Plagiarism: Ripping off Local Historians and History

Image: Inernational Journal of Research webpage: “Plagiarism” (August 20, 2020)

What Plagiarism Looks Like

It's a Serious Problem

“The expropriation of another author’s work, and the presentation of it as one’s own, constitutes plagiarism and is a serious violation of the ethics of scholarship,” concludes the American Historical Association. “It seriously undermines the credibility of the plagiarist, and can do irreparable harm to a historian’s career.”

The concept is simple enough: if you’re an historian you ought not steal from other people’s creative work or creations. Don’t rob another organizations’ archives and pass artifacts off as your own. Don’t steel other people’s historical writings and claim them to be your own words and ideas. But if you do borrow from other sources, at least give credit or attribution to the source preferably using an acceptable method such as the Chicago Manual of Style.

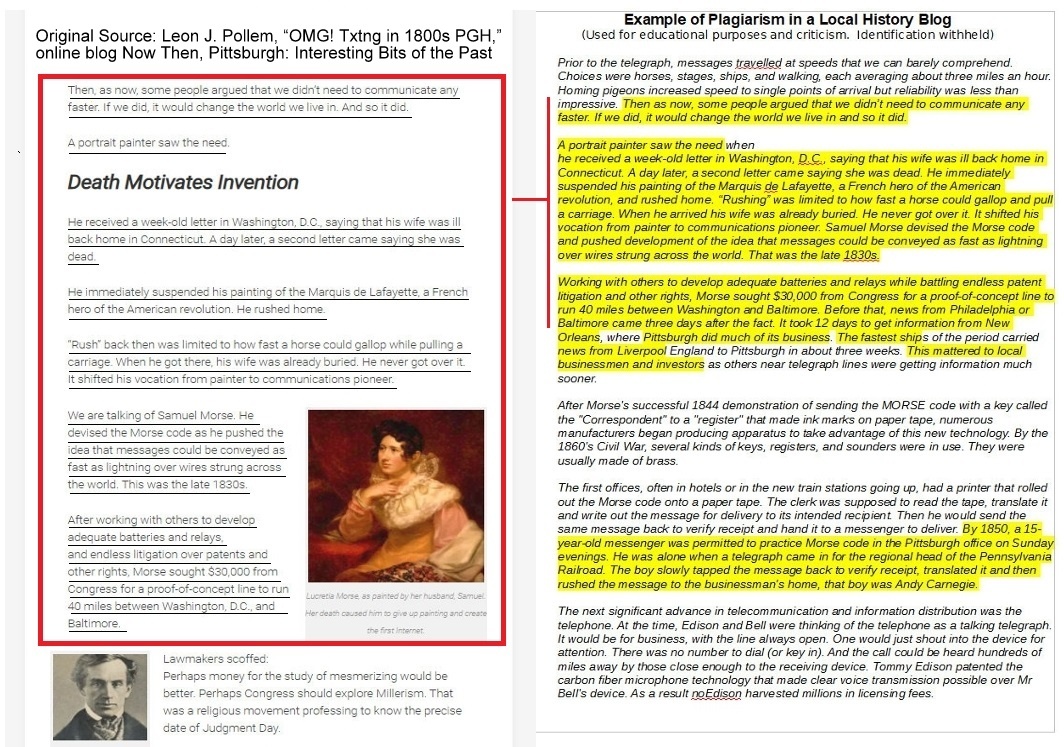

So what does plagiarism look like? Above on the right is an example taken from an social media-based local history blog. Highlighted in yellow is text–nearly word for word expropriated (aka stolen) from a published work on the left by Leon J. Pollem (“OMG! Txtng in 1800s PGH,” appearing in Now Then, Pittsburgh: Interesting Bits of the Past [November 13, 2018]). Maybe the local history blogger had permission to use the text? There still needs to be a citation or attribution. Maybe the text is paraphrased? It still needs a reference of some sort. The lack of quotation marks suggests that these words belong to the local history blogger, but they do not. A Google text search identified these exact words and paragraphs as belonging to Mr. Pollom. Here is the original source; judge for yourself.

Obviously this appears to be blatant plagiarism. But so what? Who cares? Great questions. Next to this blog post you can read the American Historical Association’s official statement about plagiarism. It’s an easy read, but moreover it will put this issue into wider context and you’ll understand why stealing someone else’s intellectual property and passing it off as your own is downright unacceptable.

