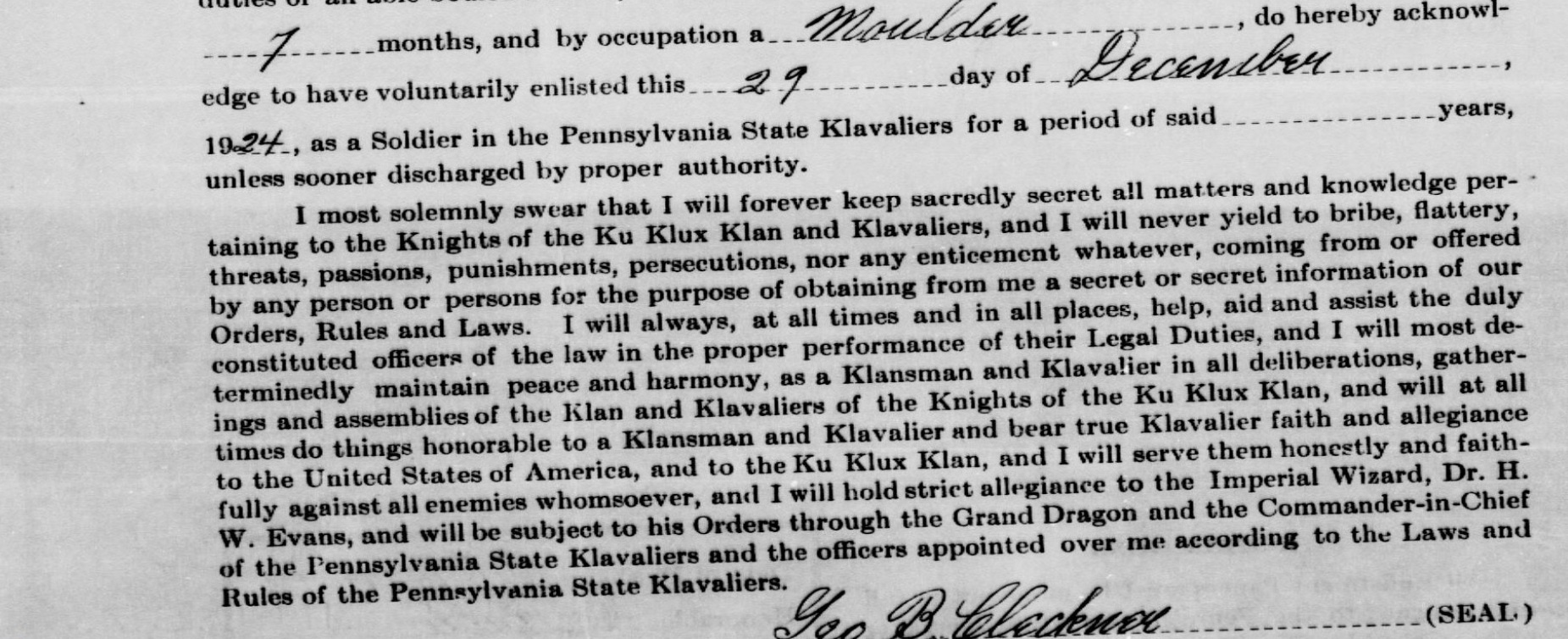

Perhaps the most troublesome trait among these groups and movements–historically and today–is the dubious claim to be peaceful and non-violent, except “against all enemies whomsoever,” as the Pennsylvania State Klavaliers oath declares. (See New Brighton’s George B. Cleckner’s original Pennsylvania State Klavaliers Enlistment Paper).

All Enemies Whomsoever

In recent times we’ve also witnessed certain affinity groups declare profound respect for law enforcement. The term in contemporary use is, “Backing the Blue.” In 1924, the Klan declared that they, too, would “in all times, in all places, help, aid and assist the duly constituted officers of the law in the proper performances of their Legal Duties.”

However, we’ve been reminded that such bloviated reverence for law enforcement can be tenuous–some would say disingenuous. For example, some President Trump supporters on the steps of the US Capitol during the January 6, 2021 insurrection demanded to know if law enforcement officers there were either with them or against them, setting into motion a wave of violence against Capitol police officers the crowd viewed as enemies of their cause (i.e., to “stop the steal” of the 2020 presidential election).

Despite overt declarations of being pro law enforcement, contemporary Klan affinity groups such as the Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers rationalized their violence against Capitol police because they were perceived as enemies of their cause–a peculiar like-minded notion also found in the Klavaliers Oath of the 1920s.

Defining Americanism

We contended that since the 1920s (an era known as the Klan’s second coming) we still carry with us a certain heritage of ideals, beliefs, and attitudes that continue to frame social, economic, and political issues. As historian Peter Amann writes in Vigilante Fascism, “Even though the collapse of the second Ku Klux Klan by the mid-1920s undoubtedly left organized nativism in one of its periodic troughs, there is no reason to suppose that the attitudes and resentments on which the Klan had fed had suddenly vanished” (Amann 2009, note 2).