Ethical Standards for Historians

American Historical Association

Statement on Plagiarism

The word plagiarism derives from Latin roots: plagiarius, an abductor, and plagiare, to steal. The expropriation of another author’s work, and the presentation of it as one’s own, constitutes plagiarism and is a serious violation of the ethics of scholarship. It seriously undermines the credibility of the plagiarist, and can do irreparable harm to a historian’s career.

In addition to the harm that plagiarism does to the pursuit of truth, it can also be an offense against the literary rights of the original author and the property rights of the copyright owner. Detection can therefore result not only in sanctions (such as dismissal from a graduate program, denial of promotion, or termination of employment) but in legal action as well. As a practical matter, plagiarism between scholars rarely goes to court, in part because legal concepts, such as infringement of copyright, are narrower than ethical standards that guide professional conduct. The real penalty for plagiarism is the abhorrence of the community of scholars.

Plagiarism includes more subtle abuses than simply expropriating the exact wording of another author without attribution. Plagiarism can also include the limited borrowing, without sufficient attribution, of another person’s distinctive and significant research findings or interpretations. Of course, historical knowledge is cumulative, and thus in some contexts—such as textbooks, encyclopedia articles, broad syntheses, and certain forms of public presentation—the form of attribution, and the permissible extent of dependence on prior scholarship, citation, and other forms of attribution will differ from what is expected in more limited monographs. As knowledge is disseminated to a wide public, it loses some of its personal reference. What belongs to whom becomes less distinct. But even in textbooks a historian should acknowledge the sources of recent or distinctive findings and interpretations, those not yet a part of the common understanding of the profession. Similarly, while some forms of historical work do not lend themselves to explicit attribution (e.g., films and exhibitions), every effort should be made to give due credit to scholarship informing such work.

Plagiarism, then, takes many forms. The clearest abuse is the use of another’s language without quotation marks and citation. More subtle abuses include the appropriation of concepts, data, or notes all disguised in newly crafted sentences, or reference to a borrowed work in an early note and then extensive further use without subsequent attribution. Borrowing unexamined primary source references from a secondary work without citing that work is likewise inappropriate. All such tactics reflect an unworthy disregard for the contributions of others.

No matter what the context, the best professional practice for avoiding a charge of plagiarism is always to be explicit, thorough, and generous in acknowledging one’s intellectual debts.

All who participate in the community of inquiry, as amateurs or as professionals, as students or as established historians, have an obligation to oppose deception. This obligation bears with special weight on teachers of graduate seminars. They are critical in shaping a young historian’s perception of the ethics of scholarship. It is therefore incumbent on graduate teachers to seek opportunities for making the seminar also a workshop in scholarly integrity. After leaving graduate school, every historian will have to depend primarily on vigilant self-criticism. Throughout our lives none of us can cease to question the claims to originality that our work makes and the sort of credit it grants to others.

The first line of defense against plagiarism is the formation of work habits that protect a scholar from plagiarism. The plagiarist’s standard defense—that he or she was misled by hastily taken and imperfect notes—is plausible only in the context of a wider tolerance of shoddy work. A basic rule of good note-taking requires every researcher to distinguish scrupulously between exact quotation and paraphrase.

The second line of defense against plagiarism is organized and punitive. Every institution that includes or represents a body of scholars has an obligation to establish procedures designed to clarify and uphold their ethical standards. Every institution that employs historians bears an especially critical responsibility to maintain the integrity and reputation of its staff. This applies to government agencies, corporations, publishing firms, and public service organizations such as museums and libraries, as surely as it does to educational facilities. Usually, it is the employing institution that is expected to investigate charges of plagiarism promptly and impartially and to invoke appropriate sanctions when the charges are sustained. Penalties for scholarly misconduct should vary according to the seriousness of the offense, and the protections of due process should always apply. A persistent pattern of deception may justify public disclosure or even termination of a career; some scattered misappropriations may warrant a formal reprimand.

All historians share responsibility for defending high standards of intellectual integrity. When appraising manuscripts for publication, reviewing books, or evaluating peers for placement, promotion, and tenure, scholars must evaluate the honesty and reliability with which the historian uses primary and secondary source materials. Scholarship flourishes in an atmosphere of openness and candor, which should include the scrutiny and public discussion of academic deception.