The scope of impact on mainstream America during the 20s is remarkable, and the Klan’s activism was felt widely. It helped shaped the Immigration Act of 1924 reducing Jewish immigration and nearly stopping Asian immigration completely. It influenced eugenics-minded laws in thirty states that permitted forced sterilization disproportionately among African American women and other minorities. The Klan successfully created a national movement forcing school boards to remove textbooks that speak unfavorably about our nation’s Founders. Moreover, the Klan was instrumental in reshaping our notion of patriotism.

Journalist Eric Herschthal writes, to the Klan “Defending the rights of immigrants or black people made you a sell-out. Meanwhile, fairly common symbols of patriotism, like honoring veterans and respecting the flag, took on unmistakably racist overtones. You could not critique the government’s military policy or refuse to sing the national anthem without being seen as “un-American” (Herschthal 2018).

The Socialist Un-American Threat of Organized Labor

Organized labor is a topic near and dear to many Beaver Countians. Generally, unionism has been championed here, especially during and after the war years. But the Klan was typically anti-union in the earliest days of organized labor, and it brought to bear its peculiar notion of Americanism upon the movement. Unions were not patriotic.

“Supporting unions made you a shill for socialism,” Herschthal reminds us. And in the 1930s this attitude resonated with many in Beaver Countians who felt threatened by a radical, foreigner-inspired Congress of Industrial Organizations trying to organize the steel industry and upset the status quo power structure. Again, such actions were viewed as unlawful, unpatriotic, and un-American by many nativist groups carrying on the Klan’s legacy.

To best understand how this played out in Beaver County, it worth quoting Kenneth Casebeer from his article, “Aliquippa: The Company Town and Contested Power in the Construction of Law:”

“Workers were fired especially for attempts at economic self-organization. If there was perceived to be a difference in these posed threats, unionism was the highest sin. Pete Muselin, born in Croatia, arrived in America in 1912, and reported being threatened and arrested numerous times for attempting to hold an organizing meeting. He was told that,

‘[w]e make the rules. This is not the United States. This is Woodlawn, and we’re going to do what we please because J & L gives bread and butter to all these people. . . . Every once in a while the cops came to my home and just raided the place – no warrant, no nothing. They would take every book, every periodical, every bulletin; they’d just dump them in a pile and throw them in the police cruiser and they would never return them. They were looking for books on Marxism, but they could not distinguish one book from another, in order to make sure they cleaned out the house.’

“While he was [Aliquippa] chief of police, Mike Kane would run his motorcycle right into a boarding house kitchen to break up the ‘Hunkies.’ In Aliquippa, attempting to organize a union was punishable by five years in prison” (Casebeer 1995, 634-635).

In 1934 the anti-union strife extended to Ambridge. “Sheriff O’Laughlin, chief law enforcement official in Beaver County and formerly head of the Jones & Laughlin Coal and Iron Police, was, in his words, contacted by all the industrial plants demanding protection and offering to pay all expenses of special deputies. Where upon, he got William Shaffer, commander of the American Legion Post in Aliquippa, to provide seventy-five boys with military experience, and added another seventy-five by his own efforts. In all 248 special deputies were sworn in, of which about fifty were J & L employees. The steel companies eventually paid $24,811.40. The men were transported to Ambridge, organized into squads of four with at least one ex-serviceman, given weapons, and placed under the command of four lieutenants.

“One of these was Mike Kane, who was at that time justice of the peace in Aliquippa and an employee of J & L. The force was accompanied by Burgess (mayor) Caul of Ambridge and the county’s prosecuting attorney. They marched military style to the Spang-Chalfant plant on Twentythird Street, carrying tear gas, shotguns, clubs, revolvers and machine guns, marked with white handkerchief arm bands and some wearing overseas helmets” (Casebeer 1995, 638-639).

The involvement of the American Legion, a veterans organization, is particularly interesting, as it underscores the Klan’s long-standing practice of infusing militaristic patriotism and its own concocted definition of Americanism into every cause and grievance.

In “It Can’t Happen Here: Fascism and Right-Wing Extremism in Pennsylvania, 1933-1942,” historian Philip Jenkins writes, “In Pennsylvania the Legion was both active and militant, and in 1930 there were 73,000 members organized in 567 posts. In 1927 its role as self-appointed guardian of ‘Americanism.”

“It was in the realm of industrial organization that the Legion attracted its greatest notoriety. The group was especially powerful in the southwest of the state, in the steel and coal regions. These were also the old Klan centers and there was considerable overlap of membership. The Legion here provided the footsoldiers for opposition to the Steel Workers Organizing Committee, SWOC, the predecessor to the CIO. In 1933, Aliquippa police chief Michael Kane led two hundred armed men, mainly Legionnaires, against steel strikers in the town of Ambridge, resulting in the death of one man and the gassing or wounding of hundreds of others. In 1935, Kane reappeared as the leader of a new organization called the Constitutional Defense League, described as an offshoot of the Legion’s “National Americanism Commission.” Kane himself urged that union organizers be hanged or “taken for a ride” (Jenkins 1995, 38).

It’s important to note that in Beaver County history, references to the Klan are hard to find outside of the 1920s. Locally, formally chartered Klaverns in Ellwood, Rochester (“Junction City Klan”), Ambridge, Beaver, Ohioville (“Midland Klan”), Sewickley, and East Liverpool (“Columbiana County Klan”) went out of business, so to speak. But the 1930s—and beyond—substantiates Peter Amann’s claim that the Klan’s world view and ideology (e.g., attitudes toward patriotism, law and order, vigilantism, as well as grievances toward race, immigration, and organized labor) didn’t suddenly vanish.

In some respects, the Klan never left Beaver County. But we’ll never fully understand this as long as public historians dare not move past treating local history as an uncritical cute game of trivial pursuit and atheoretical waltz through nostalgia-land. Some history is simply unsettling, and we should embrace that truth.

REFERENCES

Amann, Peter H. Vigilante Fascism: The Black Legion as an American Hybrid. Cambridge University Press. June 3, 2009.

Herschthal, Eric. “The KKK’s Attempt to Define America: Two new books explain how the Klan gained so much power in the 1920s.” New Republic. January 16, 2018. Accessed November 24, 2021. https://newrepublic.com/article/146616/kkks-attempt-define-america

Casebeer, Kenneth M. 1995. “Aliquippa: The Company Town and Contested Power in the Construction of Law.” Buffalo Law Review 43, no. 3 (Winter): 634-635.

Jenkins, Philip. 1995. “It Can’t Happen Here”: Fascism and Right-Wing Extremism in Pennsylvania, 1933-1942.” Pennsylvania History 62, no. 1 (January): 38.

Beaver Countians Enthusiastic About National Touring Rally

In what could be described as an entertaining exaltation of contemporary hot-button political, social, cultural, and economic issues, Beaver Countians generously attended the nationally promoted, “Arise USA Resurrection Tour” rally held on July 21, 2021 at McIntosh Park, Beaver.

Displaying theatrics reminiscent of Klan rallies of the 1920s–which were often festive affairs–this event was steeped in hyperbolic patriotism, religiosity, and political grievances. Fundamentally, the rally served as a mobilizing mechanism meant to agitate and galvanize the audience with topics such as COVID-19 restrictions, election fraud, satanic pedophilia, and critical race theory.

Officially, the rally was organized around key concepts of “faith, family, and freedom,” as well as something called “constitutional counties.”

“We are going to be loud, we are going to be bold, and we are not going to stop until we get what we want,” declared Jamie Sheffield at the rally, co-founder of Audit the Vote PA, a group that insists, without evidence, that the 2020 presidential election was fraudulent and stolen from Donald Trump.

At the rally, Beaver County Sherrif Tony Guy praised the work of Audit the Vote PA. “What a tremendous job they’re doing!” he said.

“All constitutional sheriffs, they got a place in heaven as well, and we’ve got one here in Beaver County, Pennsylvania,” proclaimed the emcee calling Guy to the stage. The sheriff, adorned with gun and badge on full display, went on to proclaim the virtues of faith, family, and freedom. Specifically he asked the audience to pray, support local businesses, appreciate law enforcement, and support Republican candidates.

As a so-called “constitutional sheriff,” Guy enjoins himself with the “constitutional county movement” and the growing belief that sheriffs are the highest local law enforcement officials and they have the authority, power, and duty to defy or disregard laws they view as unconstitutional.

It would be unfair to characterize Sheriff Guy as a modern-day Mike Kane, but Guy’s conflation of his legal duties, politics, and cultural mores is consistent with the way in which Klan-era law enforcement officers defined their own power and wrapped themselves in nationalist, right-leaning ideologies popular in their day.

Gallery with alias: PUBLIC_HISTORY_BLOG_POSTS not found

PUBLIC HISTORY MATTERS

At The Social Voice Project, we celebrate history and people through our community oral history projects that give us a chance to look, listen, and record the voices and stories of our time. We encourage all local historical societies and museums to capture, preserve, and share their communities’ lived experiences, memories, customs, and values. Future generations are depending on it.

Contact TSVP to learn more about our commitment to public history and technical assistance in creating community oral history projects.

MORE ESSAYS & THOUGHTS ON PUBLIC HISTORY

You must be logged in to post a comment.