The American Historical Association’s Statement on Standards of Professional Conduct (updated 2019) can be found here.

What Can Be Done About Plagiarism?

Stop the Steal

Public historians with little to no formal academic training in historiography and museum curation are far more likely to commit plagiarism. More generally, those with very little training in professional or academic writing are also more likely to plagiarize sources. In these cases, a bit of professional training should solve the problem.

However, a far greater concern is with public historians who simply do not care that they are plagiarizing sources. They are more likely to be acute and chronic offenders. It’s inconceivable that anyone who knowingly and egregiously commits plagiarism would stay on staff very long at any competently run museum or historical society. That’s the good news.

The bad news is that far too many of these plagiarizing public historians work independently as amateur enthusiasts. Increasingly, these plagiarists find an outlet for their work on self-created internet websites or social media pages and platforms.

On some level, the internet is very good at discovering unauthorized uses of copyrighted material. Someone who misuses sound and video content may receive a Digital Media Copyright Act (DMCA) “take down notice.” Unauthorized use of digital media is serious business, and it comes with civil and criminal consequences, especially from well resourced corporations that own the rights to digital media and other content.

But who is going to stop the small-town local historian who writes a little blog and inserts a couple of plagiarized paragraphs into his posts? Who’s going to flag a low-resolution screenshot of a published photograph or page from a copyrighted manuscript? Who’s going to call out the plagiarism?

You are, of course, dear fellow public historians. As the American Historical Association reminds us, “All historians share responsibility for defending high standards of intellectual integrity.”

Fix the Problem

Citing sources—no matter when or how it is done—is essential to the credibility and integrity of historical work.

When public historians come across plagiarism in their museums or historical societies (e.g., in museum documents and manuscripts, programming information, presentations, or online postings), the most prudent course of action is to “fix the problem.” This might mean the complete rewriting of materials when possible, or perhaps the addition of annotations and citations that give credit to the original authors or creators of source material. It’s never too late to do this.

In most cases, amending the source accuracy of historical content is quite easy with digital media, which is yet another reason public historians should be using digital media as much as possible. Editing metadata, updating electronic records, revising online content with captions and attribution, and documenting content robustly is all possible through digital media (e.g., photos, sound, film/video, and associated texts).

Fixing the accuracy of historical content on social media is extremely easy by editing posts to include proper attribution or simply removing and replacing old content with revisions.

Avoid Plagiarism

The best say to avoid plagiarism in historical work or anywhere else is not to do it in the first place. Here are some rules and best practices (Source: University of New South Wales, information used whole or in part, adapted from the web page, “Common Forms of Plagiarism”):

Caution when copying content

Don’t use the same words as the original text without acknowledging the source or without using quotation marks.

Don’t put someone else’s ideas into your own words without acknowledging the source of the ideas.

Don’t copy materials, ideas, or concepts from a book, article, report or other written document, presentation, composition, artwork, design, drawing, website, internet, other electronic resource without appropriate acknowledgment.

Quote and paraphrase appropriately

You can use the exact words of someone else (quotation) or a close approximation of those words without quotation marks (paraphrase), but both require proper credit to the source.

Don’t relying too much on other people’s material.

Don’t repeatedly use long quotations, even with quotation marks and proper citation.

Don’t piece together quotes and paraphrases into a new whole, at least not without proper credit and references to the sources.

Warning about the internet

Just because something is on the internet doesn’t mean it is in the public domain or free and clear of copyright restrictions.

Published content on the internet may be there inappropriately or illegally. Make sure you understand the full usage rights of something you are downloading or copying from the internet.

Always double check public domain and creative commons claims about content because you are ultimately responsible for the content that you create and publish.

Gallery with alias: PUBLIC_HISTORY_BLOG_POSTS not found

PUBLIC HISTORY MATTERS

At The Social Voice Project, we celebrate history and people through our community oral history projects that give us a chance to look, listen, and record the voices and stories of our time. We encourage all local historical societies and museums to capture, preserve, and share their communities’ lived experiences, memories, customs, and values. Future generations are depending on it.

Contact TSVP to learn more about our commitment to public history and technical assistance in creating community oral history projects.

MORE ESSAYS & THOUGHTS ON PUBLIC HISTORY

You must be logged in to post a comment.